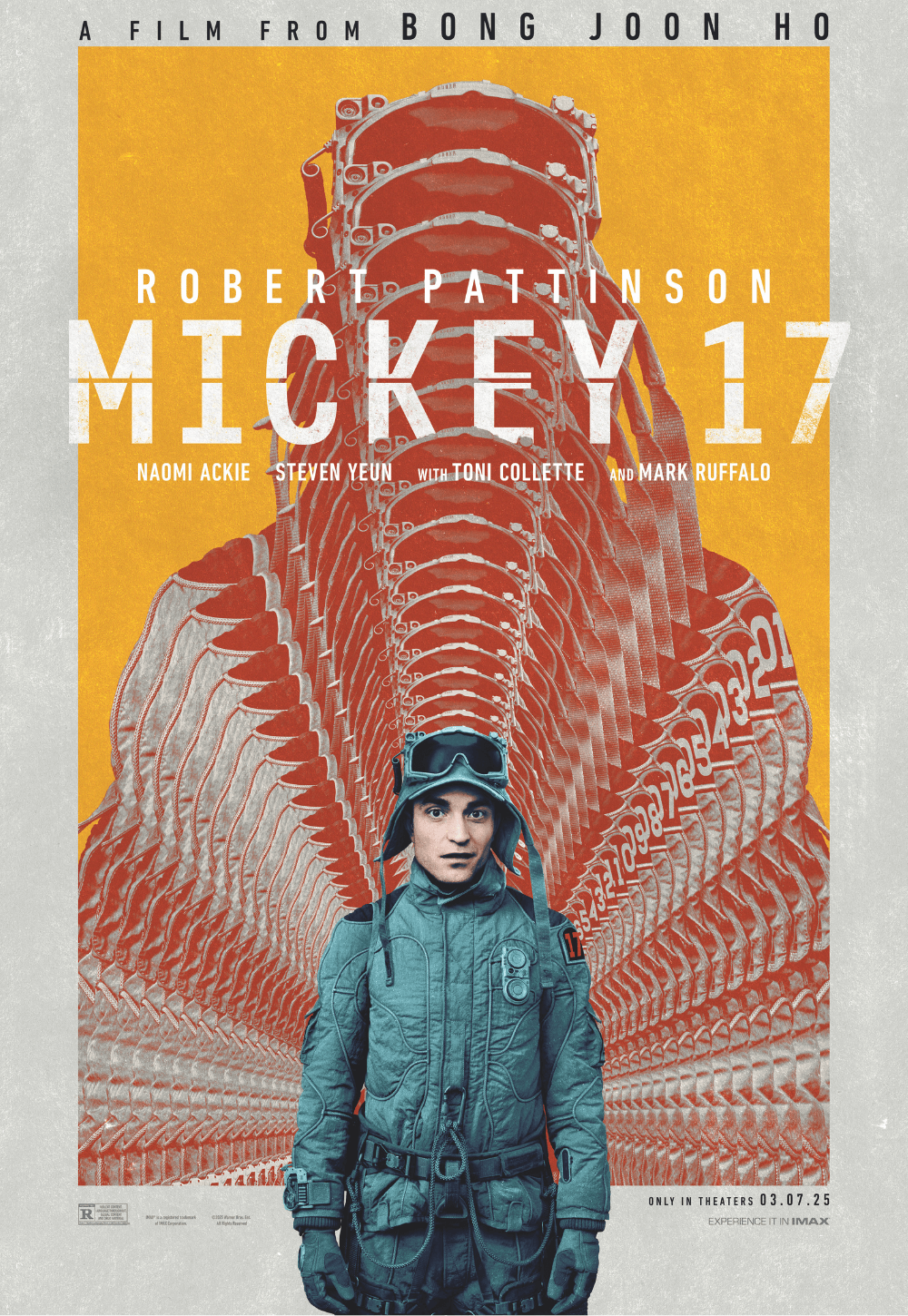

Mickey 17

By Brian Eggert |

“Nice knowin’ ‘ya. Have a nice death. See you tomorrow.”

