Milk

By Brian Eggert |

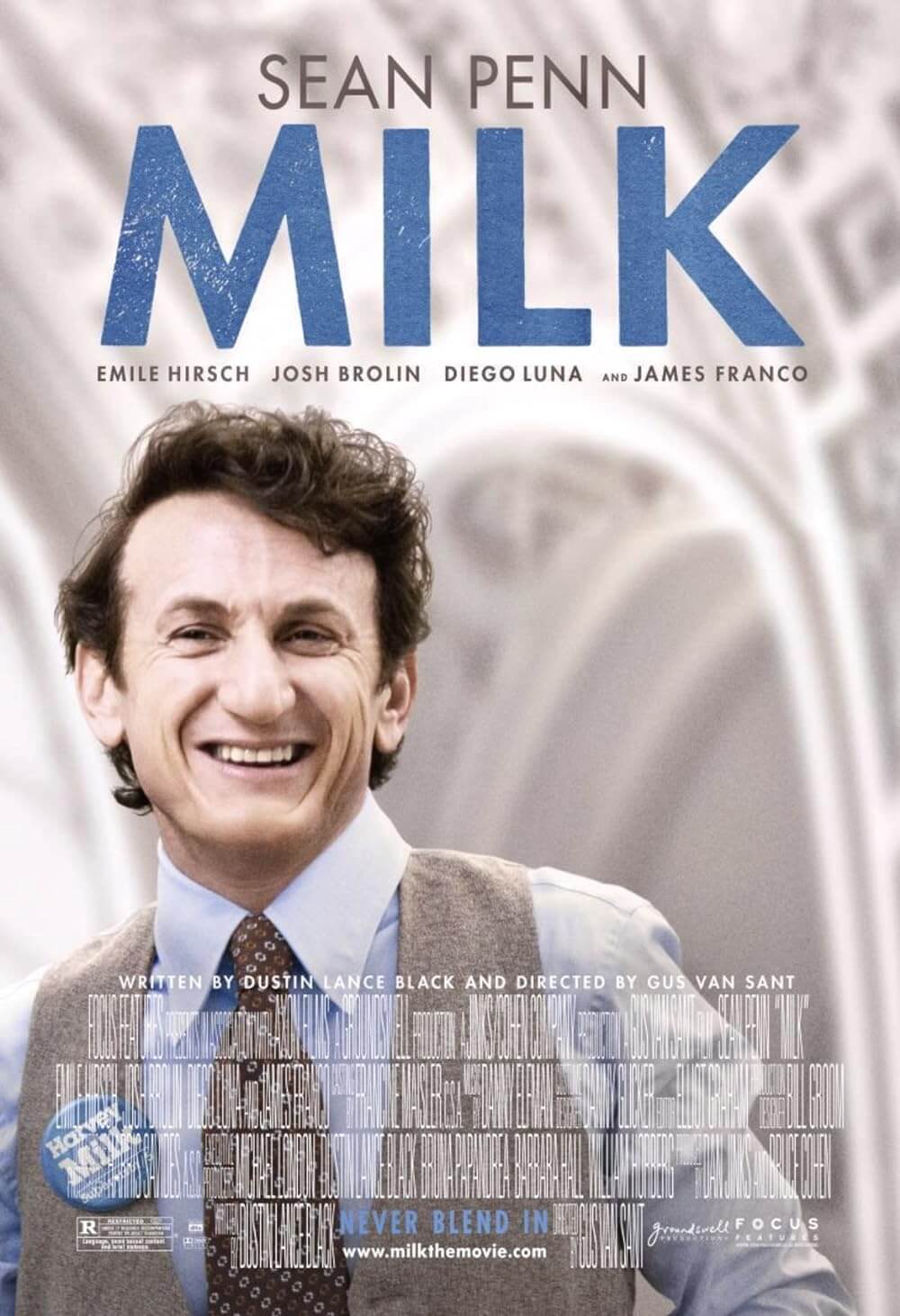

Harvey Milk was in his forties when he moved to San Francisco in 1972, as many gays did in that era, leaving his former life on the East Coast to open a camera shop on Castro Street. He watched the gay community around him take abuse from local police and unfriendly businesses, and then decided to change things. Promoting a movement to unite the neighborhood around him into a thriving one, he ran for office and eventually became City Supervisor, lobbying for gay rights, but more than that, for the hope that the American Dream still exists. Director Gus Van Sant opens Milk with a montage of anti-gay arrests, inspired by prejudicial persecution in the name of religious conviction. In standard biopic form, Van Sant then structures the film around the recording of Milk’s prognostic “in the event of my assassination” audio tape, which depicts Harvey (Sean Penn), seated at his kitchen table recounting his life—that is, his eight years truly lived in San Francisco.

Having found a lasting love in Scott Smith (James Franco), Harvey’s drive for office wears upon his personal life through several failed campaigns. Hate mail and widespread publicity are bound to add friction to a relationship, and though Harvey is a loving man, his relationship with Scott slowly spreads thin with each new step achieved in another unsuccessful run for office. As pressures increase, Scott leaves, later replaced by the pouting and suicidal Jack Lira (Diego Luna). Van Sant spends as much time in Harvey’s private life as he does his subject’s public one, reaching an intimacy not matched since his 1991 effort, My Own Private Idaho.

Harvey’s chief political conflict arises in the form of Southern Baptist Anita Bryant, the commercial actress and singer. Bryant appears only in vintage footage. Van Sant refuses to cast an actress to portray her, I believe, because her outrageous claims might be misconstrued as dramatization. Video from her campaigns against the “homosexual agenda” contains a very real, very terrifying level of intolerance and an even more shocking degree of support. Along with her bigoted cohort Senator John Briggs (Denis O’Hare), her crusade to allow employers to terminate people based on their sexual preference labeled gays pedophiles and worse. How do you fight such ignorance? One of the best ways we determine Harvey’s greatness is by examining those he fought; in this case, they don’t get much worse. Each time Harvey addresses an audience, he announces, “My name is Harvey Milk, and I want to recruit you,” mocking Bryant’s theory that gays set out to convert and recruit (as if Christians never tried to covert and recruit).

Sean Penn plays Harvey Milk as if overcome by another personality, allowing us to forget there’s an amazing actor at work and simply accept the person as presented. Penn’s costar Josh Brolin did something similar this year in Oliver Stone’s W., playing our current president. Brolin too embodies his role as Harvey’s coworker, former Supervisor Dan White, the man that would shoot and kill both Harvey and Mayor George Moscone (Victor Garber). Becoming a martyr for his cause, Harvey’s death spawned riotous retaliations over the leniency of White’s subsequent sentencing.

Watching Milk felt like taking a time machine hundreds of years into the past. And then the sad realization comes that the events depicted occurred only thirty years ago. If we’ve grown since then—which is another, debatable issue altogether—then it’s because of Harvey Milk. Van Sant broadens the eight years of the film, a short period considering the extensive coverage of some Hollywood biopics. But more than a historical account, Van Sant’s film becomes a personal drama about an individual, versus merely his grand accomplishments. Humanizing the martyr doesn’t deter from his importance, however, as Harvey’s trailblazing was more than a political “issue” to be shaped in support of a career. It was precisely the opposite, that Harvey’s momentous benchmark contributions to American culture were based on his passionate belief that the disenfranchised need to take a stand.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review