Memory: The Origins of Alien

By Brian Eggert |

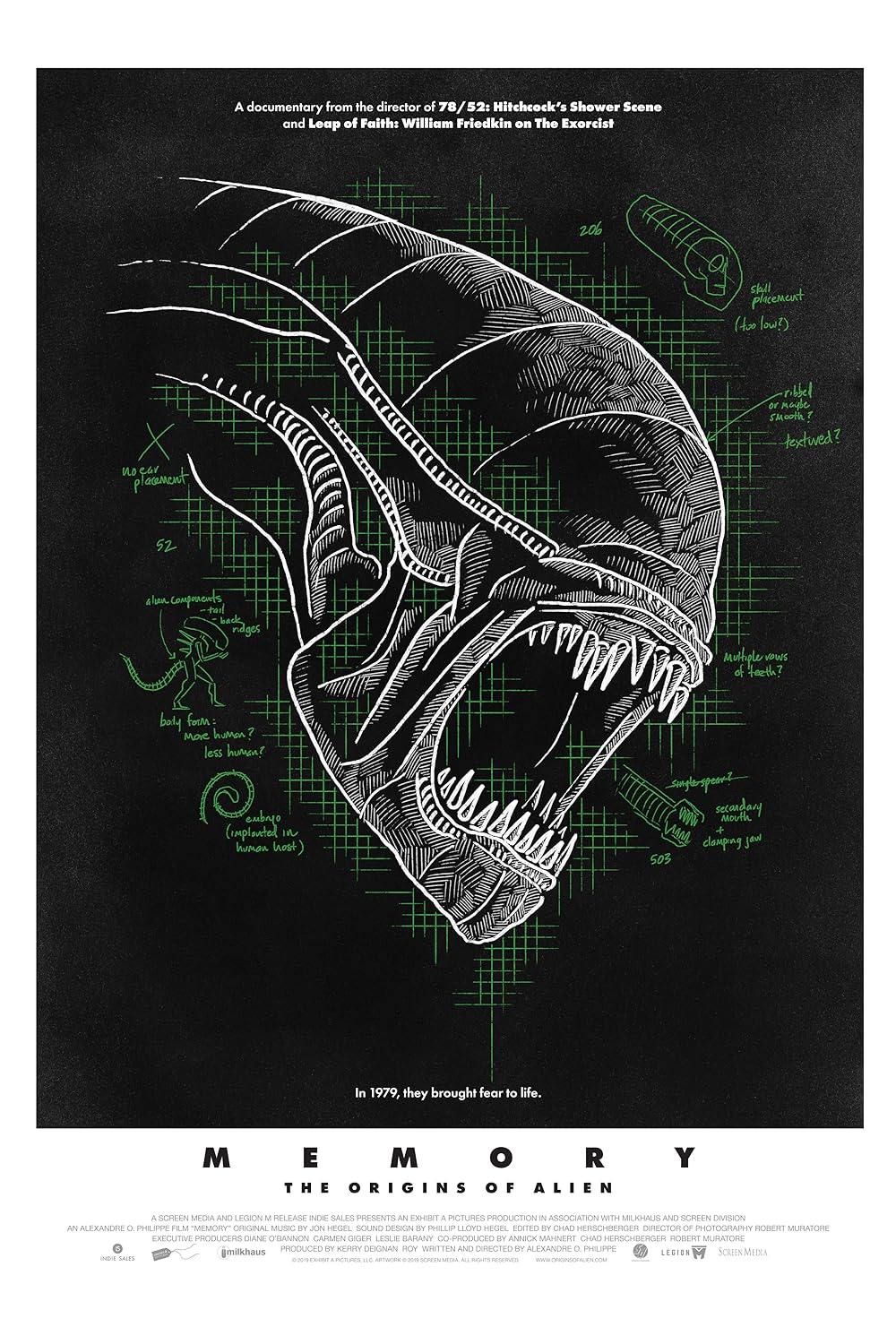

Just when you thought it was impossible to love a film any more than you already did, along comes Memory: The Origins of Alien, Alexandre O. Philippe’s latest documentary of film appreciation. Taking the video essay and expanding the medium to the equivalent of a full-fledged thesis project, Philippe makes a series of well-reasoned arguments about Ridley Scott’s Alien from 1979. The formative blend of science-fiction and horror has been a favorite of this writer since childhood when early viewings supplied a lifetime of nightmares and fascinations with similarly themed material. But Philippe plunges into the conscious and unconscious influences on the film’s authors, namely Scott as director, Dan O’Bannon as writerly womb, and H.R. Giger as the designer responsible for the xenomorph design. Although Memory touches on aspects such as the performances and the film’s place in genre filmmaking, the documentary shines in its anatomy of the legendary chestburster scene, its symbolism, masterful construction, and reflexive ability to access our innermost fears.

Far from a making-of documentary, the sort better suited for those featurettes on a physical media that were so popular in previous decades, the film also resists a purely academic perspective. Philippe, both an avid cinephile and a skilled filmmaker, penetrates his subject in a way that argues a clear line of thinking about Alien. It’s a film that makes several arguments about Scott’s masterpiece, reaches into history, cultural analysis, and interviews to find evidence, and then weaves its ideas together with clear-minded cohesion. The centerpiece is the famous scene in which John Hurt, surrounded by his crewmates at the dinner table, suddenly begins to convulse, until a small, penis-shaped creature explodes from his chest cavity. It’s a scene that shocked the cast and crew almost as much as it shocked, and still shocks, viewers. Flowing into this unforgettable moment of cinema are all manner of influences, some of them unspoken by the filmmakers yet evidenced in Philippe’s study.