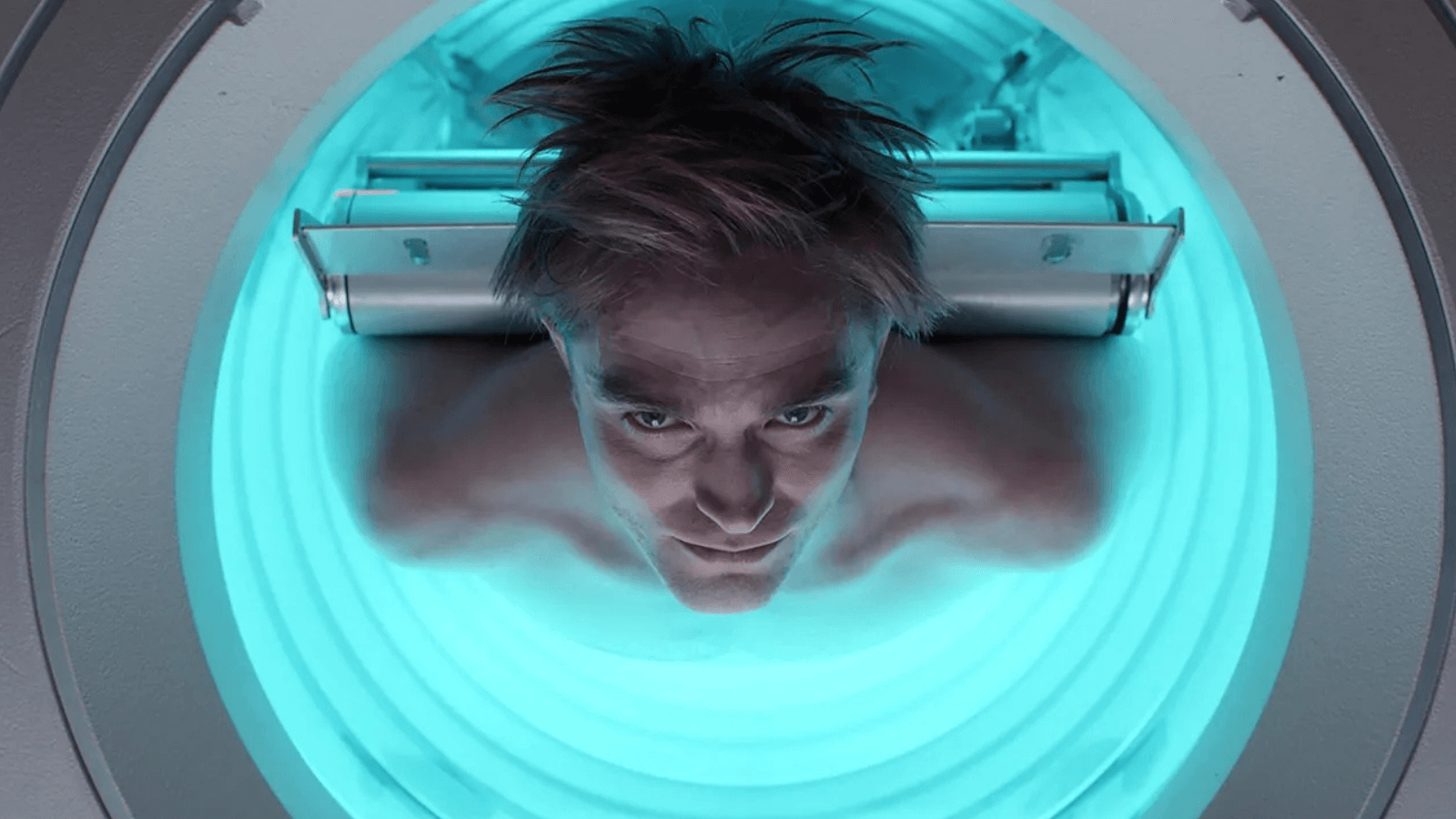

In Mickey 17, Robert Pattinson’s character dies over and over. He’s an Expendable class of worker enlisted for perilous tasks no one else could perform without mortal consequences. Part crash-test dummy, part subject for clinical trials, part replaceable human capital, Mickey Barnes often dies on the job. When he does, the scientists overseeing a planet colonizing mission squeeze out another Mickey from a human-grade Play-Doh Fun Factory. His memory and body identical to earlier iterations, Mickey survives in a series of cloned copies whose raw materials come from organic waste. His existence prompts questions about whether he’s human or something else, whether his life has the same value as other, non-cloned people. But that barely scratches the surface of the ideas loaded into Mickey 17, a visionary achievement. Here’s a film so inspired, darkly funny, harrowing, energetic, and overflowing with story and themes that it’s bound to be polarizing—alternately deemed messy and unfocused or inventive and original. In the best ways, the experience brought to mind the work of Terry Gilliam, the Wachowskis, and, of course, Bong Joon-ho.

