Mifune: The Last Samurai

By Brian Eggert |

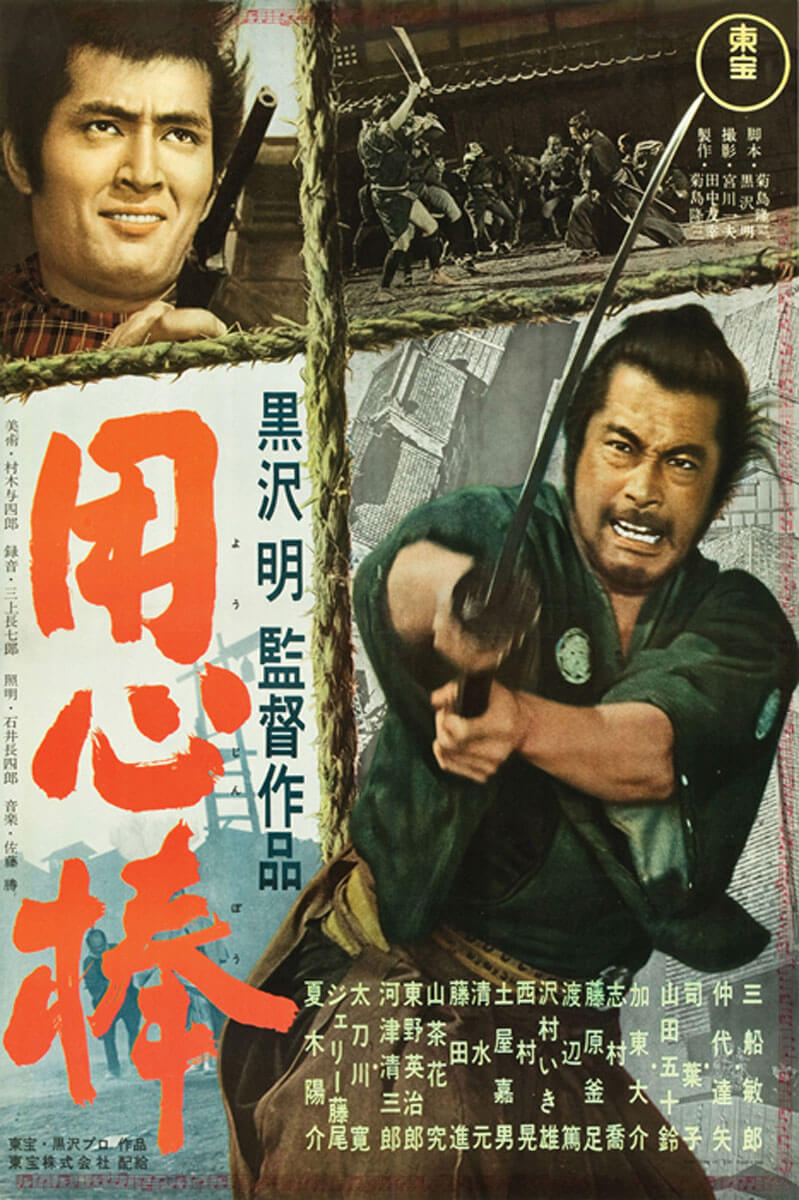

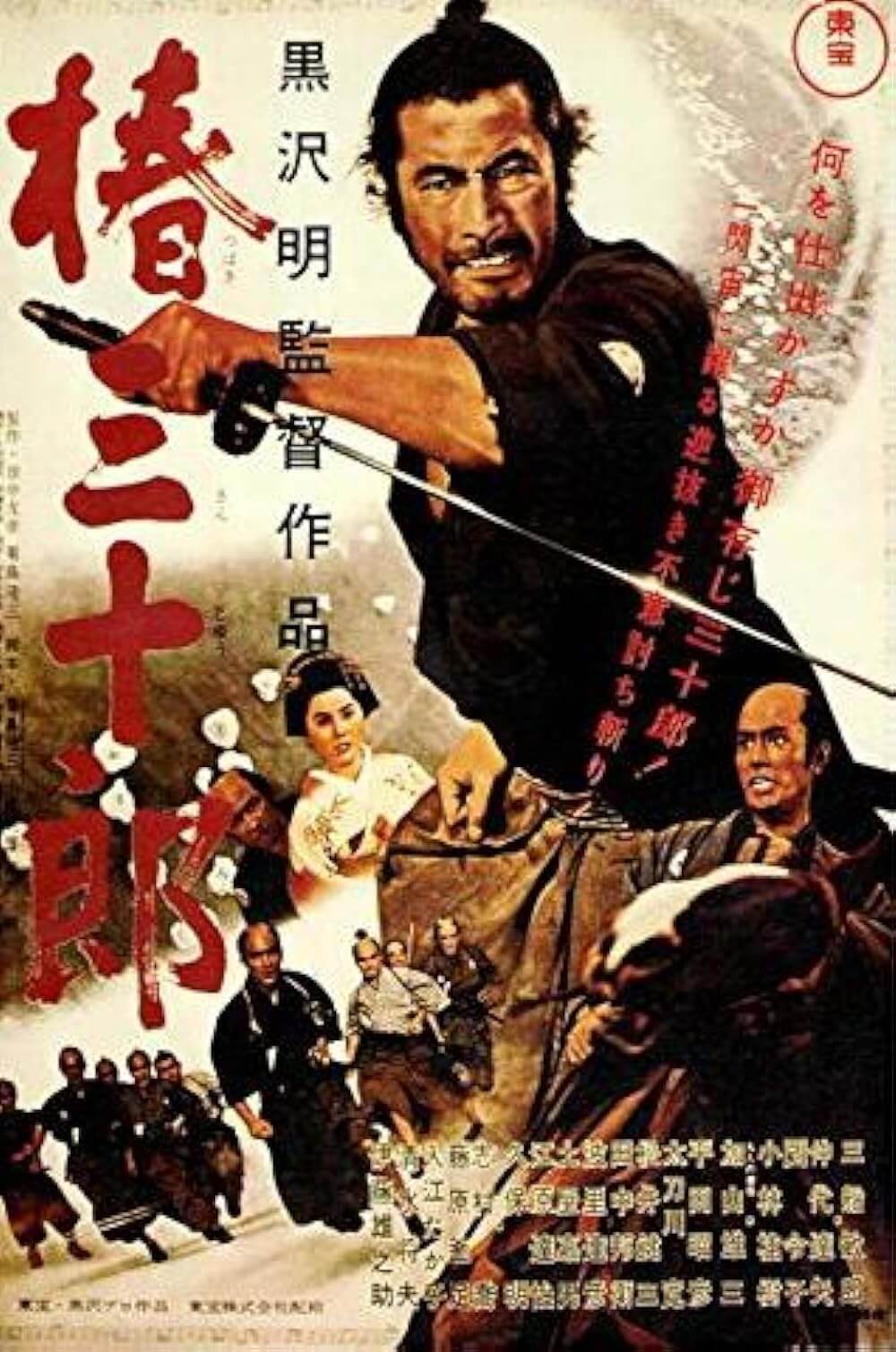

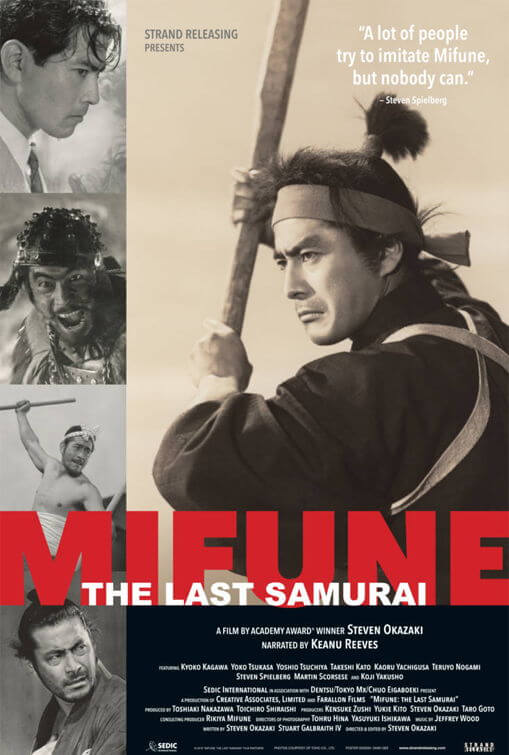

Toshiro Mifune appeared in 126 films and, from 1946 to his death in 1997, was Japan’s most famous actor. Sixteen of those films were directed by Japanese master Akira Kurosawa, including some of the most important and internationally renowned pictures of the last century: Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954), Yojimbo (1961), and Red Beard (1965), among others. In his Kurosawa works, Mifune embodied a quality Steven Spielberg has described as “from the Earth,” meaning the actor’s style was primal, as though something had been unleashed. Mifune had piercing eyes and a vitality onscreen that many actors have tried to imitate, but none have mastered. No wonder he became an instant cultural icon in Japan and beyond. Although many of his films outside of his Kurosawa collaborations are often overlooked, Mifune demonstrated his array of talent with other directors such as Kenji Mizoguchi, Masaki Kobayashi, and even Spielberg himself.

