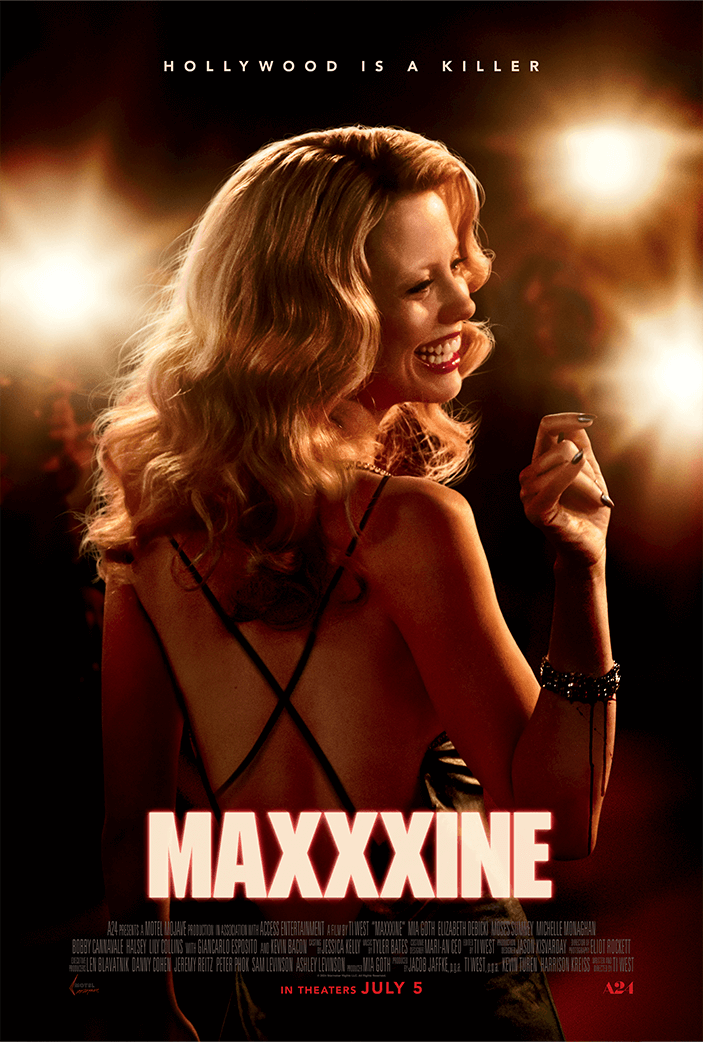

MaXXXine

By Brian Eggert |

In MaXXXine, Mia Goth returns as the aspiring star who left her Bible-thumping family in Texas to make a name for herself. She started in porn, and now, in 1985, she has a chance to appear in her first Hollywood production, a B-movie called The Puritan II that exploits the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. Central to the religious right’s fervor at the time was a paranoid theory that popular entertainment—horror movies, heavy metal music, even children’s cartoons—was corrupting the minds of America’s youth, implanting devilish messages into media, and feeding a vast occultist conspiracy. The phenomenon, in part a reaction to 1960s counter-culture, sexual liberation movement, and emergence of second-wave feminism, and fuelled by Reagan-era values, petered out by the decade’s end. However, such dogmatic absolutism has returned in recent years, with nouveau fascists wagging their fingers at people whose values don’t match their conservative worldviews or bend to their Christian ideology. But Goth’s Maxine Minx won’t let anyone stop her ascension—not the repressed in middle America, not religious groups who claim she’s been possessed by Satan, and certainly not the predators who stalk young women at night. Besides a loving throwback to 1980s sleaze, MaXXXine presents a cultural and moralist clash that feels not only germane but essential for today.

