Reader's Choice

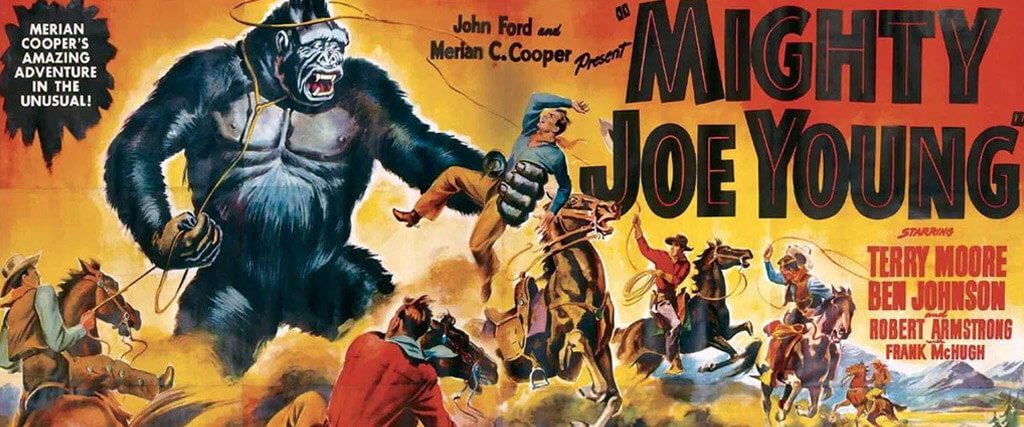

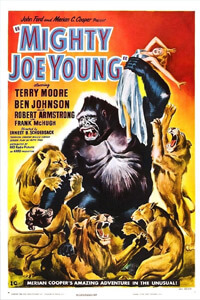

Mighty Joe Young

By Brian Eggert |

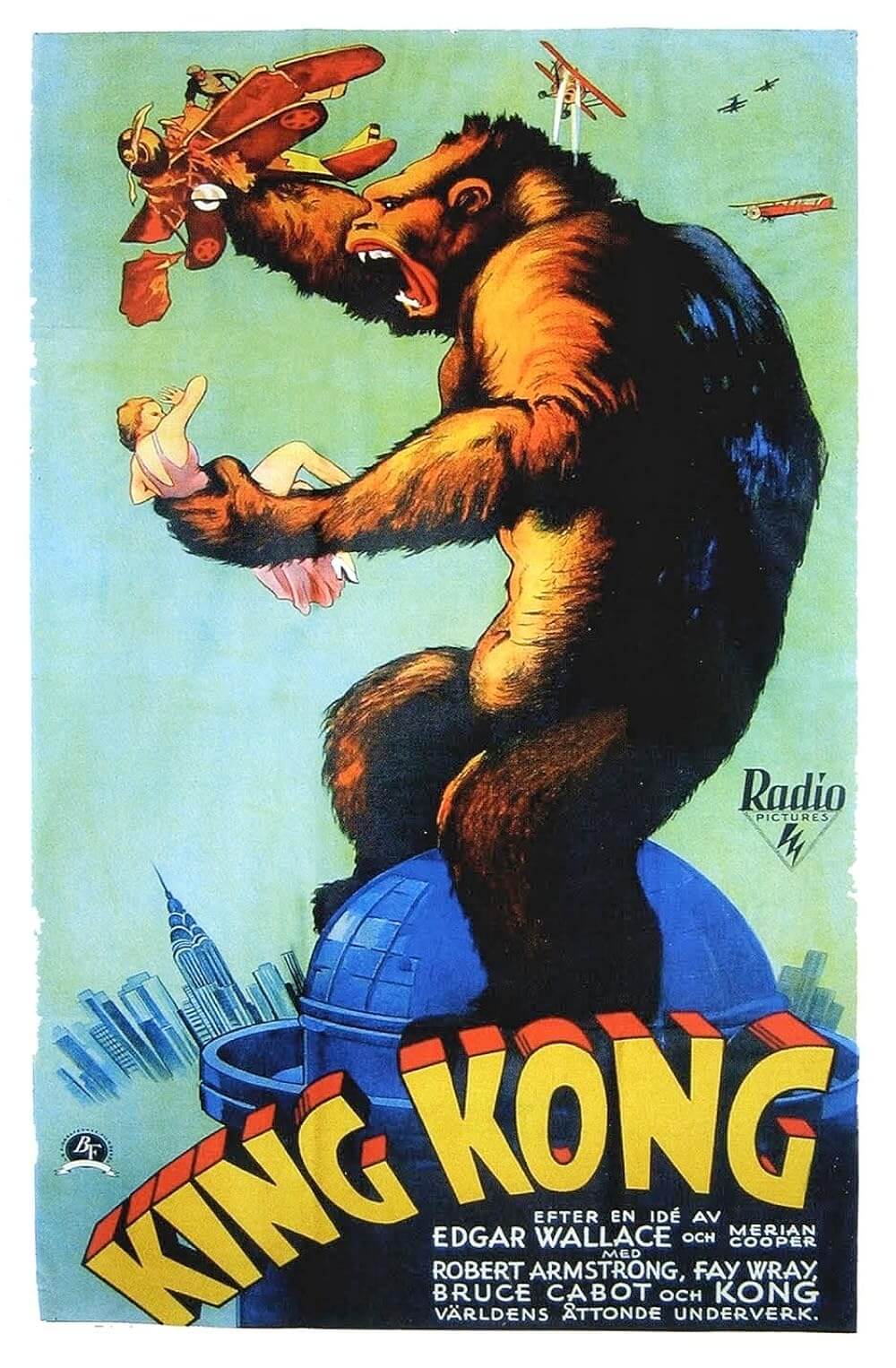

More than a decade passed between 1933, the release year of both King Kong and its rushed-to-production sequel Son of Kong, and the 1949 arrival of their distant cousin, Mighty Joe Young. The Second World War had come and gone in the interim, leaving many Hollywood filmmakers to explore darker themes, offbeat heroes, and cynical worldviews. But not Merian C. Cooper, whose RKO adventure swiped its imagery and story structure from his original Kong concept and applied a family-friendly skin. Rather than confront the world’s grim reality with an influx of posthumous narrators and Freudian dream sequences that emerged after the war in studio cinema, the Kong parentage (producer Cooper, director Ernest B. Schoedsack, and screenwriter Ruth Rose) supplied their audience with a throwback of sorts. Not only did Mighty Joe Young tap into fond pre-war memories of escapist adventures like King Kong, but it also presented an earnest and downright corny good time. It remains a landmark of stop-motion animation thanks to Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen’s Oscar-winning efforts, but its plotting and treatment of animals throughout may cause modern viewers to cringe.

A curious, unintended outcome of King Kong led to the creation of Mighty Joe Young. Although Cooper and company sought to frighten and thrill moviegoers with their original great ape, many viewers, especially children, viewed Kong with empathy and fascination. Cooper, who headed a production unit at RKO, decided to capitalize on that trend and produce a rehash of his original concept; however, this time, the ape would be the hero of a humor-laden story with plenty of kid appeal. The war meant production on the concept would have to wait until the late 1940s, but the story was already clear in Cooper’s mind. Rose, who contributed to the original King Kong screenplay, receives full credit for the script—an unmistakable copy of the original. Once again, Robert Armstrong plays a blowhard and showman, here named Max O’Hara, who plans an expedition to “darkest Africa” to find material for his Hollywood nightclub, called the Golden Safari. He finds a massive gorilla, cons its naive owner Jill Young (Terry Moore, who married Howard Hughes before the film’s release) into signing it over, and returns home for a showy stage performance. Before long, the animal causes a ruckus, but this time around, the audience is rooting for the gorilla.

