May December

By Brian Eggert |

Todd Haynes investigates the chronic rationalization and detachment borne from a scandal in May December, a film that, like the director’s most intricate works, contrasts how people present themselves against the reality that subsists underneath. Whether diagnosing the malady of prisons disguised as refuges in Safe (1995), exploring the pretense of 1950s social decorum in his Sirkian homage Far From Heaven (2002), or peeling away the many layers of Bob Dylan in I’m Not There (2007), Haynes is fascinated by people who compartmentalize inconvenient truths to shield themselves from having to admit that they want something they’re not supposed to want. But rather than a clinical analysis of his characters’ multifacetedness, Hayes dabbles in sensationalism, knowing that the ideas behind his film must grab his audience. So, while May December considers an artist who attempts to preserve emotional distance from the subject she wishes to portray—along with traumatized people who place their pain in a box because it’s easier and criminals who rationalize their behavior because they can’t admit the ugly truth—it’s also a delightful piece of ironic, darkly funny, and occasionally thrilling melodrama. Wrought with moral ambiguities and several outstanding performances, this ranks among Haynes’ best films.

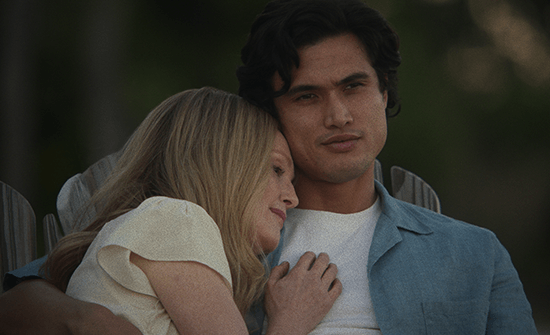

Natalie Portman stars as Elizabeth Berry, a famous actor who arrives in Savannah to shadow the subject of her next great role, Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore). Back in 1992, Gracie, then a pet store worker, was at the center of a national scandal when she was caught having an affair with her 7th-grade coworker. She was 36 at the time. After a stint in prison, where she had her first child with the boy, Gracie married him upon her release, and they had more children together. When Elizabeth arrives to research them, Gracie and her husband, Joe Yoo (Charles Melton), live an outwardly idyllic life in Savannah with their children, who will head to college after graduation in a few days. Joe is now 36 and, along with his older wife, about to be an empty nester. This has left him finally asking questions about what happened all those years ago. Despite the headlines from the time proclaiming “Forbidden Love,” and regardless of the occasional box of feces left on their doorstep by anonymous neighbors who don’t want them in the community, Gracie insists to Elizabeth that they live a happy life. Any of Elizabeth’s questions that imply the contrary or test Gracie’s carefully structured façade are met with impatience, exposing her disturbing fragility.

Inspired by the real-life story of Mary Kay Letourneau, the screenplay by Samy Burch (from a story credited to Burch and Alex Mechanik) begins with a portrait of the scandalous relationship. May December presents Gracie, and later Joe, through the seemingly objective gaze of Elizabeth, who will use her time with them to inform her eventual performance. Upon observing Gracie’s outwardly polished suburban lifestyle, she sees a person in denial who refuses to accept that her community despises her and that her idyllic family isn’t as wholesome as she pretends. Elizabeth quickly learns that reality has never penetrated Gracie and Joe’s world. They might even believe that “cultural memory” will soon catch up and reassess them, similar to how the media once trashed subjects of scandal such as Britney Spears and Monica Lewinski and later championed them for their resilience. When will people realize that their love is real? But as much as Elizabeth probes, Gracie claims she never thinks about the past. Everything is perfect, so why should she? Meanwhile, Elizabeth interviews those close to Gracie, such as her first husband, Tom (D. W. Moffett), with whom Gracie had children. Among them is Georgie (Cory Michael Smith), the erratic and attention-seeking adult son from her first marriage, who implies that Gracie, too, was raped as a child, and so she may have repeated her trauma upon Joe.