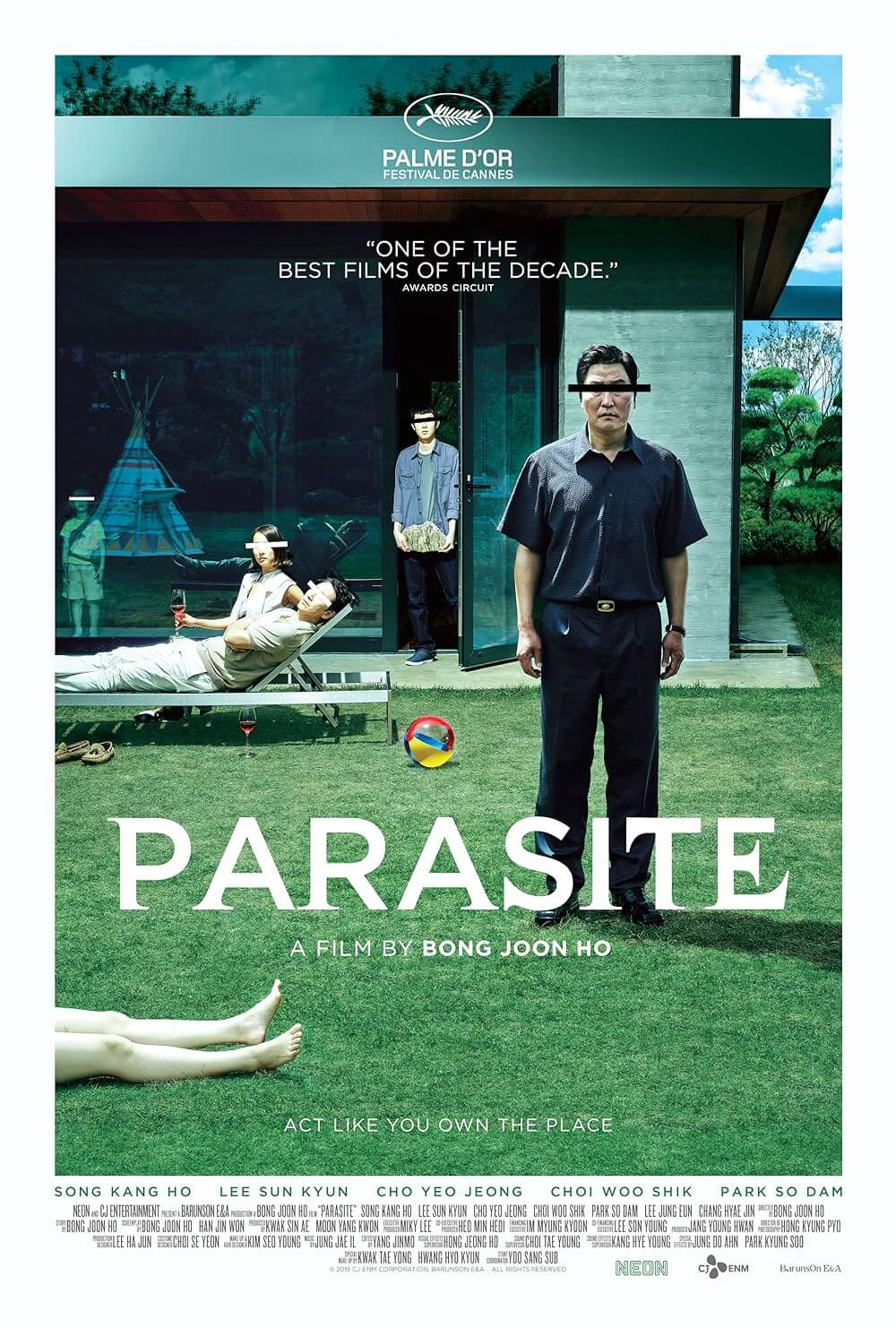

Bong is the film’s writer and director. The South Korean auteur is probably best known in the United States for his four-time Oscar winner Parasite (2019), for which he earned Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature statuettes. However, his breakout film, and many since, have used elaborate science-fiction scenarios to confront matters of capitalism, class inequality, corporate greed, and environmental exploitation. The Host (2006) established his genre-bending approach, blending dark humor, tender family dynamics, and a massive toxic disposal cover-up in a format that both embraced and reinvented the monster movie template. Snowpiercer (2013) considered similar ideas, albeit on a train racing over a post-apocalyptic frozen Earth—a microcosm of social hierarchies. My personal favorite of his films in this mode, Okja (2017), involves a rebel group determined to save an intelligent superpig from becoming fodder for hedonistic factory farmers. Mickey 17 feels aligned with these earlier efforts, almost like a compendium of his preoccupations, except Bong based the film on Edward Ashton’s 2022 novel Mickey7.

