Minari

By Brian Eggert |

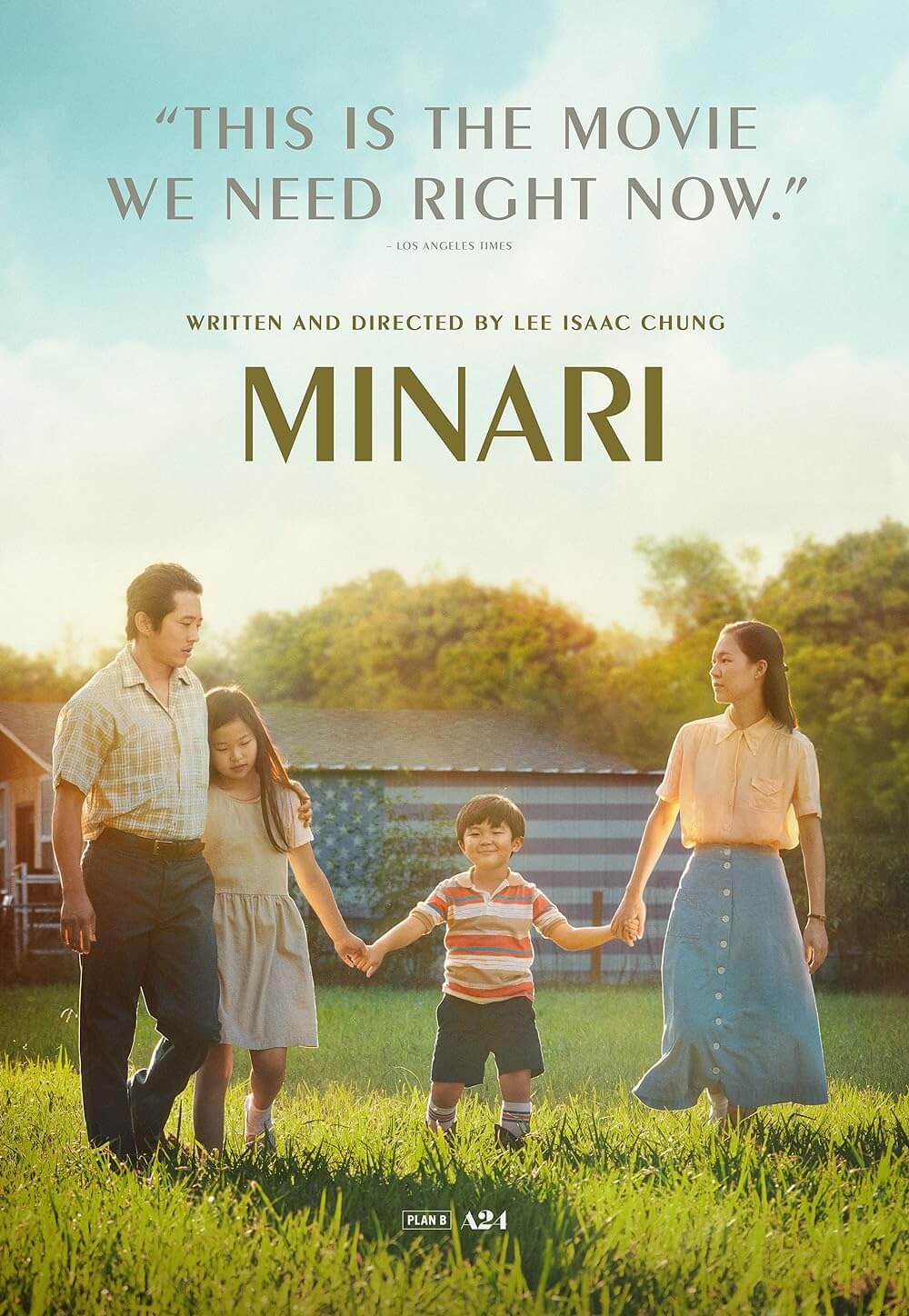

Based on Lee Isaac Chung’s real-life experiences as a boy, Minari finds its characters trying to develop a fifty-acre piece of land in Arkansas into a home and working farm. It’s a quintessentially American story in that respect, reminiscent of Westerns that follow explorers into unfamiliar territory to make a home for themselves. Although its characters move against the traditional tide, from the West to the East across the country, their story is no less archetypal. Originally from South Korea, the Yi family first settled in California. The film begins as they arrive at their new property in Arkansas. They pass through unfamiliar farmlands and soon reach a narrow passage in a forest, at the end of which resides their new home on an isolated plot. Their house, a mobile home propped up with tires and cinder blocks, hardly impresses Monica (Yeri Han), who looks at her husband in disbelief. But Jacob (Steven Yeun) reaches down into the soil and reassures her, “This is the best dirt in America.” It’s a moment that captures all the uncertainty yet determination that defines and links every immigrant story, no matter if they hail from England, Italy, Mexico, or Korea.

