Midsommar

By Brian Eggert |

When Midsommar’s group of American college students journeys into the isolated farming commune of Hårga, Sweden, led by their classmate who grew up there, director Ari Aster’s camera turns over to an inverted angle, entering us into a world upside down. The quiet, idyllic village in the middle of the forest may not seem out of the ordinary, but its closeness to Nature and the uncommon life cycle embraced by its inhabitants reveal a rejection of traditional western beliefs. What begins as a compelling anthropological investigation unravels into a pagan nightmare of folk horror, where the midnight sun, psychedelia, sexual enchantments, sacrifice, and worship of the natural world each have a vital role in the ensuing nine-day festival. A haunting and uncanny experience, Midsommar is Aster’s assured second film that, similarly to his debut with last year’s Hereditary, draws from dozens of ingrained horror sources and motifs to instill something altogether inspired. Aster wields a two-pronged setup that pokes at feelings of anxiety about remote communities and their link to an untamed wilderness, while also presenting characters whose interpersonal drama underscores every potently disturbing situation in the film.

Once again, Aster scars his characters with a horrific trauma that reverberates through the remainder of the film. Dani (Florence Pugh) and her boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor) are on the verge of a breakup after four years together. But she has issues with a disturbed sibling that leads to a tragic death in the family, thereby locking Christian into a relationship that his friends compel him to leave. When Christian and his friends—post-grad student Josh (William Jackson Harper) and toolbox Mark (Will Poulter)—arrange to visit Sweden for a rare festival held at the home of their friend, Pelle (Vilhelm Blomgren), it’s out of obligation that he invites Dani. Disrupting the intended boys’ trip vibe, Dani’s psychological state leaves her suspended, ever on the verge of a breakdown. She makes every human interaction a layered one, while Christian tries, badly, to be accommodating and supportive, but he’s so disingenuous and selfish that even the smallest encounters make us squirm with social discomfort. Adding to Dani’s persistent feelings of solitude and disassociation is the physically isolating effect of Hårga, the location of a summer solstice ceremony that occurs only every 90 years and proves more ritualistic than carnivalesque.

Aster brings to life an intricately detailed community, where the fair-haired men and women drape themselves in dress-like whites to symbolize “Nature’s hermaphroditic qualities,” and the diegetic score originates from chantlike singing accompanied by violins and animal-skin drums. The Hårga people welcome the outsiders with suspicious cheerfulness, while the fledgling scholars in the group observe the bustling, floral activity with an academic distance. Josh and Christian both want to write about the commune for their theses, and so they regard the increasingly unsettling peculiarities with objective curiosity. The community has an off-limits temple at the edge of the village; teaches their children to carve rune stones; and sleeps in a shared space with murals of seduction, intercourse, and sacrifice on the walls. Seemingly harmless cultural curiosities aside, at first glance it’s the wild party some of the boys were hoping for, complete with mind-expanding drugs and come hither glances from a few of the village women. But it doesn’t take long for the goodwill to be upset by a shocking ättestupa suicide ritual, questions of inbreeding, and the distressing contents of meat pies.

Using a clever blend of actual ancient practices and the cinematic tradition of folklore as a source of horror, Aster confines his audience in a place we do not understand, terrifying us with the uncertainty of what comes next. Moreover, Midsommar’s theme of academic observation, combined with its conceit as a horror film set in perpetual daylight, allows the viewer to watch with piqued inquisitiveness and foreboding, as there’s a mystery, but shadows hide nothing. It’s the kind of experience that makes you sit up in your seat, equally fascinated and troubled by what you’re seeing. What’s best about the film are small and creepy details that implant the film’s sense of dread, such as a moment when a woman’s scream is heard in the distance. The Americans react, startled, searching for the sound, while the villagers seem unconcerned if not accustomed to the occasional shriek. If the villagers had reacted too, the Americans might have panicked. But no one seems concerned, so why worry? The persistent sense of not knowing what’s going on or what will happen next proves deeply effective in creating an ominous mood and then accenting that mood with scenes of sheer horror and violence.

Using a clever blend of actual ancient practices and the cinematic tradition of folklore as a source of horror, Aster confines his audience in a place we do not understand, terrifying us with the uncertainty of what comes next. Moreover, Midsommar’s theme of academic observation, combined with its conceit as a horror film set in perpetual daylight, allows the viewer to watch with piqued inquisitiveness and foreboding, as there’s a mystery, but shadows hide nothing. It’s the kind of experience that makes you sit up in your seat, equally fascinated and troubled by what you’re seeing. What’s best about the film are small and creepy details that implant the film’s sense of dread, such as a moment when a woman’s scream is heard in the distance. The Americans react, startled, searching for the sound, while the villagers seem unconcerned if not accustomed to the occasional shriek. If the villagers had reacted too, the Americans might have panicked. But no one seems concerned, so why worry? The persistent sense of not knowing what’s going on or what will happen next proves deeply effective in creating an ominous mood and then accenting that mood with scenes of sheer horror and violence.

Working alongside cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski, Aster’s visuals looks clean, brightly colored, and at times hallucinatory with a touch of world-bending CGI. But within Aster’s mannered yet austere aesthetic presentation is an inclination toward qualities of so-called elevated horror, a label designed by some promotional wizard to distinguish degrees of horror for separate demographics. Whereas something considered to be an example of lowbrow horror may not appeal to sophisticates who view horror as beneath them, the label of “elevated horror” suggests a higher social or intellectual significance in the films of, say, Jordan Peele next to the latest supernatural offering in the “Conjuring Universe.” It’s ultimately a bogus way to color horror as something other than horror, so audiences who wouldn’t normally associate with genre films have a reason to venture into dark territory. In any case, Aster’s approach to horror contains deliberate pacing and elaborately constructed visuals to luxuriate in long takes of the beautifully conceived village, with locations in Budapest standing in for Sweden, and their unseemly cultural flourishes.

