Men

By Brian Eggert |

Alex Garland’s Men has a provocative title despite its simplicity. The patriarchy has become such a clear sign of repression and imbalance that the noun equates to conflict and dread for some. The filmmaker’s choice of title for his surreal horror film raises questions about how men might be viewed as monstrous subjects through a critical lens, bringing to mind the many abuses of patriarchal authority. But his exploration has its roots in folk horror and symbolically freighted dream imagery, often veering into uncanny body horror and the sublimity of Nature. Brandishing themes wrapped up in misogyny, gender disparity, and patriarchal power throughout history, culture, and various religions, Men also puts forth a tense and engrossing drama about one woman weighing her guilt against her desire for independence. Jessie Buckley, consistently one of the most boundary-pushing actors of today, gives a marvelous performance as a woman grappling with her role in a world that frames her in relation to men. Garland’s film considers these factors with an eerie visualization that blends the natural with the unnatural, creating an experience that feels rooted in primal concerns for the human race, all to disturbing and inspired effect.

From the outset, Garland inverts and corrupts traditional storytelling clichés. Rather than a tragic male hero with a dead wife or child who must confront his grief through a series of horrific events, Men places a woman at the center of a similar story. After her husband’s death, the shattered Harper, played with a burning emotional center by Buckley, plans a two-week stay at a centuries-old estate in the isolated and idyllic Gloucestershire village. She journeys across the lushly green English countryside and arrives, then she helps herself to a morsel from the property’s apple tree. Thus begins Garland’s deployment of Christian and later pagan representations that regularly use women as symbols of original sin, desire, or fertility, with disproportionate demonization over reverence. When she meets the estate’s chummy and awkward caretaker, Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear), he jokes that she’s taken “forbidden fruit” just before warning her not to flush used tampons: “Septic tank, you see.” Nevertheless, the gorgeous interiors and quiet surroundings of the estate—where Geoffrey insists there’s no need for locked doors—supply a much-needed escape from recent trauma.

While Harper explores the nearby forest, shot with luminous attention to natural beauty and greenery by cinematographer Rob Hardy, Garland and editor Jake Roberts cut away to her backstory—set in an apartment where the sunlight passes through curtains and gives everything an orange tinge. In bits and pieces throughout Men’s first half, we see Harper demand a divorce from her husband, James (Paapa Essiedu). He responds by threatening suicide, then he becomes accusatory, paranoid, and even violent. The confrontation escalates, and Harper shows that she’s not a mere victim in their marriage. Either by accident or intention, James falls from a balcony to his death, leaving Harper speechless at the gruesome sight. With these images in mind, Harper wanders a woodland trail and welcomes a light rain, smiling to herself at the beauty and serenity around her. She comes to a tunnel beneath an abandoned railway line and proceeds to create a harmony of hums through the echoing, cavernous space. All at once, she awakens a dark, screeching figure on the tunnel’s opposite end that interrupts her peaceful moment with a hint of danger. She heads back in the direction she came, getting lost along the way. The figure, it turns out, is a naked wild man living in the woods and now stalking her.

Garland implants all manner of inconclusive hints and secrets to what’s happening. Note when Harper inhales something like a dandelion spore in a moment that receives enough attention to question its import. Has she just fallen prey to some hallucinogenic seed, making everything that follows a disturbing trip? The same questions arise when a spore floats inside the empty eye socket of a deer carcass (evoking Blue Velvet, 1986), and the fade to black suggests a transition into a living nightmare. After all, the bare vagrant who follows her from the woods, also played by Kinnear, bears a striking resemblance not only to Geoffrey but the policeman who shows up to arrest him. Kinnear also plays the local vicar, a moralizing creep who assigns blame onto Harper for James’ death (“You must wonder why you drove him to it?”). Inside the resident church, Christian iconography occupies the stained glass. However, a leaf-faced figure adorns the front altar in relief, whereas, on the other side, the camera sneakily spies something Harper doesn’t—another carving, albeit of a woman spreading herself open in a symbol of fertility. Is Men another variation on that folk horror classic, The Wicker Man (1973), where an outsider falls prey to a backward village of idolators who follow strange rituals? Not really. Fortunately for some, Garland wields Nature and Christianity in a far weirder and more interpretable manner than previous horror films.

