Memoirs of an Invisible Man

By Brian Eggert |

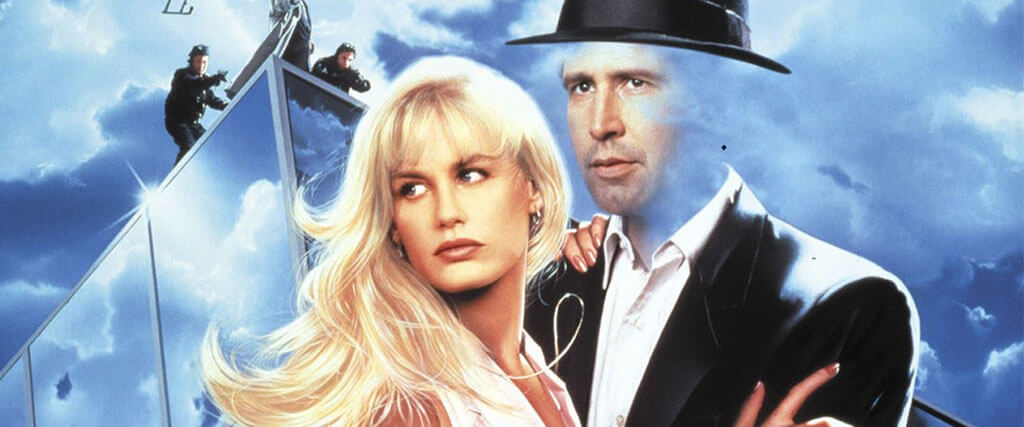

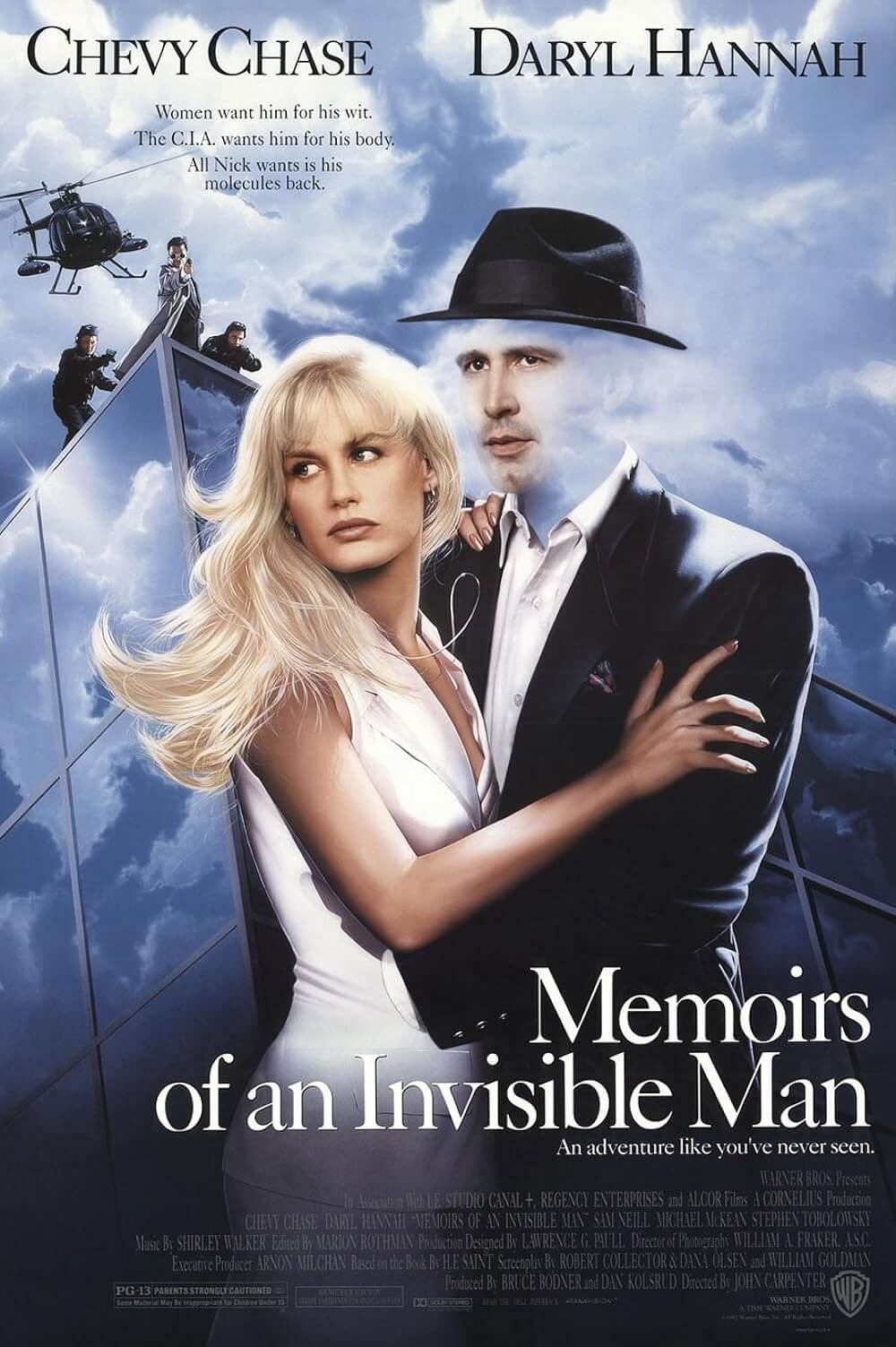

Memoirs of an Invisible Man fulfills neither the promise of a Chevy Chase vehicle nor becomes what audiences envision when they think of a film by director John Carpenter. An unlikely blend of existential metaphors, romance on the run, noirish voiceover punctuated with dry humor, science-fiction concepts backed by impressive special FX, and a playful high-stakes yarn reminiscent in tone of North by Northwest or To Catch a Thief, the film is something altogether unique. However, it’s not what one expects from either Chase or Carpenter; it’s a spy-thriller in Alfred Hitchcock’s lighter, 1950s style. Berated by critics and shrugged off by fans of both the actor and director upon its release in 1992, the film defies the contract signed between Hollywood and moviegoers—a contract that details how the starring talent is supposed to behave, how the director’s films are supposed to look, and how such talent is supposed to make us feel. Despite being a commercial release from Warner Bros., Memoirs of an Invisible Man resists conventionality, even while being entirely accessible and entertaining.

The film was based on the darkly comic novel by H.F. Saint, published in 1987. Saint used the familiar veneer of H.G. Wells’ classic text The Invisible Man, and further, James Whales’ 1933 adaptation for Universal, as the foundation for a critique of 1980s excess. Much as Bret Easton Ellis would use murderous impulses as an allegory for a similar theme in 1991’s more popular American Psycho, Saint used his protagonist’s central hangup, invisibility, as