The story resembles others of its kind, but Minari offers details unique to the Korean experience. Jacob and Monica could have maintained a steady lifestyle in California, where they worked as chicken sexers, sorting baby chicks by gender. In Arkansas, they get jobs doing the same thing, except now they have land. It’s the early 1980s, and Jacob dreams of establishing a farm of Korean vegetables, which he plans to sell to grocers in the city. They also have two children: an adolescent girl, Anne (Noel Kate Cho), and a young boy, David (Alan S. Kim), whose heart murmur remains a constant concern for Monica. Although Jacob has the American Dream on the brain, Monica occupies herself with questions of practicality: How will they afford food? How will the children acclimate to country living? To what degree should they blend in with the local culture, and how much should they try to embrace their heritage? Should they attend a church where they will be the only non-white people in the congregation, or should they start a Korean church? These remain questions for every first-generation immigrant—it’s part of the constant struggle between one’s cultural heritage and the complex identities of generations to come.

And so, Jacob works the farm on nights and weekends along with a hired hand, Paul (Will Patton), an evangelical Christian prone to praising Jesus and speaking in tongues, much to Jacob’s chagrin. He doesn’t believe in such fanciful ideas; he prefers logic and reasoning. Take Jacob’s response to the water diviner who asks a hefty price tag to search Jacob’s land with a forked stick and identify the ideal spot for a well. He turns the huckster away and uses the moment to test David—and even the child knows that lower land near trees is a clear sign of water underneath. One Sunday, the Yi family sees Paul carrying a wooden cross on his shoulder—the Korean War vet’s way of atoning for his sins, the exact nature of which remains a secret. Jacob chuckles in amusement, though Monica, who’s more religious, thinks there’s something to Paul’s beliefs. Later in the film, after the well runs dry and the family learns that the former owner killed himself after his farm failed, Monica allows Paul to exorcise their home with holy water and jabbering prayer. The outcome seems to confirm that some measure of assimilation is necessary to thrive.

The film’s perspective regularly shifts between David and his father. The most touching and immersive scenes focus on David and his grandmother, Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung), forming a bond that proves uneasy at first. He complains that she “smells like Korea” and doesn’t do what grandmothers should, like bake cookies. Rather, Soon-ja prefers to watch wrestling matches on television, swear like a sailor, and drink Mountain Dew. And she’s also not above teasing David about his tendency to wet the bed. What seems harsh at first gives way to a harmony between the two, captured in gentle scenes of them walking down to a nearby stream to plant the titular herb, a hardy and versatile Korean plant. These scenes reminded me of my own grandmother, a woman who taught me Polish swear words as a boy and wasn’t opposed to sticking her fingers up her nose to make me laugh. Soon-ja’s humor teaches David not to think of his condition as a crutch, leading to a grandiose, somewhat manufactured moment when the little boy with a bad heart runs to save his grandmother in a fiery climactic sequence.

The film’s perspective regularly shifts between David and his father. The most touching and immersive scenes focus on David and his grandmother, Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung), forming a bond that proves uneasy at first. He complains that she “smells like Korea” and doesn’t do what grandmothers should, like bake cookies. Rather, Soon-ja prefers to watch wrestling matches on television, swear like a sailor, and drink Mountain Dew. And she’s also not above teasing David about his tendency to wet the bed. What seems harsh at first gives way to a harmony between the two, captured in gentle scenes of them walking down to a nearby stream to plant the titular herb, a hardy and versatile Korean plant. These scenes reminded me of my own grandmother, a woman who taught me Polish swear words as a boy and wasn’t opposed to sticking her fingers up her nose to make me laugh. Soon-ja’s humor teaches David not to think of his condition as a crutch, leading to a grandiose, somewhat manufactured moment when the little boy with a bad heart runs to save his grandmother in a fiery climactic sequence.

Chung’s sentimental touch occasionally brings Minari to manipulative emotional heights, and the score by Emile Mosseri often puts too fine a point on things. You can feel Chung reaching for a Terrence Malick brand of ponderousness, but you can also feel him wanting to make the material accessible. Editor Harry Yoon often inserts cinematographer Lachlan Milne’s low-angled shots in the farm fields, capturing the grasses and windblown spider-webs in luminous imagery. Malick’s Days of Heaven (1980), which also culminates in a fire, came to mind more than once—a comparison that’s meant as a compliment and not necessarily as an indictment of Minari’s derivative quality. The film is unquestionably beautiful, unique, and familiar, and it’s no wonder it earned the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. But in the same manner that 2019’s The Farewell—another title distributed by A24—felt like a film engineered for Sundance success, this one does too.

What’s most striking about Minari are the moments when Chung seems to have captured his memories on film: dreamy shots of the family walking behind Jacob on the tractor; the scene when David is ordered to find a new punishment stick, but he returns with a blade of tall grass; the lessons imparted to David by Soon-ja, who reassures him that he’s stronger than his mother thinks. These scenes, culled from Chung’s autobiographical story, feel blissfully truthful. Minari is the kind of film that sends the viewer into their own childhood memories. How odd that I found myself searching my own experiences as a child rather than dwelling on the ones shown in the film. The film’s ability to evoke such a reaction underscores the basic humanity driving this story, regardless of culture or background. Although it’s both a Korean tale and an American one, its sweeping universality has a broad reach that finds common ground between Far East and Western cultures—just as indies by Ang Lee or Lulu Wang have before with their sincerity and tenderness.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review