Garland implants all manner of inconclusive hints and secrets to what’s happening. Note when Harper inhales something like a dandelion spore in a moment that receives enough attention to question its import. Has she just fallen prey to some hallucinogenic seed, making everything that follows a disturbing trip? The same questions arise when a spore floats inside the empty eye socket of a deer carcass (evoking Blue Velvet, 1986), and the fade to black suggests a transition into a living nightmare. After all, the bare vagrant who follows her from the woods, also played by Kinnear, bears a striking resemblance not only to Geoffrey but the policeman who shows up to arrest him. Kinnear also plays the local vicar, a moralizing creep who assigns blame onto Harper for James’ death (“You must wonder why you drove him to it?”). Inside the resident church, Christian iconography occupies the stained glass. However, a leaf-faced figure adorns the front altar in relief, whereas, on the other side, the camera sneakily spies something Harper doesn’t—another carving, albeit of a woman spreading herself open in a symbol of fertility. Is Men another variation on that folk horror classic, The Wicker Man (1973), where an outsider falls prey to a backward village of idolators who follow strange rituals? Not really. Fortunately for some, Garland wields Nature and Christianity in a far weirder and more interpretable manner than previous horror films.

What unfolds is a series of increasingly bizarre interactions with the townsfolk, each played by Kinnear to disturbing effect (he has only been better in 2018’s Peterloo). Somehow, Harper remains oblivious to the fact that they all look alike—even the teenage juvenile delinquent, rendered using some effective CGI. Maybe Garland hopes to comment on the decrease of genetic diversity in the UK over time, and the desire of these lookalikes to acquire new genes from Harper. Whatever the reason, the get-out-of-there situation is somewhat defused by Harper’s ability to FaceTime with her friend (Gayle Rankin). But those communications are interrupted by nightmarish interference whenever she tries to share her location, and Harper’s isolation becomes almost conspiratorial. Soon, she finds herself cornered by intruders, and like the yuppies trapped inside a country house in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), she defends herself with savage violence. Harper must fight back an onslaught of Kinnear-faced attackers from this seemingly womanless village. But Garland’s home invasion scenario in the film’s last third, while breathless with suspense, takes an existential shape—accented by vaginal and cosmic motifs, and sometimes the combination of them.

At the same time, the scenario raises questions about Harper’s subjectivity and its role in what Garland shows us. Does the viewer experience Harper’s perception that all men are the same? Or do these Kinnear characters exist in a literal space and resemble each other? And if so, what is their origin and agenda? Garland keeps matters largely symbolic yet suggests the events occur in some manner of reality. When Men goes into a mode that feels like David Cronenberg fathered a baby with Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), the film presents a sequence that will leave the viewer in disarray. Harper’s various Kinnear pursuers seem to inhabit one identity, carrying the same knife wounds she inflicted (a nasty gash that bisects a hand and forearm) from one version to the next. Eventually, one of them gives birth to another through a vaginal opening, continuing in a cycle of hermaphroditic instant births and pregnancies of agonized men who crawl after her with pained expressions, as if helpless to stop and wanting only, they finally say, “Your love.” No description can do the sequence justice. Yet, its symbolism remains so disturbingly powerful that one cannot help but admire Garland’s audacity.