The sequel continues a theme its writer-director Ti West established in his 2022 hit, X, and explored further in its prequel, Pearl, later that year. Both charted a starry-eyed ingénue determined to become a star, though she’s confronted by someone trying to stop her progress. The titular character in Pearl, set in 1918, dreams of becoming a dancer in moving pictures, but her strict, religious mother refuses to let Pearl (also Goth) leave the farm. After losing an audition, Pearl lashes out, and anyone not supporting her vision meets a nasty end. Sixty years later, in X, an amateur adult film crew become victims of a “Texas Porn Star Massacre” when they rent out Pearl’s guest house to shoot their movie. Only Maxine survives Pearl’s repressed jealousy; whereas Pearl lived without fulfilling her desires and gaining the attention she yearned for, Maxine will not allow such a fate to befall her. West’s trilogy, while pulpy and full of gleeful genre flourishes, continues to remark on this social conflict in MaXXXine, between those who want to test their limits and express themselves and those who want to prevent everyone from exploring anything outside of their ridgid way of life. When two opposing worldviews collide in West’s trilogy, there will be blood.

Resituating the story from rural Texas to Hollywood, West presents MaXXXine as an homage to salacious Hollywood-set thrillers from the 1980s, such as Vice Squad (1982) or Body Double (1984). West establishes this era of Hollywood using the “Tech Noir” aesthetic popularized by The Terminator (1984), deploying a killer soundtrack of ‘80s hits and at least one snappy, nostalgic montage (assembled by West, serving as editor) that juxtaposes the entertainment industry with its seedy underbelly. Here’s a world rife with cookie jars full of cocaine, rampant nightly news stories about the Satanic Panic, home video fuzz, steamy alleyways, sexual temptation, and dangers in the form of the Night Stalker—a serial killer haunting Los Angeles after dark with a series of vile murders and rapes. Despite danger everywhere, Maxine endures, having made a name for herself in porn and performing in peep shows under a Louise Brooks wig, supported by her ferocious agent-lawyer (Giancarlo Esposito). More confident now that she’s successful, she hasn’t lost her edge. Take when she’s confronted by a creep with a knife dressed like Buster Keaton, who learns the hard way—in one of the film’s delightfully over-the-top displays of gore—not to corner Maxine Minx.

Resituating the story from rural Texas to Hollywood, West presents MaXXXine as an homage to salacious Hollywood-set thrillers from the 1980s, such as Vice Squad (1982) or Body Double (1984). West establishes this era of Hollywood using the “Tech Noir” aesthetic popularized by The Terminator (1984), deploying a killer soundtrack of ‘80s hits and at least one snappy, nostalgic montage (assembled by West, serving as editor) that juxtaposes the entertainment industry with its seedy underbelly. Here’s a world rife with cookie jars full of cocaine, rampant nightly news stories about the Satanic Panic, home video fuzz, steamy alleyways, sexual temptation, and dangers in the form of the Night Stalker—a serial killer haunting Los Angeles after dark with a series of vile murders and rapes. Despite danger everywhere, Maxine endures, having made a name for herself in porn and performing in peep shows under a Louise Brooks wig, supported by her ferocious agent-lawyer (Giancarlo Esposito). More confident now that she’s successful, she hasn’t lost her edge. Take when she’s confronted by a creep with a knife dressed like Buster Keaton, who learns the hard way—in one of the film’s delightfully over-the-top displays of gore—not to corner Maxine Minx.

While there’s ample sociopolitical purpose behind MaXXXine, the storytelling here feels less immersive than its predecessors, as though West has more interest in portraying Hollywood of this era than continuing Maxine’s story. With Maxine headlining in the new movie by horror director Elizabeth Bender (Elizabeth Debicki), she faces a mysterious threat at the cusp of her legitimate stardom, and not just from the protesters outside the set of The Puritan II declaring her new movie “blasphemy.” Someone is killing her friends, inviting strippers and adult film stars up to a house in the Hollywood hills, where they’re slain, branded with a pentagram, and dumped in the city. The culprit also leaves a copy of a police evidence videotape with a scene from The Farmer’s Daughters—the porn she was making with friends before they were slaughtered in X—at Maxine’s door. The two LAPD detectives (Michelle Monaghan, Bobby Cannavale) on the case question her. A sleazy private detective (Kevin Bacon) also contacts her on behalf of his mysterious employer. Who’s behind all this? Is it the Night Stalker, the real-life serial killer mounting a body count upwards of 15? Or perhaps it’s another case of hypocrites targeting the sexually liberated with violence and cruelty?