Among the many children inspired by King Kong was Harryhausen, who saw the original film at the age of 13 at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and thereafter remained obsessed with learning how O’Brien and his crew completed the special FX. With film books all but nonexistent at the time, Harryhausen experimented with stop-motion and sculpting on his own personal projects, learning from trial and error. He wrote fan letters to O’Brien and even had his work critiqued by the legendary model-maker. It took years of Harryhausen studying musculature and experimenting on other projects, including the Puppetoon shorts for George Pal, before he was ready. His work on a passion project called Evolution, which he completed between 1939 and 1940, finally earned O’Brien’s attention. After the war, O’Brien hired Harryhausen to assist with work on Mighty Joe Young, which began special FX preparations in 1947. Using four models designed by Marcel Delgado, who also sculpted the original Kong models, O’Brien and Harryhausen operated a Joe Young armature of more than 150 parts. This time, the design was based on actual gorillas—one gorilla, actually, named Bushman, whose home was the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. It would be Harryhausen’s breakthrough, as he completed over eighty percent of the stop-motion work required on the gorilla models and various human sculptures used in the film.

Among the many children inspired by King Kong was Harryhausen, who saw the original film at the age of 13 at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and thereafter remained obsessed with learning how O’Brien and his crew completed the special FX. With film books all but nonexistent at the time, Harryhausen experimented with stop-motion and sculpting on his own personal projects, learning from trial and error. He wrote fan letters to O’Brien and even had his work critiqued by the legendary model-maker. It took years of Harryhausen studying musculature and experimenting on other projects, including the Puppetoon shorts for George Pal, before he was ready. His work on a passion project called Evolution, which he completed between 1939 and 1940, finally earned O’Brien’s attention. After the war, O’Brien hired Harryhausen to assist with work on Mighty Joe Young, which began special FX preparations in 1947. Using four models designed by Marcel Delgado, who also sculpted the original Kong models, O’Brien and Harryhausen operated a Joe Young armature of more than 150 parts. This time, the design was based on actual gorillas—one gorilla, actually, named Bushman, whose home was the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. It would be Harryhausen’s breakthrough, as he completed over eighty percent of the stop-motion work required on the gorilla models and various human sculptures used in the film.

If Mighty Joe Young has a lasting place in film history, it’s because Harryhausen’s special FX elevate it. They led to a career of iconic stop-motion extravaganzas: The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Jason and the Argonauts (1963), and others. The film’s story, however, leaves much to be desired. The original review in The New York Times put it succinctly: “The wonder of ‘Mighty Joe Young’ is the mobility of the mechanical star, but even that novelty wears thin after a while.” It’s a humdrum tale with a trite and jokey quality, which the staff critic at Variety observed as “fun to laugh at and with, loaded with incredible corn, plenty of humor, and a robot gorilla who becomes a genuine hero.” The first scenes take us to Africa (no country or region specified, just “Africa”), where the young Jill bargains with two locals, trading a flashlight and other nicknacks for a baby ape. She names the cute little guy “Joe,” and 12 years later, he’s an oversized gorilla, living with the teenaged Jill on an isolated plantation of sorts.

Perhaps now is a good time to mention the film’s other producer, John Ford, whose name was already synonymous with the Western genre. Under their production company Argosy, Ford had teamed with Cooper to make his cavalry trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande), as well as Mighty Joe Young. As a result, the film feels like a combination of Cooper’s ape films and Ford’s Westerns—albeit directed by Schoedsack, who was legally blind at the time (not that it mattered; most of the story takes place in the special FX department). Enter Gregg, played by Ford regular Ben Johnson, a tall cowpoke with a talent for lassos. O’Hara hires Gregg for an expedition to capture lions in Africa, lending the picture a marketable “jungle cowboys” vibe. Once there, they meet Joe and Jill, and O’Hara convinces them to headline his Africa-themed nightclub, complete with lions in a glass habitat behind the bar. In Hollywood, O’Hara arranges a series of (humiliating) performances: Joe holds a piano on a platform as Jill plays his favorite song, “Beautiful Dreamer;” he plays tug-o-war against ten strongmen in leopard-print getups; he endures the crowd tossing oversized coins at him. In each performance, the crowd is a nightmare, laughing and pointing like drunkards from a Pieter Bruegel painting.