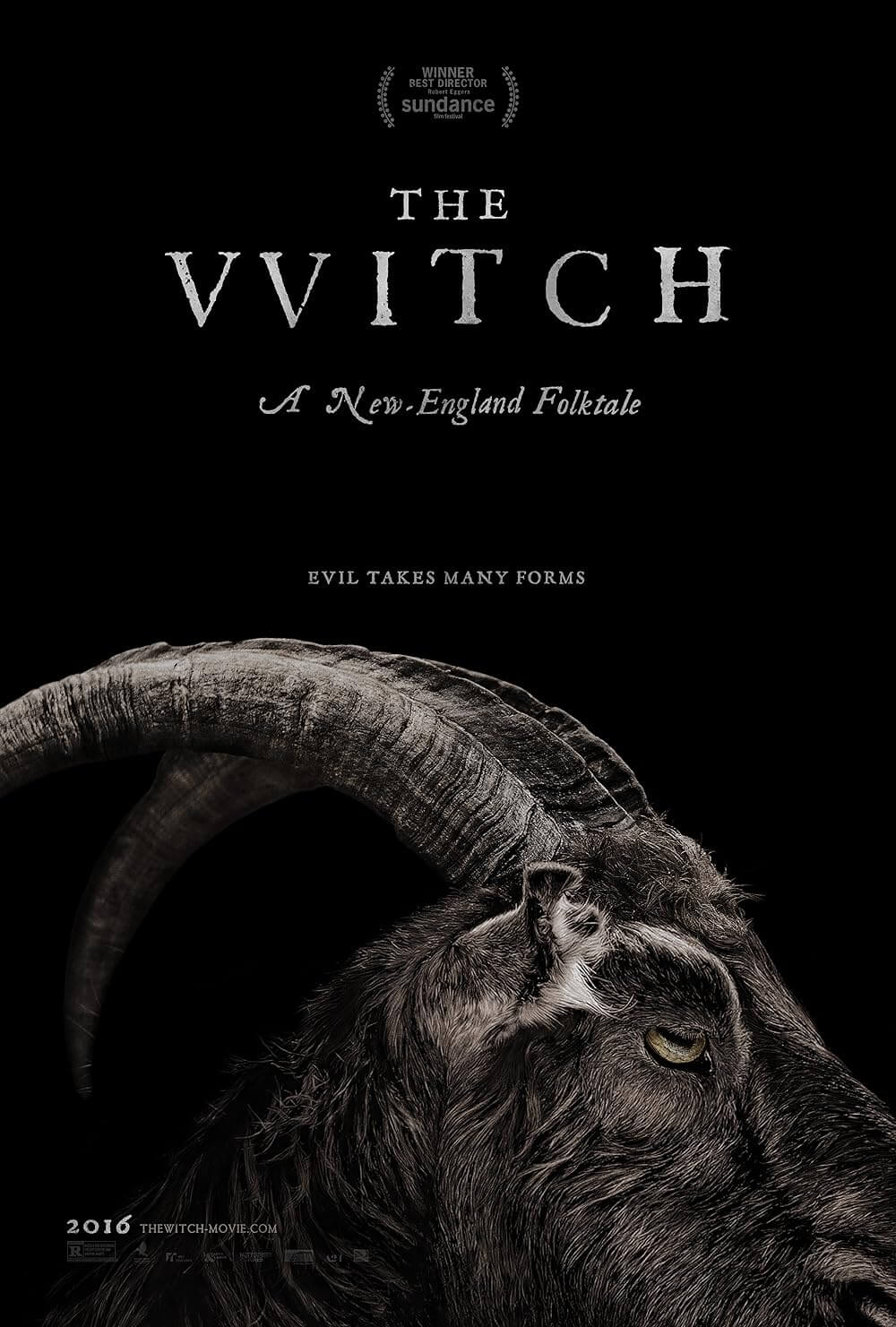

Made in the tradition of films like The Wicker Man (1973) or more recently The Witch (2015)—films that exploit the fear of pre-Christian practices used in neopaganism—Aster does more than immerse the viewer in a setting of strange customs. Midsommar might be the ultimate bad breakup movie, as the whole thing seems to hinge less on the festival of horrors than the crumbling relationship between Dani and Christian, which receives closure with the chilling last shot. Aster treats his characters with emotional complexity and gets inside Dani’s head, allowing for excellent performances by Pugh and Reynor (whose character might experience the ultimate moment of male vulnerability). Similar to Toni Collette’s tour-de-force performance in Hereditary, Pugh is acting on a level that creates a realistic psychological portrait, making every scene another facet into her character’s frame of mind. It’s the quality of the acting over the subject matter that makes Midsommar a singular piece of filmmaking, whereas the sharp lensing and gorgeous production design feel like a bonus.

Aster is clearly a talented filmmaker interested in themes of emotional distress, which are thus reflected and symbolized by an environment of horror. Both of his features have used cultism, ritualism, family, and community to create feelings of isolation and terror, leading to a natural blend of the psychological and physical. But if there’s any minor problem with Midsommar, the protracted runtime of nearly two-and-a-half-hours proceeds at a measured pace, occasionally allowing the viewer to drift off and think about what we’re watching, as opposed to complete and total immersion for the duration of the film—especially in the last act, when outside influences have subdued the characters and the audience has less to engage with. But these moments are rare, and the lasting effect of Midsommar is a feeling of awe toward the witnessed horror and the curious sense of connectivity and liberation achieved through the film. It’s a feeling wonderfully captured as Dani screams an awful, guttural wail in a moment of betrayal, and around her, the Hårga women match her cries to achieve a sublime harmony.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review