Inspired by the real-life story of Mary Kay Letourneau, the screenplay by Samy Burch (from a story credited to Burch and Alex Mechanik) begins with a portrait of the scandalous relationship. May December presents Gracie, and later Joe, through the seemingly objective gaze of Elizabeth, who will use her time with them to inform her eventual performance. Upon observing Gracie’s outwardly polished suburban lifestyle, she sees a person in denial who refuses to accept that her community despises her and that her idyllic family isn’t as wholesome as she pretends. Elizabeth quickly learns that reality has never penetrated Gracie and Joe’s world. They might even believe that “cultural memory” will soon catch up and reassess them, similar to how the media once trashed subjects of scandal such as Britney Spears and Monica Lewinski and later championed them for their resilience. When will people realize that their love is real? But as much as Elizabeth probes, Gracie claims she never thinks about the past. Everything is perfect, so why should she? Meanwhile, Elizabeth interviews those close to Gracie, such as her first husband, Tom (D. W. Moffett), with whom Gracie had children. Among them is Georgie (Cory Michael Smith), the erratic and attention-seeking adult son from her first marriage, who implies that Gracie, too, was raped as a child, and so she may have repeated her trauma upon Joe.

However severe this subject may sound, Haynes implants intentional irony and humor into the mix. The earliest indication of May December’s wryness occurs before Elizabeth arrives at Gracie’s home for an all-American cookout. Doom-laden notes on the score’s piano underscore Gracie looking into her refrigerator, and a quick zoom punctuates her horrifying observation: “I don’t think we have enough hot dogs.” Marcelo Zarvos’ ironic thriller score borrows from Michel Legrand’s music for Joseph Losey’s The Go-Between (1971), but it sounds straight out of a made-for-TV movie on the Lifetime network, which, by the looks of the film-within-the-film about Gracie that Elizabeth watches, already exists within the diegesis. Playing even the most sardonic moments straight, Haynes invites the viewer to look incisively at the characters and consider what they conceal. Cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt captures them in bright, open shots that, in another context, might seem honest and wholesome. Here, there’s an acknowledgment that everything we see has been carefully arranged to appear proper and regular, though it’s anything but.

May December is about surfaces and penetrating them in the same manner as so much of the director’s other work, and digging beneath what we see is always the most interesting part. It’s also dangerous because people bury aspects of their lives as a defense mechanism. Unearthing those uncomfortable realities can be painful and treacherous. Beyond how Gracie desperately maintains a state of normalcy despite being a registered sex offender, Haynes implants a sense of dread by establishing her penchant for hunting fowl. Our awareness that Gracie owns guns and can shoot leaves us uncertain about how Elizabeth’s research trip might end. But the surfaces aren’t only Gracie and Joe’s to penetrate; there’s also the actress’ seemingly gracious, nonjudgmental presence to consider. When fans recognize her in public, Elizabeth puts on phony gratitude. She also shields her intentions for the eventual film by repeating a practiced response that she hopes it’s “true.” But Elizabeth sees their story as a surface, a “story” rather than someone’s life, and she begins to reflect that.