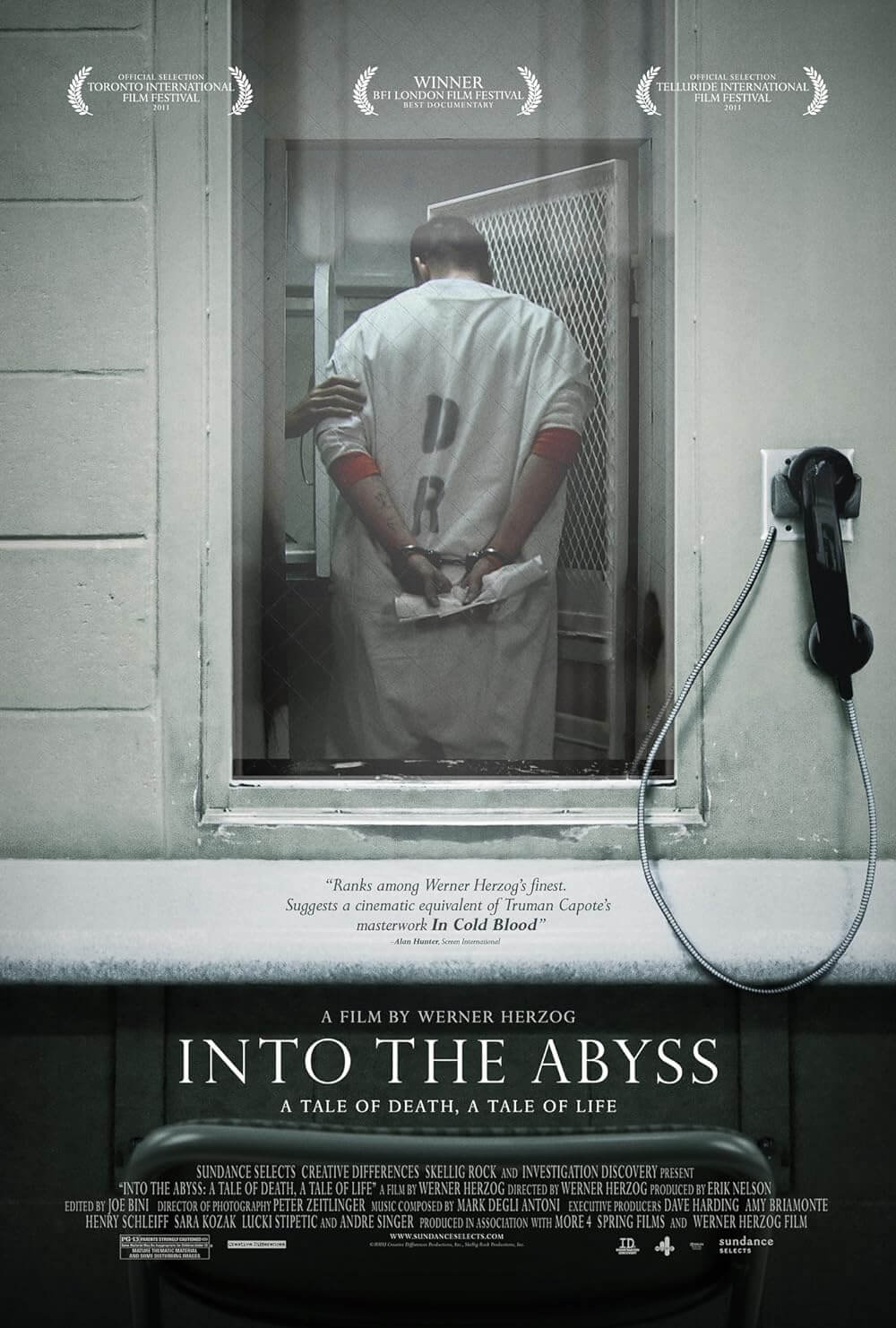

Steven Okazaki offers an elementary look at Mifune’s life, screen presence, and influence in his documentary, Mifune: The Last Samurai. Narrated by Keanu Reeves, Okazaki’s doc considers his frequent theme of Eastern influence on Western culture and vice versa. Okazaki earned an Oscar nomination for his 1986 doc Unfinished Business, about the detainment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans in camps after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He also explored the horrific aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in White Light/Black Rain: The Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from 2007. Fortunately, with Mifune: The Last Samurai, Okazaki considers a topic that has brought together Eastern and Western cultures in a way that is important and lasting, but also positive.

The 80-minute doc begins with a brief history of the samurai and its presence in the earliest Japanese cinema. Although samurai ideologies are meant to serve as connective tissue in the doc’s remaining runtime, Okazaki never quite ties together samurai beliefs with Mifune, aside from the actor’s frequent roles as a samurai warrior. Samurai warriors followed the bushido code, a doctrine that emphasized prudent and honorable lifestyle, along with jealous devotion to a single master-employer. As Okazaki’s documentary shows, Mifune was an inward man defined by his intense performances that were unique in Japanese cinema for their expressiveness. For Japanese audiences, he became the quintessential samurai actor. But in his personal life, Okazaki defines Mifune as a quiet individual with an affinity for fast cars and hard-drinking, sometimes at the same time.

Born in 1920 of Japanese parents, Mifune grew up in Manchuria, China, and only arrived in Japan when he was twenty. By that time, World War II was raging, and he served by training young pilots; though, instead of telling kamikazes to say their final prayers to the emperor, he told them to think of their mothers. A sensitive and introspective man, after the war Mifune wanted to become a photographer at Tokyo’s Toho studios, but he was quickly discovered by Kurosawa and hired as a performer. Their first collaboration as actor-director, Drunken Angel from 1948, was also Kurosawa’s first major effort as an auteur. The sometimes tumultuous relationship between Mifune and Kurosawa, as well as the influence of their films together, remain the central focus of Okazaki’s doc.

