Memoir of a Snail

By Brian Eggert |

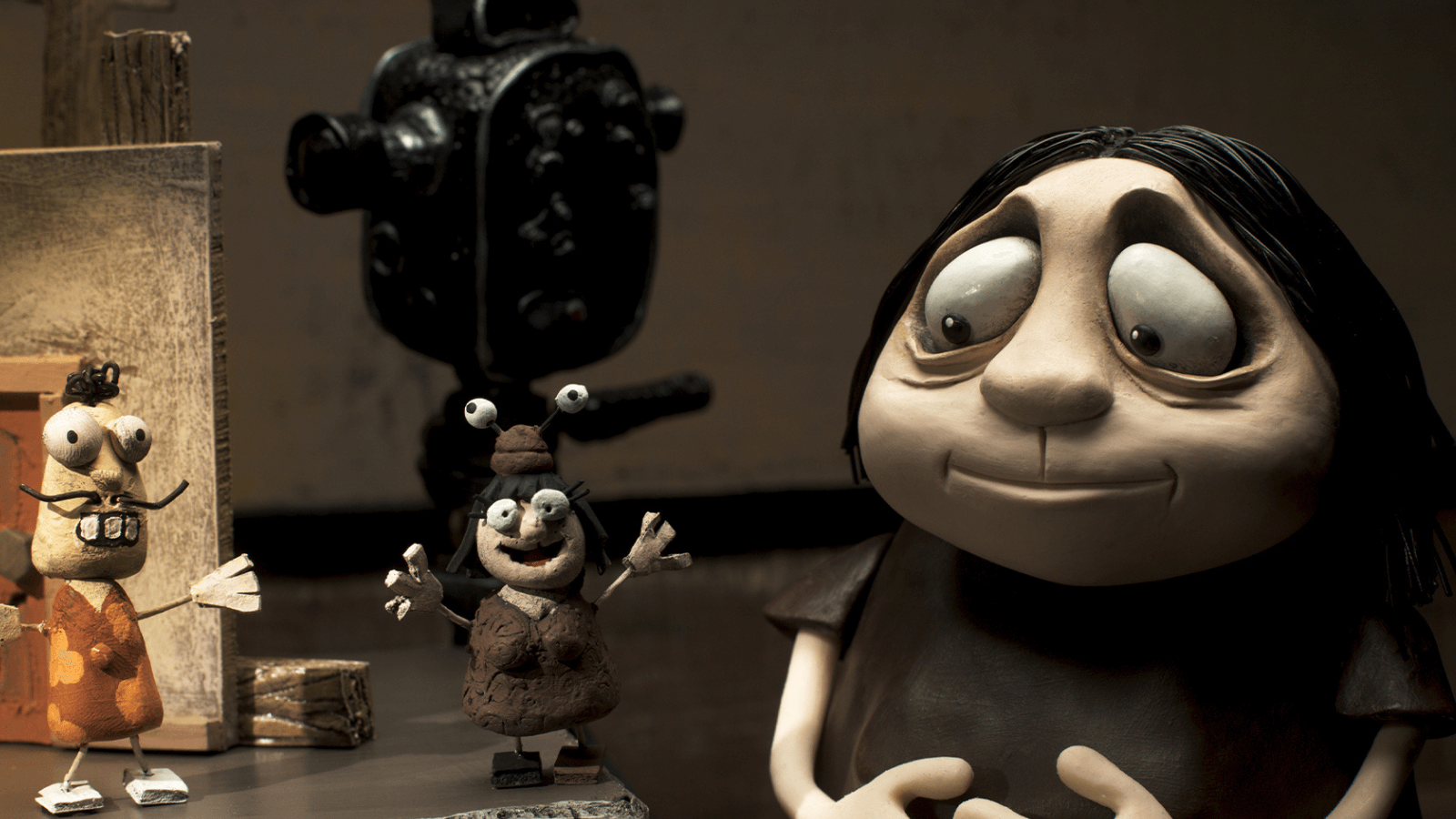

Australian stop-motion animator Adam Elliot doesn’t shy away from difficult subject matter. His latest film grapples with death, isolation, pyromania, depression, religious extremism, bullying, eating disorders, hoarding, fetishism, and public masturbation, among other behaviors. Memoir of a Snail may be animated, but Elliot reminds us that form doesn’t determine content. This is evidenced early on when Pinky (Jacki Weaver), an unapologetically rambunctious woman with dementia, dies after uttering her last words: “The potatoes!” What might seem a random and strangely funny detail gives way to a personal account by the film’s narrator, Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook), Pinky’s introverted young friend who shares her own life story. Elliot assembles a film of a million fastidious hand-crafted details, spinning a yarn containing profound wisdom and humanity. Venturing into a dark arena of eccentricity and morbidity, which makes an obvious counterpart such as Tim Burton—or, more to the point, Henry Selick—seem tame by comparison, the film resonates all the more for its peculiarities and personality.