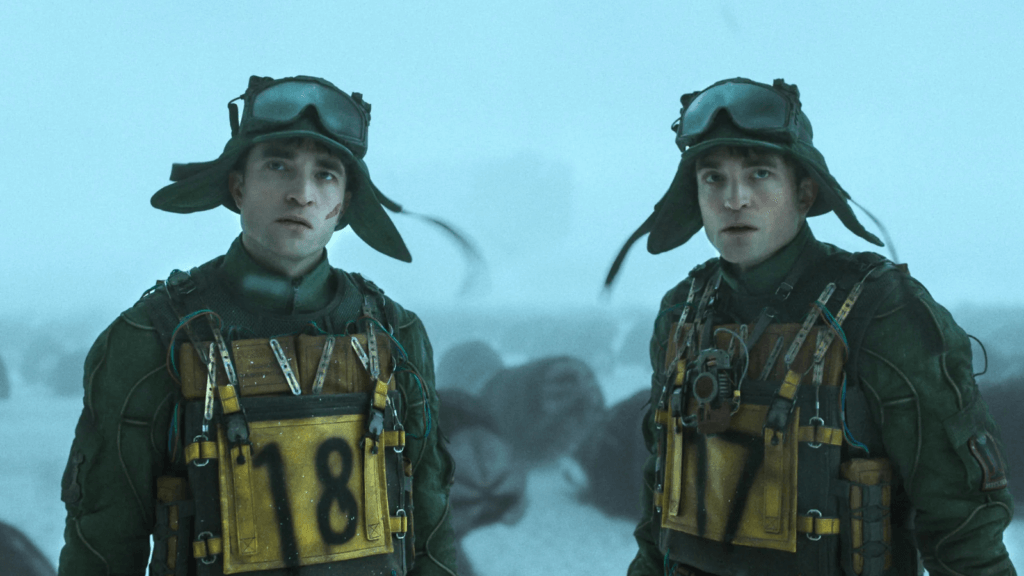

Played by Pattinson in multiple performances, each demonstrating his incredible range, Mickey isn’t the brightest bulb. He gives a cursory overview when explaining the science of cloning and, when he cannot get specific, resolves, “Let’s just say it’s advanced.” He doesn’t bother with technobabble; he doesn’t understand it either. Early in the film, he recounts how he and his friend Timo (Steven Yeun) signed up for the colonizing mission to escape a sadistic loan shark who funded their failed macaroon shop. Signing up for off-world missions has become a common solution for those with money problems in this undated future. Timo trains to become a pilot; Mickey signed up as an Expendable but didn’t read the fine print—that he would be assigned dangerous missions, and when he ultimately died, he would be reprinted. Aboard the spacecraft, Mickey is the lowest rung on the social ladder, though he finds joy with Nasha (Naomi Ackie), a security officer who doesn’t see the titular clone as an ever-degrading copy but rather as an individual. They’re all headed to Niflheim, a snow planet named after the icy Norse realm, which they discover is inhabited by a native animal species.

Although its themes of cloning, colonization, and strange creatures drive the story, Mickey 17 is urgently political, much like Bong’s other work. Most undeniable is Mark Ruffalo’s parodic Trump performance on par with Nicolas Cage in Color Out of Space (2020). Ruffalo plays the megalomaniacal Kenneth Marshall, a failed politician who volunteers to lead the mission to Niflheim—if only to prop himself up as the new human civilization’s Great Man. Ruffalo’s performance compares to Jake Gyllenhaal’s turn in Okja in its sheer outrageousness. But the particulars are pure Trump, complete with unchecked narcissism, absolute stupidity, and feigned strength to hide a fragile ego. His MAGA-esque followers wear red gear featuring his campaign slogan, “One and Only,” accompanied by a Nazi-style salute with an index finger pointed upward. Teamed with an unnamed church that treats him like the second coming, he hopes to create a “pure white planet” where certain choice women will serve as breeders to propagate the species. Marshall’s dialogue is funny and chilling in its familiarity, but it’s less of a parody than a reflector. Toni Collette plays Marshall’s devoted and demented wife, Ylfa, an insidious elitist rooted in her privilege, concerned more with her oriental rugs than human life.