Mifune: The Last Samurai proceeds in a linear fashion, complete with archival footage, stills, and testimonials from a variety of Mifune’s fellow actors. Among them is Kanzo Uni, a stunt choreographer who tells lively anecdotes with his own verbal sound FX and animated gestures. Uni proudly proclaims he was killed by Mifune more than 100 times onscreen. Other contributors include Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader, and Spielberg, but it’s rather surprising that filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas do not appear, given their outspoken fondness for the Mifune-Kurosawa films. (After all, The Hidden Fortress from 1958 inspired Lucas to create Star Wars; he even offered Mifune the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi, which the actor’s American agent advised him to turn down.) Throughout the doc, Mifune’s family takes a smaller role; his son, Shiro, provides mere glimpses into the figure’s personal life.

In a 1998 article featured in The Village Voice, coincidentally titled “The Last Samurai,” Michael Atkinson wrote that Mifune embodied archetypal postwar Japanese sensibilities by being “inscrutable, unscrupulous, and ready for battle.” Only in this vague way does Mifune, as a human being, resemble a samurai. It’s a superficial association that goes no deeper than asking Reeves to narrate because, presumably, he starred in the underwhelming Japanese samurai-fantasy 47 Ronin. Nevertheless, Okazaki provides a solid, at-a-glance introduction to Toshiro Mifune. Okazaki’s work may lack an in-depth quality that would have made the doc more probing and vital, but cinéastes just discovering the Mifune-Kurosawa collaborations are encouraged to seek out Mifune: The Last Samurai to better understand the actor’s immeasurable impact on both Japanese and American cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review