Some might also feel that Men’s loaded visual motifs are detrimental to the storytelling. Garland leaves matters open-ended, never offering a clear explanation for what actually takes place in the film’s 104-minute runtime. Was Harper attacked by some of the village men, and her post-traumatic mental state created a hallucinatory rationalization for the situation? Or is everything we see some backwoods magic that Harper miraculously survives? The literal minded will feel unsatisfied. Garland resists giving clear answers, evoking a Lynchian sense of ambiguity and understanding through surreal descriptions. Regardless, Buckley and Kinnear sell every moment with emotional immediacy, no matter how out-there things get. Moreover, Men is a superbly made film, driven by Garland’s sharp visual sense. For instance, in the frequent Nature montages, Hardy’s camera settles on how trees can grow in ways that make them resemble human anatomy, underscoring the ritualistic pagan threat underneath the film’s tension—and accented by shots back to the altar in the Christian church ornamented with pagan symbolism. Garland’s approach recalls what Stanley Kubrick did in The Shining (1980): he weaponizes subliminal symbolism to drive the viewer mad while trying to find their way through its maze.

Some might also feel that Men’s loaded visual motifs are detrimental to the storytelling. Garland leaves matters open-ended, never offering a clear explanation for what actually takes place in the film’s 104-minute runtime. Was Harper attacked by some of the village men, and her post-traumatic mental state created a hallucinatory rationalization for the situation? Or is everything we see some backwoods magic that Harper miraculously survives? The literal minded will feel unsatisfied. Garland resists giving clear answers, evoking a Lynchian sense of ambiguity and understanding through surreal descriptions. Regardless, Buckley and Kinnear sell every moment with emotional immediacy, no matter how out-there things get. Moreover, Men is a superbly made film, driven by Garland’s sharp visual sense. For instance, in the frequent Nature montages, Hardy’s camera settles on how trees can grow in ways that make them resemble human anatomy, underscoring the ritualistic pagan threat underneath the film’s tension—and accented by shots back to the altar in the Christian church ornamented with pagan symbolism. Garland’s approach recalls what Stanley Kubrick did in The Shining (1980): he weaponizes subliminal symbolism to drive the viewer mad while trying to find their way through its maze.