Philippe has carved out a small niche for himself as the writer and director of movie buff documentaries. It’s a subgenre of non-fiction filmmaking that can sometimes resort to empty fandom and appreciation. Philippe’s work rises above the shallow competition by providing thorough histories and thoughtful analyses, usually aimed at the horror genre. He first gained attention with The People vs. George Lucas (2010), an examination of fandom gone awry, as followers of the Star Wars franchise turn on its creator (one wonders if Philippe will return to the subject in the post-Disney Star Wars continuum). Next came Doc of the Dead (2014), telling the story of the pop-culture zombie, from its origins in myth, then to George A. Romero, and leading up to The Walking Dead. Most recently, his fascinating 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene (2017) considered the iconic moment in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) when Marion Crane is stabbed to death over 78 setups and 52 cuts. If nothing else, Philippe’s body of work represents a sort of film-school-at-home for viewers either enthusiastic about his chosen subjects or interested in learning more.

Memory opens with a curious visual association between the Temple of Apollo in Greece, where stone carvings resemble the diagrams of future technology, and a gradual transition into the mechanical interior of Alien’s blue-collar spaceship, the Nostromo. From here, Philippe creates an expressive, haunting image of three silver-toothed Furies emerging from beneath a blue laser-line, like the one found in the film’s egg chamber. This image may seem abstract and strangely out of place, until about 95 minutes later when Philippe brings these concepts together, having convincingly argued that Alien is a story born from the “ancient past,” drawing from the innate fears of its creators and perhaps all artistic creation. As the documentary proceeds, it engages in other visually stimulating approaches, such as stock footage shown on monitors that recreate the look of the Nostromo’s interior. The interviewees, including some of the cast and crew (Sigourney Weaver and Ridley Scott are conspicuously absent), appear against dark backdrops for a moody yet consistent aesthetic. This is a beautifully made documentary, whose visual approach never resorts to arbitrary choices.