a symbol for the cold and empty interior world of the prototypical businessman of his decade. The novel’s anti-hero is a self-absorbed Wall Street trader, Nick Halloway, who conducts business over the phone and maintains no real relationships. His eventual invisibility in a freak accident becomes a slick metaphor for his social nonexistence, reflected in the ease at which he’s able to continue living in spite of being visibly challenged. However, stricken with both physical and psychological transparentness, the character must engage in an ironic assessment of self.

Screenwriter William Goldman (All the President’s Men, The Marathon Man) adapted the material for director Ivan Reitman (Ghostbusters) at Warner Bros., with Chase’s production company guiding the project’s development. But Chase, wanting to change his onscreen persona and demonstrate that he could do more than comedy, insisted on toning down the humor. He wanted to put as much distance as possible between himself and his image as Clark W. Griswald of the National Lampoon’s Vacation franchise or his image as the pratfalling Saturday Night Live buffoon. Chase sought Robert Collector and Dana Olsen to rewrite the script, and at the time Richard Donner (Lethal Weapon, 1987) was attached to direct. When Donner backed out, Carpenter was hired in a journeyman capacity and expected to deliver the same outcome as Starman in 1984: a crowd-pleasing effort with dazzling special FX and a touch of romance. The resulting film had more humor than Chase would have liked, less romance and social relevance than Carpenter would have desired, but it’s filled with memorable set-pieces and charming moments with its cast.