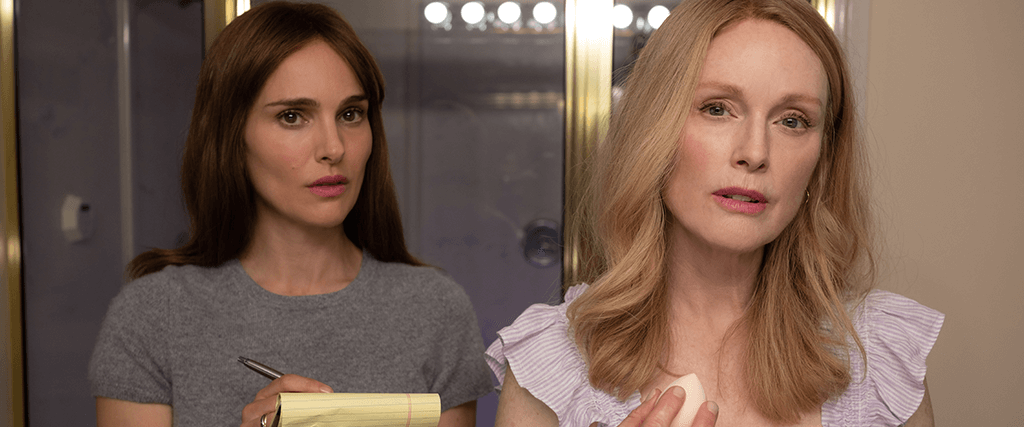

Indeed, Elizabeth’s interest in Gracie has a mirroring effect, and Haynes uses mirrors in several crucial scenes, inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966). Among the most potent is when Elizabeth watches Gracie putting on makeup, and then Gracie resolves to apply blush and lipstick on Elizabeth. The scene, shot from the mirror’s perspective, finds the two face-to-face, inches away, with Gracie using her fingers to dab a pinkish shade onto Elizabeth’s lips. The tension and magnetism between them are undeniable. Later, in perhaps May December’s most stirring scene, Elizabeth practices her performance as Gracie in the mirror, reading from a secret love letter that Gracie gave Joe when they first started communicating (which, in an achingly funny detail, he kept hidden inside a Mortal Kombat II game box for Sega Genesis). Elizabeth gets so far into her character’s head that she begins to see the appeal of crossing the line as Gracie did. In one scene, she looks at audition reels for the boys who might play Joe onscreen; none of them are “sexy” enough, she says. Elsewhere, she speaks at Gracie’s daughter’s school about acting and offers a far-too-intimate response to a student’s question about shooting sex scenes. Elizabeth confesses interest in “moral gray areas” for artistic exploration, but to what degree do these interests motivate her outside of her career?

Indeed, Elizabeth’s interest in Gracie has a mirroring effect, and Haynes uses mirrors in several crucial scenes, inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966). Among the most potent is when Elizabeth watches Gracie putting on makeup, and then Gracie resolves to apply blush and lipstick on Elizabeth. The scene, shot from the mirror’s perspective, finds the two face-to-face, inches away, with Gracie using her fingers to dab a pinkish shade onto Elizabeth’s lips. The tension and magnetism between them are undeniable. Later, in perhaps May December’s most stirring scene, Elizabeth practices her performance as Gracie in the mirror, reading from a secret love letter that Gracie gave Joe when they first started communicating (which, in an achingly funny detail, he kept hidden inside a Mortal Kombat II game box for Sega Genesis). Elizabeth gets so far into her character’s head that she begins to see the appeal of crossing the line as Gracie did. In one scene, she looks at audition reels for the boys who might play Joe onscreen; none of them are “sexy” enough, she says. Elsewhere, she speaks at Gracie’s daughter’s school about acting and offers a far-too-intimate response to a student’s question about shooting sex scenes. Elizabeth confesses interest in “moral gray areas” for artistic exploration, but to what degree do these interests motivate her outside of her career?

May December would have been compelling enough with Portman and Moore giving two tour-de-force performances, but Haynes also lends Joe considerable dimension, and Melton’s performance is terrific. Joe has been caught in arrested development since first meeting Gracie. An adult man-child stunted by Gracie’s criminal seduction, he claims to have felt “seen” by her, but Gracie bosses him around as though she’s talking to one of their children. She serves him cake with a big glass of milk like a kid, and her nagging wife routine has disturbingly maternal undertones. It’s a tragic portrait of a sheltered, inexperienced man. When his teenage son smokes a joint on the roof, Joe joins and takes his first ever puff, leading to a painful scene where the father’s fragile veneer cracks and he sobs, “I can’t tell if we’re connecting, or I’m creating a bad memory for you.” He can no longer distinguish whether his life is happy or in a perpetual state of damage. Even though Elizabeth sees Joe as a victim, she finds herself drawn to him, and she crosses a line when she demonstrates through casual sex that he can have a life without Gracie. When Joe is upset by her immediate coolness afterward, her justification that “this is just what grown-ups do” sounds like a note of warped rationalization that Gracie might employ.