Though Elliot has made only one other feature, his clearly defined aesthetic and thematic interests remain unmistakable. Back in 2003, he made a short film called Harvie Krumpet that earned him an Oscar and the chance to make his first feature-length project. Six years later, he delivered Mary and Max, a tender story about a young misfit (Toni Collette) who sends a letter to a random address and begins a pen pal relationship with an older man (Philip Seymour Hoffman). With notes of Harold and Maude (1971), Elliot’s freshman effort established many of his recurring ideas, from bodily humor to confusion about the world’s grimmer aspects. In his depiction of platonic friendships between misfit children and their adult counterparts, Elliot’s work goes beyond the usual storybook adventures seen in most animated movies today. Perhaps to distance himself from such fare, he doesn’t call his work animation or claymation; instead, he calls them clayographies (clay animated biographies). He continued these inclinations on Ernie Biscuit (2015), another short, this one about a Parisian taxidermist who journeys to Australia.

Without the help of computer animation, Elliot arranges a distinct and tactile world with Memoir of a Snail. Consider just the opening credits, looking over heaps of hoarded material. Old watering cans, toilets, exit signs, ketchup bottles, photos, and gingerbread women are arranged in orderly chaos by their owner, who eventually realizes she has obsessive-compulsive disorder. Since his last film, Elliot has become even more detail-oriented, articulating textures and shapes so that, at any moment, one might pause the film to appreciate the tangible creation—from Pinky’s wrinkled face to the dark circles under Grace’s eyes. Unlike today’s CG animated studio fare, where digital artists use software to realize their vision, stop-motion has an incomparable physicality produced manually by an artisan’s hands. It feels more alive and even substantive than the average computer product or hand-drawn animation. Something about shaping every movement with human hands imparts the work with intimacy and personalization.

All of these formal touches might be lost if Memoir of a Snail were not such a moving, funny, and achingly sad story, told by Grace to her favorite pet snail, Sylvia. Grace starts her life story at the beginning, explaining how her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) never met their mother; she died in childbirth. But their mother passed down her affinity for snails to Grace, while their father (Dominique Pinon)—once a stop-motion animator and street performer in France who, after a drunk driver strikes him, turns to alcohol and self-pity—nourishes their playful family dynamic. But he, too, passes, leaving Grace and Gilbert to be separated into different foster homes. Born with a cleft palate, Grace, who dreams of becoming a stop-motion animator no less, was bullied at school for her appearance. And while Gilbert, a punkish radical interested in fire, would often come to her rescue, they both must fend for themselves in their respective foster homes.

Grace moves to Canberra, Australia’s “safest city,” with two accountants who have a penchant for beige interiors, nudism, and swinging. Grace keeps herself busy by collecting snail figurines, which soon consumes her life. If that sounds like Grace has it rough, Gilbert is worse off on the other side of the country, saddled with a bizarre sect of apple-centric evangelicals who force him to follow their beliefs, eat meat (he’s a vegetarian), and work under impossible conditions. He’s constantly at odds with his cruel hosts, and when they find him kissing one of their sons, they use cruel electric shocks as a form of conversion therapy. It doesn’t work, because why would it? Much like Mary and Max, some of the story unfolds in letters between the siblings, and also like in that film, Grace forms a relationship with an older friend, Pinky. As the years pass and Grace reaches adulthood, she becomes an “unloved recluse” who finally meets someone: a neighbor whose taste for milkshakes and sausages has a duplicitous purpose.

While Elliot’s animation is wonderfully specific and belongs in the same class as Selick (director of 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and 2009’s Coraline) and the animation studio Laika (ParaNorman, 2012), his writing elevates his style with confronting emotional impact. Memoir of a Snail is heartfelt and smartly observed, such as when the weary-eyed Grace remembers being told that childhood is “like being drunk; everyone remembers what you did, except you.” Although Grace lives in relative isolation, she’s well-read and has dozens of thoughtful observations about life. Whether things are down (“I just wanted the Earth to stop so I could get off”) or she engages in self-assessment (“The worst cages are the ones we create for ourselves”), the character helps turn the story into more than an animated feature by sharing wisdom from her reading. A particularly devastating moment is when Grace realizes that, had she just saved her money and not invested so much in snails, she could have afforded a plane ticket to rescue Gilbert.

A contender for the best animated film of 2024, Memoir of a Snail finds humor and humanity in the messier, less presentable aspects of life. Its characters have unpolished personalities, filled with quirks, hangups, and compulsions that the impeccable (and refreshingly unrecognizable) voice acting accentuates with idiosyncrasies and personality. And yet, Elliot manages to wrap up his story in a tidy, perhaps overly convenient solution in the final scenes that may rob the film of some—but not all—of its edge. Even so, Elliot’s interest in dejected outsiders, his understanding of weirdos and hermits, and his tendency to judge only the intolerant demonstrate an overwhelming empathy that enriches his work. He reflects on every facet of life, no matter how unpleasant, which leads to contemplative, rather existential insights courtesy of Søren Kierkegaard: “Life can only be understood backwards, but we have to live it forwards.” It’s a simple, sophisticated approach to framing a story, and an acknowledgment that sometimes you must escape the flow of life to gain perspective.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review