The story, structured like a film noir, opens on the invisible Nick Halloway (Chase) documenting his story on videotape for reasons that become evident later. Living as an affirmed bachelor, one night Nick meets Alice (Daryl Hannah), a TV producer, and falls in love. But the next morning, hung over and tired, he sleeps through a shareholders’ meeting at Magnascopic Laboratories, where he’s turned transparent after a mysterious accident. Enter CIA operative David Jenkins (Sam Neill), who, upon learning that the Magnascopic building turned invisible, becomes obsessed with locating Nick—the one man inside during the accident—and exploiting his see-through state for nefarious, off-the-books espionage. On the run and barely coping with life as an imperceptible being, Nick secludes himself before turning to Alice. She helps him evade exposure and come up with a plan to escape Jenkins, while they also fall in love. Meanwhile, Jenkins tries to strong-arm both the scientist (Jim Norton) who inadvertently caused Nick’s condition, while simultaneously betraying the trust of his superior (Steven Tobolowsky), all for the chance to become the handler of an invisible agent—an acquisition he’s willing to kill for. Jenkins kidnaps Alice to draw out Nick. During a final showdown, Nick kills Jenkins and rescues Alice, while making it appear as though he died in the process. Nick and Alice disappear, living their lives in isolation.

Sometimes, when a film doesn’t fit into a familiar, easily consumable package, viewers respond by rejecting and condemning it for betraying their trust in a proven formula. Unsure of how to consume Memoirs of an Invisible Man, as either a Chevy Chase comedy or a John Carpenter fantasy, both audiences and critics responded with confusion and disappointment. Though it was made for over $40 million, the film earned just over $14 million. Notices in the critical community were equally cruel to this certified bomb. Owen Gleiberman, in Entertainment Weekly, wrote the film “comes disappointingly close to being just… another rinky-dink Chevy Chase comedy.” And while many critics offered praise for Carpenter’s confident direction and the superb special FX, Roger Ebert’s rather ungrammatical remark, “we couldn’t care less,” summarized the consensus. Even Carpenter critiqued the film, claiming he sought to capture the social relevance of Saint’s novel but “didn’t quite pull it off.” He calls the film a “noble failure,” perhaps looking at the finished product as a series of creative compromises.

Granted, Carpenter was forced to make cuts during the audience preview process, which eliminated scenes the director felt belonged or gave the film an edge. It was, after all, a studio picture, far removed from his two previous releases—the director enjoyed creative control on Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988), both produced by his production company Alive Films and distributed through Universal. Although it’s tempting to blame Warner Bros. for not granting Carpenter final cut, which accounts for the absence of the usual “John Carpenter’s” above the title, for the first time the director would come to question his desire to work in Hollywood, a system that denies his vision and curbs his artistic authority. And yet, though Memoirs of an Invisible Man is not the film either the studio or Carpenter wanted, with expectations appropriately adjusted, its craft and imagination remain consistently engaging, while its themes have more in common with Carpenter’s work than a superficial glance reveals.

Even harsh critics during its initial release agree that Memoirs of an Invisible Man boasts incredible special FX. Carpenter and his crew pioneered a new, early use for CGI to render believable invisibility, requiring a reported nine months of pre-production time. To achieve the effect, Chase wore a blue bodysuit, and each scene involving the effect was shot twice—once to capture Chase’s movements in the blue getup and a second time to catch what was behind him. Later, effects artists digitally removed Chase from the scene, leaving his outline to appear in, say, a waft of smoke or, in a particularly beautiful sequence, a downpour of rain. The extra effort was worth it, as the innovations became standard practice in Hollywood over the subsequent years, as evidenced in virtually every film with an invisible character or in which a fully appendaged actor plays a character missing a limb (Forrest Gump, for instance).

Drawing from surrealists such as Salvador Dali and René Magritte, Carpenter explored the limits of the effect, capturing images comprised of positive space and the negative gaps in that space. The appearance of the faceless Nick Halloway in a fedora evokes Magritte’s series of paintings of faceless men in bowler hats. The Belgian painter meant his series on well-dressed men with obscured faces as a commentary on the visible, superficial symbols (hat, overcoat, necktie, etc.) that signify a so-called professional, while his true identity, his face, remains hidden. Carpenter offers a distinctly 1980s version of that image: an invisible Nick running on the beach in cross-training gear or on the tennis court practicing his swing in his white yuppie polo and sweatbands. The film’s amusing critique of yuppie culture also includes laughable portraits of desperate well-to-do men—portrayed by Michael McKean and Gregory Paul Martin—trying to grapple with their own misguided attempts at masculinity. Elsewhere, Carpenter savors clever in-camera effects—old-fashioned tricks and plenty of homages to Whales’ The Invisible Man, including a memorable unbandaging sequence, doors that swing shut, and Neill acting as though he’s being held at gunpoint (though in reality, a prop gun has been strapped to him).