As the protagonist, Maxine can feel a little lost in this sensory overload of the setting and threats therein, leaving Goth with fewer showy moments than her previous efforts with West. The director remains preoccupied with his pastiche of Hollywood-based thrillers, though he never quite resorts to blatant references, preferring to replicate the flavor of his influences. He also has a higher budget. Whereas he made X for $1 million and Pearl for the same, the number of stars and locations in MaXXXine suggest the director had more resources. Maybe this presented a distraction, whereas the limited budget on the earlier efforts required more invention and smaller moments with his actors. By contrast, the third installment of this series relies on elaborate, electric set-pieces and sequences, such as an impressive Goodfellas-style oner early on, where cinematographer Eliot Rockett follows Maxine into a strip club, through a porn shoot, and to her dressing room. Other flourishes seem too enticing to resist, such as a chase through the Universal backlot, culminating at the Bates house from Psycho (1960). Likewise, the film’s climax unfolds around the Hollywood sign.

All of this material—much of it covered in FX’s American Horror Story: 1984—conspires to produce a film that’s more impressive for its individual moments and thematic intent than the particulars of the narrative. If this sounds like disappointment on my part, maybe that’s because my love of X and Pearl, which has only heightened upon subsequent rewatches, established unreasonable expectations. Even so, West resorts to clunky devices to underline the connections for his audience, including flashbacks to X or even to earlier scenes in the movie, shown as scratchy memories in Maxine’s mind. His star-studded cast also proves distracting, if only because many of their roles feel truncated, among them Halsey, Debicki, Monaghan, Cannavale, Lily Collins, and Sophie Thatcher. Each appearance amounts to a few brief scenes to take advantage of their recognizable faces, creating a scope in which Goth and her character feel like afterthoughts. More in the independent horror spirit is the security guard played by Larry Fessenden, whose production company, Glass Eye Pix, gave West his start in the early 2000s.

All of this material—much of it covered in FX’s American Horror Story: 1984—conspires to produce a film that’s more impressive for its individual moments and thematic intent than the particulars of the narrative. If this sounds like disappointment on my part, maybe that’s because my love of X and Pearl, which has only heightened upon subsequent rewatches, established unreasonable expectations. Even so, West resorts to clunky devices to underline the connections for his audience, including flashbacks to X or even to earlier scenes in the movie, shown as scratchy memories in Maxine’s mind. His star-studded cast also proves distracting, if only because many of their roles feel truncated, among them Halsey, Debicki, Monaghan, Cannavale, Lily Collins, and Sophie Thatcher. Each appearance amounts to a few brief scenes to take advantage of their recognizable faces, creating a scope in which Goth and her character feel like afterthoughts. More in the independent horror spirit is the security guard played by Larry Fessenden, whose production company, Glass Eye Pix, gave West his start in the early 2000s.

If David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) showed how Hollywood eats people up by turning their dreams into nightmares, MaXXXine is about the endurance it takes to become a star. West opens his film with an apt quote from Bette Davis: “In this business, until you’re known as a monster, you’re not a star.” To be sure, here’s a warts-and-all portrait of Hollywood as a place of exploitation and predatory drives, where a woman like Maxine, who knows what she wants and will do anything to get it, faces danger but can also realize her dreams. Maxine is willing to fight (and kill) for those dreams, a motivation encapsulated by the motto passed down by her preacher father: “I will not accept a life I do not deserve.” Still, West’s psychosexual thriller sometimes gets lost in the scope of 1980s Hollywood, resulting in a sequel that feels less formally daring and boundary-pushing than its predecessors. Then again, it’s a film that also confronts today, commenting on the so-called Moral Majority and characterizing them as a band of self-righteous zealots capable of vile crimes. Overall, West’s filmmaking remains gleefully indulgent, while the cast has fun with the juicy material. Although it doesn’t meet the standards of X and Pearl, it remains capable of possessing its audience with a confident presentation, a committed central performance by Goth, and a million seedy details that flesh out a story about sex, violence, fame, and repression.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review