Moore has collaborated with Haynes for nearly 30 years, beginning with her appearance in Safe, and has given some of her finest performances in his films. Gracie is one of her most fascinating, subtly monstrous characters. Watch her pitch-perfect delivery of devastating lines about her daughter’s “brave” defiance of “unrealistic beauty standards” by wearing a dress that reveals her arms, or her graduation gift of a scale to her other, older daughter. She could give passive-aggressive Minnesotans a run for their money. Moore, one of the great screen criers, also breaks down over Gracie’s arbitrary concerns, such as when one of her clients cancels an order for her cake-making business. But her tears about such superficial nonsense suggest they’re for something more significant that she would never admit. Portman, too, lends a complexity to her performance that proves she only gets better as the years pass. As Elizabeth seems to lose herself, we wonder whether her behavior is just an artist’s empathy for her subject taking over, something rotten inside Elizabeth, or both. Elizabeth will play Gracie, but she always performs by reserving aspects of herself. And Portman marvelously keeps us guessing through the final, unsettling scene where it’s “getting more real.”

From the first close-up shots of monarch butterflies laying eggs on milkweed plants, Haynes instills an emphatic theme of growth, nurturing, and maturation into adulthood. If this is the natural process, it has been stunted for people like Gracie and Joe, who have each experienced something that has infantilized aspects of their identities. Consider how Joe raises monarchs in captivity to ensure they can grow safely before setting them free. Perhaps he watches monarchs grow and go free because he never could. Certainly, this is reflected in how Gracie and Joe’s two youngest children will be graduating and leaving them. Now that he has raised children and set them loose on the world, he considers the experiences he never had, leading to devastating scenes. Joe’s breakdown with Gracie is among the film’s rawest moments: “What if I was too young?” he asks. But Gracie defends herself still with a textbook shift of the blame: “You seduced me.” As the outsider, and an actress whose role is to look at her character with empathy, Elizabeth can identify with and understand them; however, she doesn’t see how her sympathy and artistic distance can be dangerous, or she doesn’t care.

From the first close-up shots of monarch butterflies laying eggs on milkweed plants, Haynes instills an emphatic theme of growth, nurturing, and maturation into adulthood. If this is the natural process, it has been stunted for people like Gracie and Joe, who have each experienced something that has infantilized aspects of their identities. Consider how Joe raises monarchs in captivity to ensure they can grow safely before setting them free. Perhaps he watches monarchs grow and go free because he never could. Certainly, this is reflected in how Gracie and Joe’s two youngest children will be graduating and leaving them. Now that he has raised children and set them loose on the world, he considers the experiences he never had, leading to devastating scenes. Joe’s breakdown with Gracie is among the film’s rawest moments: “What if I was too young?” he asks. But Gracie defends herself still with a textbook shift of the blame: “You seduced me.” As the outsider, and an actress whose role is to look at her character with empathy, Elizabeth can identify with and understand them; however, she doesn’t see how her sympathy and artistic distance can be dangerous, or she doesn’t care.

Deliciously complex and nuanced, May December is the kind of film that should be watched and watched again. Burch’s thoughtful screenplay, which Portman brought to Haynes to spark their first collaboration (of hopefully many), leaves much for the viewer to consider. Is Gracie a pure predator or an insecure victim attempting to find some stability in her life? To what extent do Elizabeth’s transgressions approach those of her subject? Such ambiguities will fester in the viewer for days afterward. But then, the film also intrigues with its naturalistic performances and Zarvos’ heightened score, and the stylistic incongruity they produce. The interplay perfectly harmonizes with the film’s themes about artificial surfaces and the reality underneath, the truth and the lies people tell to protect themselves, and the persistent duality of its characters. It’s all the more fascinating when Haynes shows Gracie or Elizabeth (or both) looking into the mirror at several points in the film, thus at the camera and the spectator, for what should be an honest moment. But even when confronted head-on and looking at themselves, neither Gracie nor Elizabeth fully reveal themselves, and their performances become even more necessary. May December is an unassuming and brilliant film whose unanswered questions invite our curiosity, ceaseless contemplation, and enthusiastic admiration.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review