At the same time, Carpenter alternates between moments where the audience sees Nick in his invisibility when others cannot and moments where he remains invisible to us. They seem to be chosen at random, alternating without patter, and yet, Carpenter’s choices make the most of both the special FX and Chase’s performance. When Nick is invisible, we swear we can see, or at least envision, Chase’s performance, whereas scenes in which Chase appears onscreen build the character—in particular, when Nick must keep quiet as his friends speak ill of him, and the actor’s expressions contain wounded incredulity. Invisibility in these scenes is more than just a neat visual trick; the narrative device allows Nick to self-assess after seeing how other people see him. As he realizes that his friends find him shallow and elusive, a non-person to whom a bond is impossible, he understands why “for years women have been telling me they could see right through me.” The film’s central irony is unsubtle but effective. Nick may not completely break free of his invisibility by the end; he remains physically transparent and, while he has opened himself up to the experience of a long-term relationship with the now-pregnant Alice, he still hides from the world on their secluded mountainside chateau. Of course, their choice to live in seclusion is one of necessity and survival, not of existential isolation. After all, Nick has committed himself to Alice, and that’s a step in the right direction.

But Memoirs of an Invisible Man has more in common with the typical “John Carpenter film” than the critical consensus or even Carpenter’s own view of the film implied. Nick remains an outsider like so many of Carpenter’s best characters, including Laurie Strode from Halloween, Snake Plissken in Escape from New York and L.A., MacReady in The Thing, Arnold in Christine, the titular alien character in Starman, Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China, Nada in They Live, and Desolation Williams in Ghosts of Mars. Similar to many of those characters, Nick faces a strange and unknown threat that he must meet to overcome the film’s conflict. By confronting the unknown, Carpenter’s heroes or anti-heroes discover their essence and thus demonstrate their true selves. Nick, then, proves outwardly shallow; although, after looking hard enough, a person may find evidence of a human being.

As noted, most of the criticism about Memoirs of an Invisible Man center on the film not living up to what it was supposed to be, with Chase’s onscreen presence being a prime offender. Chase’s sarcasm as Nick should not be mistaken for the dryly comic routine that served the actor’s Irwin R. Fletcher or other comic characters so well; rather, his performance reflects the empty, acerbic quality of Nick Halloway. Our hero doesn’t leap from one wacky situation to the next, allowing for comic hilarity in the process. He is chased by Sam Neill’s expertly portrayed villain, and he feels beleaguered, persecuted, and haunted throughout the film, until Neill’s seedy agent finally meets his demise. Fortunately, the film avoids turning Nick into an invisible prankster, a power-mad despot, or a creepy voyeur (as Kevin Bacon’s invisible mad scientist becomes in Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man from 2000). His cynical sense of humor aside, Nick remains angst-ridden and defined by his loneliness, which, contrary to Carpenter’s own feelings about his film, presents the character as a multi-dimensional protagonist who must reevaluate his lifestyle given his newfound state.

Upon closer reassessment, and from a perspective that frees both the material and its talent from the expectations usually required of them, Memoirs of an Invisible Man provides a thoroughly entertaining and technically accomplished production that has been unfairly maligned over the years. Shot by cinematographer William A. Fraker in bold set-pieces singed by lens flares, the film looks sharp, especially with its still-impressive effects, which later uses of invisibility CGI could not match. Shirley Walker (Batman: The Animated Series) provides a stirring score that lends the material a certain grandiosity and fantastical edge, while set designer Rick Simpson conceives of an inspired set when Magnascopic Laboratories turns into a puzzle of positive and negative spaces. The film may also serve as proof that Hollywood limited the potential of Chase’s talent by saddling him to dull comedies in the years to come. Consider this a call for audiences to revisit Carpenter’s least appreciated work, a charming blend of romance and Hitchcockian thrills, featuring incredible special FX, light humor, a mild social commentary, and accomplished filmmaking.

Bibliography:

Boulenger, Gilles. John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. Spakenburg: H.O.M. Vision, 2002.

Cumbow, Robert C. Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc.; Second Edition, 2000.

Grant, Barry Keith. “Disorder in the Universe: John Carpenter and the Question of Genre.” The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, edited by Ian Conrich et al. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004, pp. 10-20.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Films of John Carpenter. Jefferson: McFarland, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review