Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials

By Brian Eggert |

What’s worse than a maze with towering walls and filled with slimy biomechanical spiders? An endless desert populated by zombie-things called “Cranks”, where there’s nowhere to hide except the skeletal remains of ruined buildings. That’s the familiar setting of Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials, the latest YA franchise sequel to follow in the footsteps of The Hunger Games and Divergent. Director Wes Ball’s adaptation of the second installment in James Dashner’s book trilogy answers a few questions about the cryptic predecessor, but ultimately leaves viewers, particularly those unfamiliar with the books, waiting for an explanation as to what it’s all about. At least the action-centric story moves along at a fast pace, even if the over-plotted scenario employs one cliché after another, from zombies to post-apocalypse wastelands to vast secretive conspiracies.

In 1939, Argentinean-born writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths. The short story follows a Babylonian king who demands a labyrinth “so confusing and so subtle that the most prudent men would not venture to enter it” (which might as well be the labyrinth from The Maze Runner). But when an Arab king visits the Babylonian kingdom, he’s sent inside the labyrinth in an act of ridicule. Nevertheless, the Arab king escapes and resolves to attack the Babylonian kingdom, capture its king, and gets revenge by sending him into an Arab labyrinth: the inescapable desert. Add zombies, and this is the basic plot of The Scorch Trials, which picks up the instant The Maze Runner concluded. “Gladers” Thomas (Dylan O’Brien), Teresa (Kaya Scodelario), their friend Newt (Thomas Brodie-Sangster), and others have escaped “the maze trials” established by a mysterious group dubbed World Catastrophe Killzone Department (WCKD, pronounced “wicked”). They’re quickly taken away by soldiers with helicopters to who-knows-where.

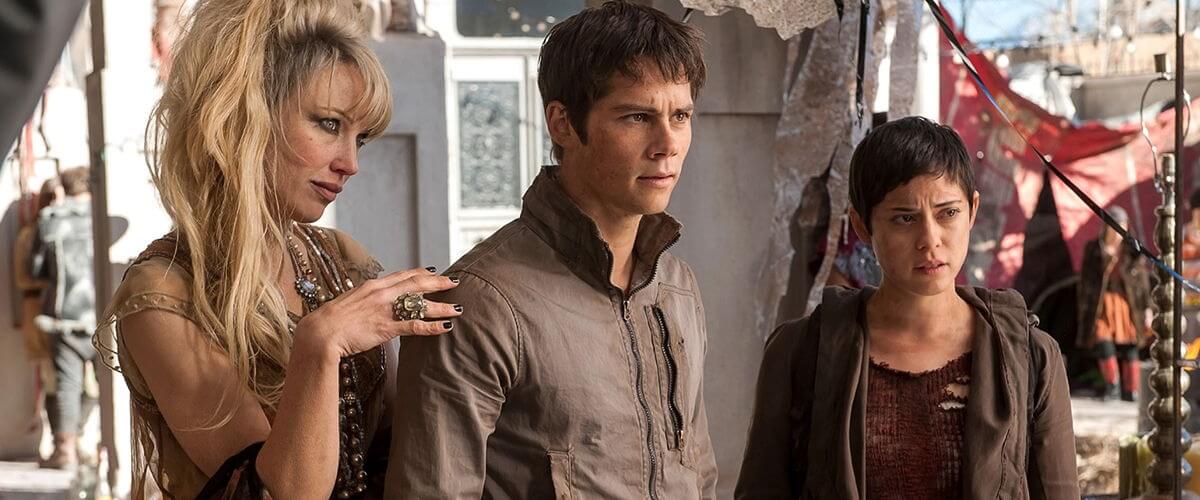

This time around, Thomas remains determined to expose WCKD, which runs human experiments to eradicate a zombie-like plague. Supposedly, their militarized rescuers, headed by Janson (Aidan Gillen), also escaped the maze trials. At first, the teen heroes have no suspicions about their hosts, who offer showers, clean clothes, and hot food. But soon they learn Janson works for WCKD too, and that they’re scheduled to be drained of their genetic immunity to the zombie virus. With this, they escape into the desert, pursued by WCKD goons and kill-crazy monsters (making the most of our culture’s fascination with zombies). Eventually, the group meets up with rebels Jorge (Giancarlo Esposito) and Brenda (Rosa Salazar), who are also determined to bring down WCKD; and they want to meet up with even tougher rebels (played by Barry Peppy and Lily Taylor), before launching an attack on The Powers That Be.

What’s frustrating is that, despite never learning the true purpose of the desert maze, The Scorch Trials does not illuminate the purpose of the labyrinth from The Maze Runner. What scientific function did it serve? What is WCKD learning through these experiments? Why did no one warn the founders of WCKD that their acronym sounded like a synonym for “evil”? Not knowing The Master Plan leaves the viewer in the dark and leaves the film feeling devoid of conflict, thus losing our attention. Unlike the ostentatious Capital in The Hunger Games or the emotion-suppressing government in Divergent, the evil empire in The Maze Runner series operates in the shadows. For all we know, the last film will pull back to reveal the three adventures are all just an elaborate videogame being played by a 12-year-old boy on his Playstation 4. Worse, the muddled plot of The Scorch Trials doesn’t have the singular purpose of its predecessor (i.e. escape the maze).

There’s a moment in The Maze Runner when the teens find a monitor, where Patricia Clarkson’s WCKD Director of Operations Ava Paige says, “I’m sure by now you all must be confused, angry, frightened.” Well, she got the first two right. The Scorch Trials carries on from one sequence to another, and we cannot help but wonder where it’s all leading. Ball’s production looks expensive, but with all the running and cinematographer Gyula Pados’ overused Shaky-Cam style, it’s difficult to care when you can barely follow the action. Indeed, the plot seems almost entirely comprised of Thomas sprinting from this or that threat: narrowly sliding under a closing door, narrowly escaping a horde of Cranks, narrowly surviving the sweltering desert, narrowly running from more zombies, and narrowly getting away from WCKD. Eventually, the viewer just wants Thomas and friends to sit down, take a break, read a book maybe. Unlike other YA franchises, the basic emotional underpinnings remain vacant in The Maze Runner movies, and the action isn’t good enough to keep our attention.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review