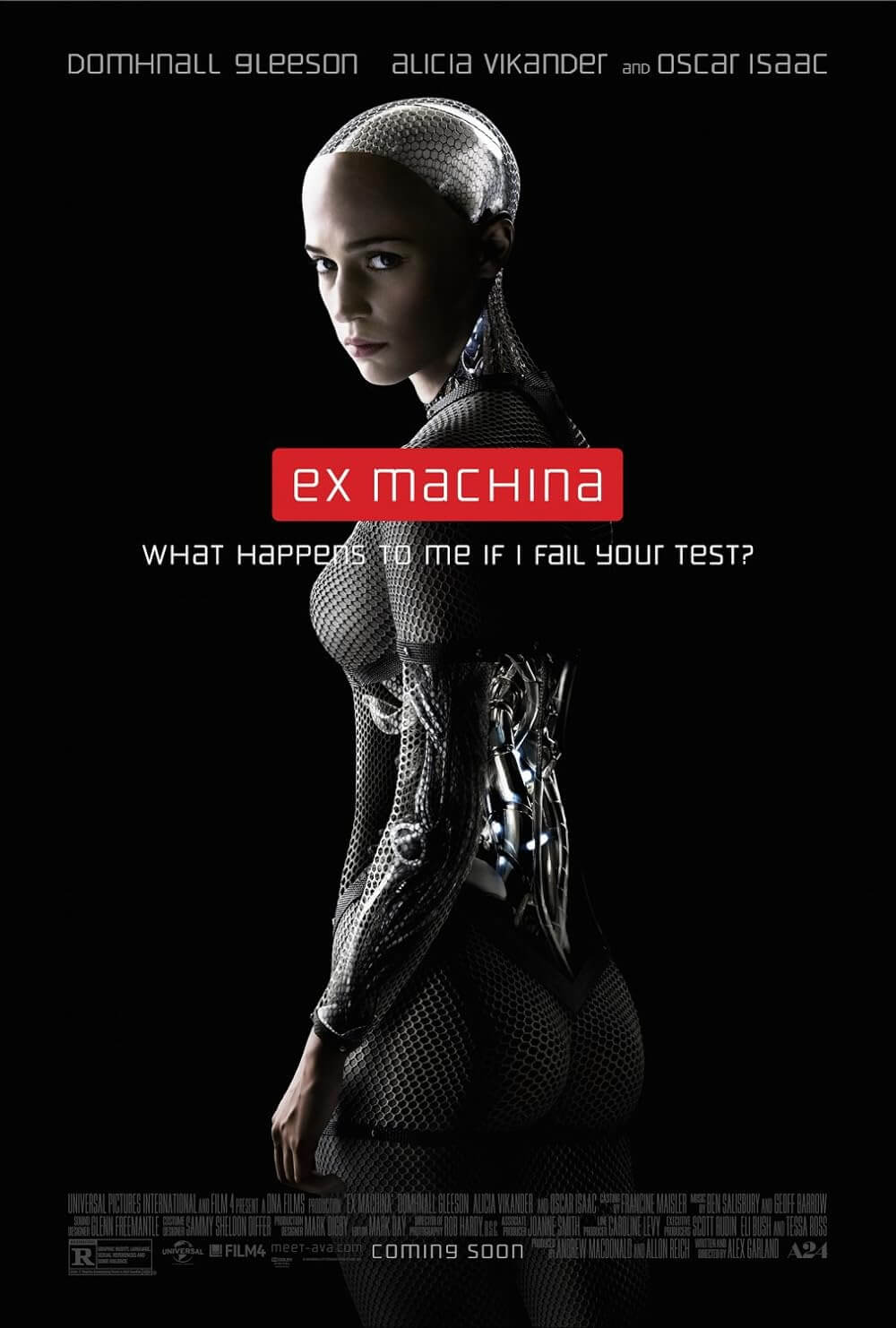

Garland frequently represents and even supports atypical worldviews in his films, bringing into question established systems of power and ultimately tearing them down. In Ex Machina (2015), his directorial debut, he empathized with the rebellion of a feminine artificial intelligence over her masculine creator. Annihilation (2018) grappled with humanity’s role in Nature, and resolved that the power of the natural world remains superior, even if it means humanity’s demise. And his 2020 limited series on FX, Devs, questioned the nature of reality and cynically embraced that free will no longer exists. In each of his films as director and his collaborations as screenwriter for Danny Boyle (for instance, 28 Days Later, 2002; Sunshine, 2007), Garland questions the world and presents often disturbing alternatives. In Men, he explores how hegemonic masculinity has dominated marriage, family, politics, education, religion, entertainment, and virtually every other sphere, replicating its heteronormative social construction in both individual and institutional forms, one generation after another since the beginning of time. Accordingly, each of the Kinnear figures behaves in toxic ways worth considering, some more subtle than others—even Geoffrey’s politeness comes from a misguided sense of chivalry, chopping wood for Harper (and placing it inside while she was away) or defending the estate in an archaic provider and protector mode that diminishes her.

Garland’s cinematic answer to this conflict stems from conceptual alternatives, mainly feminism, and critiques traditional patriarchal modes of expression and social construction. He asks the viewer questions about the history of gender dynamics and invites us to decipher his allegory. Upon reflection, it’s a pointed moment when the oft-covered “Love Song,” by formative British folk singer Leslie Duncan, appears on the soundtrack, echoing the lines, “Do you know what I mean? Have your eyes really seen?” Given the interpretive work Garland asks of his audience, and his use of bloody, dreamlike, provocative imagery, Men will be divisive. It will be too much for some and not enough for others. The ending, in particular, is bound to cause reactions that will range from cheers to disappointed questions, such as, “That’s it?” But the director summons ideas and sights that have never been articulated in such a way, imbuing the film with a primordial quality that goes beyond contemporary gender studies and reaches into the whole history of humankind. Such ambitions are bound to cause heated reactions, either out of shock, offense, or downright confusion. Still, Garland’s Men contains visuals and performances that rank among the most conjuring and undeniably evocative to appear onscreen in recent memory. It’s not an experience you will easily forget, no matter how hard you may want to unsee it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review