Three such drunks set the conflict into motion. For a lark, they give Joe whiskey and burn him with a lighter, sending Joe into a frenzy that leaves the nightclub in ruins. Then, a judge orders Joe to be put down, prompting a daring escape planned by O’Hara, Gregg, and Jill. There’s a chase, with police not far behind, and just before Gregg and Jill make it to the docks for a ship to Africa, there’s a brief and random detour at a burning school for children. How the school started on fire or why our heroes decided to stop in the middle of a thrilling chase are matters of bad screenwriting, arranged to endear the audience to Joe. In any case, Gregg, using his knack for lassos, and Joe, using his climbing abilities, save several children from the fire. The sequence was originally exhibited using red-tinted frames and makes little sense within the greater (black-and-white) story. Endear it does, though, as Jill and Gregg—now a couple in an underdeveloped romance, even though it has been established that Jill is “underage”—return with Joe to Africa. They send a filmed message back to O’Hara, thus the audience: “Goodbye from Joe Young.”

Three such drunks set the conflict into motion. For a lark, they give Joe whiskey and burn him with a lighter, sending Joe into a frenzy that leaves the nightclub in ruins. Then, a judge orders Joe to be put down, prompting a daring escape planned by O’Hara, Gregg, and Jill. There’s a chase, with police not far behind, and just before Gregg and Jill make it to the docks for a ship to Africa, there’s a brief and random detour at a burning school for children. How the school started on fire or why our heroes decided to stop in the middle of a thrilling chase are matters of bad screenwriting, arranged to endear the audience to Joe. In any case, Gregg, using his knack for lassos, and Joe, using his climbing abilities, save several children from the fire. The sequence was originally exhibited using red-tinted frames and makes little sense within the greater (black-and-white) story. Endear it does, though, as Jill and Gregg—now a couple in an underdeveloped romance, even though it has been established that Jill is “underage”—return with Joe to Africa. They send a filmed message back to O’Hara, thus the audience: “Goodbye from Joe Young.”

Mighty Joe Young may have been a hunk of cute escapism for late-1940s audiences, but today there’s some disturbing animal peril that may trigger the animal-sensitive viewer (myself included). Most of these scenes involve actual lions. When we first meet Joe in Africa, he attacks a caged lion, smashing the wood container. The lion inside, a real-life big cat inserted into the stop-motion shot, looks terrified and seems to be in real distress. Who knows what the animal handlers did to achieve this reaction. The lions at O’Hara’s nightclub also look terrified when Joe rampages, smashing the glass of their container. As Joe goes berserk, the filmmakers drop actual lions on dinner tables, send them slipping across the slick club floor, and slam doors on their faces when they try to escape. Frankly, it’s disturbing and difficult to watch. Elsewhere, even the scenes with Joe—who looks more zoologically correct than Kong, more like an actual gorilla than the impossible amalgam of ape and monkey characteristics seen in the 1933 film—prove a challenge to endure when he’s put in harm’s way. But maybe that’s a testament to Harryhausen’s talent at creating a believable character out of a metal frame, fur, and putty.

Though the rest of the world changed and evolved after the Second World War, Cooper’s approach to Mighty Joe Young still holds a troublesome worldview. James Snead argues that Joe’s return to Africa “actualizes an implicit, but failed, inclination of King Kong—to humanize, assimilate, and domesticate black ‘otherness’” through colonialism. To be sure, Jill and Gregg make Africa their home, complete with “servants and field hands” tending to them. Even so, many of the racist overtones of King Kong remain less integral here, leaving viewers with a fully realized ape character at the center of a pleasant enough yarn. Joe is curious, playful, and heartwarming in his defense of Jill. If only the filmmakers showed equal sympathy for the real-life animals on display, Mighty Joe Young might be easier to enjoy. Instead, we’re left with poorly developed human characters in sometimes laughable, often unmotivated situations, making the film essential for stop-motion enthusiasts but difficult to recommend otherwise.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Frazier, Valerie. “King Kong’s Reign Continues: King Kong as a Sign of Shifting Racial Politics.” CLA Journal, vol. 51, no. 2, 2007, pp. 186–205. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/44325418. Accessed 21 Apr. 2020.

Morton, Ray. King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2005.

Snead, James A. White Screens/Black Images: Hollywood From the Dark Side. Routledge, 1994.

Vaz, Mark Cotta. Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villard, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review