Memory opens with a curious visual association between the Temple of Apollo in Greece, where stone carvings resemble the diagrams of future technology, and a gradual transition into the mechanical interior of Alien’s blue-collar spaceship, the Nostromo. From here, Philippe creates an expressive, haunting image of three silver-toothed Furies emerging from beneath a blue laser-line, like the one found in the film’s egg chamber. This image may seem abstract and strangely out of place, until about 95 minutes later when Philippe brings these concepts together, having convincingly argued that Alien is a story born from the “ancient past,” drawing from the innate fears of its creators and perhaps all artistic creation. As the documentary proceeds, it engages in other visually stimulating approaches, such as stock footage shown on monitors that recreate the look of the Nostromo’s interior. The interviewees, including some of the cast and crew (Sigourney Weaver and Ridley Scott are conspicuously absent), appear against dark backdrops for a moody yet consistent aesthetic. This is a beautifully made documentary, whose visual approach never resorts to arbitrary choices.

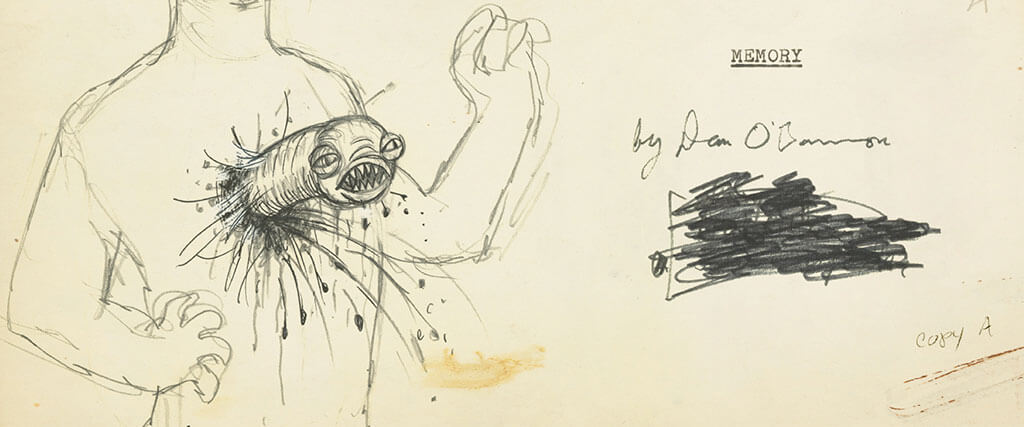

The doc begins with O’Bannon, a true maverick, who conceived of Alien after a lifelong fascination with science-fiction, a fear of insectoid creatures, and his own bodily anxieties. Philippe cites O’Bannon’s influences from H.P. Lovecraft to the Atomic Age movies such as It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958), Planet of the Vampires (1965), and Queen of Blood (1966), as well as an obsession with parasitic wasps that implant their eggs in unwilling hosts. His brief collaboration with Alexandre Jodorowsky on the aborted production of Dune, on which Giger was a designer, also influenced the outcome of Alien. After charting some of the film’s behind-the-scenes development from a series of lingering preoccupations in O’Bannon’s head to a full-fledged production at Twentieth Century Fox, Philippe weighs the influence of Egyptian visual schemas, Francis Bacon, and Joseph Conrad. The interviewees also draw comparisons between Scott’s approach and that of Stanley Kubrick. Perhaps the most relevant line of thinking comes from Clarke Wolfe’s impassioned belief that Alien is about the “accidental awakening of the repressed feminine,” in which the guilt of a patriarchal society comes to life in the form of a deadly xenomorph.

But rather than engage in further spoilers—a curious concept for a documentary—and recount every connection and claim made here, this review will let you discover Philippe’s line of reasoning for yourself. Suffice it to say, Memory: The Origins of Alien is easily Philippe’s best film. The commentaries and theories discussed therein establish the chestburster scene as a pivotal moment in film history, which we already knew, but the documentary’s thoughts about this moment enhance the familiar. It makes you want to rush out and watch Alien again, for the millionth time, and see things that you may never have considered. Like the best appreciations of cinema, the documentary gives the viewer a new understanding of the texts and extra-texts at work in a timeless film. By no means an all-inclusive study of every plot detail or source, the doc reminds us that no work of cinema, especially not one as brilliant as Alien, is a closed text. “I don’t think we can get to the bottom of Alien,” says one of the interview subjects. True, but Philippe has given the most devoted fans reason to revisit it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review