That’s bad news for Niflheim’s local population, demonized as “Creepers” by Marshall. Resembling a cross between a cow and pillbug, they’re poised for extermination, while aspiring saucier Ylfa hopes to blend their tails into a culinary sauce, which she calls “the true litmus test of civilization.” Mickey 17 grapples with how corporations and governments mistreat life in favor of their administrative ambitions, as Marshall and his acolytes ignore clear signs of the Creepers’ intelligence in favor of human dominance. Mickey’s status as a clone of below-average intelligence—the 17th clone, no less—means he’s downgraded humanity. And while he would usually accept death and reprinting, an accident that leaves him at the mercy of the Creepers has unexpected outcomes: First, the Creepers rescue him after he’s left for dead in a frozen Niflheim cave, suggesting they’re intelligent and friendly. Then, when he returns, he finds another version, Mickey 18, has been printed. Now that there are two of them, their individuality and mortality come into question. Mickey 18 isn’t an exact duplicate of Mickey 17, personality-wise; the later edition has an aggressive streak. Nasha describes the two Mickeys as “mild” and “habanero,” and Pattinson reportedly based his performances on Ren and Stimpy.

True to Bong’s style, Mickey 17 has enough material writhing around inside to populate a limited series or much longer film. Compressing its many ideas into a 137-minute feature, Bong delivers the tonally off-kilter experience those familiar with his sci-fi work, or South Korean New Wave cinema in general, will recognize and cherish. The mood often occupies a macabre hilarity informed by Pattinson and Ruffalo’s absurdist performances, yet it’s also full of perilous situations, disturbing details, and a nail-biting finale that pits Marshall’s conceit against the Creepers’ intellect. The film’s radically shifting tenor produces a destabilizing effect, far from tidy, and reflective of our world’s complicated messiness. Bong’s orchestration of these disparate tones into a cohesive narrative that pushes and pulls the viewer in various directions, all by engaging us in individual moments and the larger picture, is a testament to his masterful skill—apparent for over 20 years and re-proven with each subsequent film.

Mickey 17 is an ambitious production, massive in scope and varied in its locations and set pieces. Costing well over $100 million, the film is that characteristically expensive, some might say indulgent production that sometimes follows an Oscar win. Warner Bros. serves as the distributor, giving Bong creative carte blanche and the elusive final cut—a must on his films since he battled with Harvey Weinstein over Snowpiercer’s runtime and won, only for Weinstein to truncate the theatrical release out of spite. While often relying on production designer Fiona Crombie’s terrific practical sets and convincing environments, Bong also deploys plenty of computer-generated visuals to render Mickey’s spacewalks and the Creepers, not to mention the flawless-looking scenes where Pattinson (absolutely fantastic throughout, reminding us that he’s one of today’s most inventive actors) shares the screen with himself. Darius Khondji’s cinematography lends every shot textured details, being well-versed in wild sci-fi stories after his work on The City of Lost Children (1995) and Okja.

What makes Bong’s films such full experiences is that he crams every moment with visual splendor, rich characters, intricate details, and heightened performances to enhance their themes. If Mickey 17 seems chaotic, it is organized chaos in a manner that I love. The film belongs on a shortlist of films, including Brazil (1985), Cloud Atlas (2012), and The Zero Theorem (2013), that seem to be about everything. Its themes prove timeless but also allusive to this moment, when recent events have amplified the world’s collective anxiety over things to come. Nasha, in many ways the empathetic heart of Bong’s story, articulates the film’s ideological frustrations in an angry “F-U” speech to Marshall. I could sense the crowd nodding along and laughing in recognition of her rage over Marshall’s continued bullshit. His fascistic, hypocritical (he limits caloric intake for his staff but eats like a glutton), and comically haughty persona (he and Ylfa have a chandelier in their spaceship quarters) ultimately receives due comeuppance in the cathartic climax, but not before testing the viewer’s dread with a breathless threat to the Creepers.

Mickey 17 feels like the kind of movie that might get banned in a year or two, assuming the US continues down its current spiral. Still, it’s entirely possible to view it as escapist fun—and indeed, I had a blast watching it. The film is enriched further when considered in tandem with its sociopolitical commentary, achieving subtle poignance and over-the-top satire. That’s part of Bong’s appeal: his ability to splice broad ideas with nuanced ones, spectacle-sized entertainment with a pointed message. Watching it, I realized how much I had been starving for an alternative to the usual banal blockbusters and endless recycling of well-established intellectual property. Studio movies like this don’t come along often. They’re usually the product of an ambitious filmmaker given the rare chance to make whatever they want and explore the limits of their imagination. Sometimes, that results in an ambitious failure. Other times, a film like Mickey 17 comes along and reminds us how fun, intelligent, bold, and original even large-scale cinema can still be under an inspired filmmaker.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review