Reader's Choice

Marry My Dead Body

By Brian Eggert |

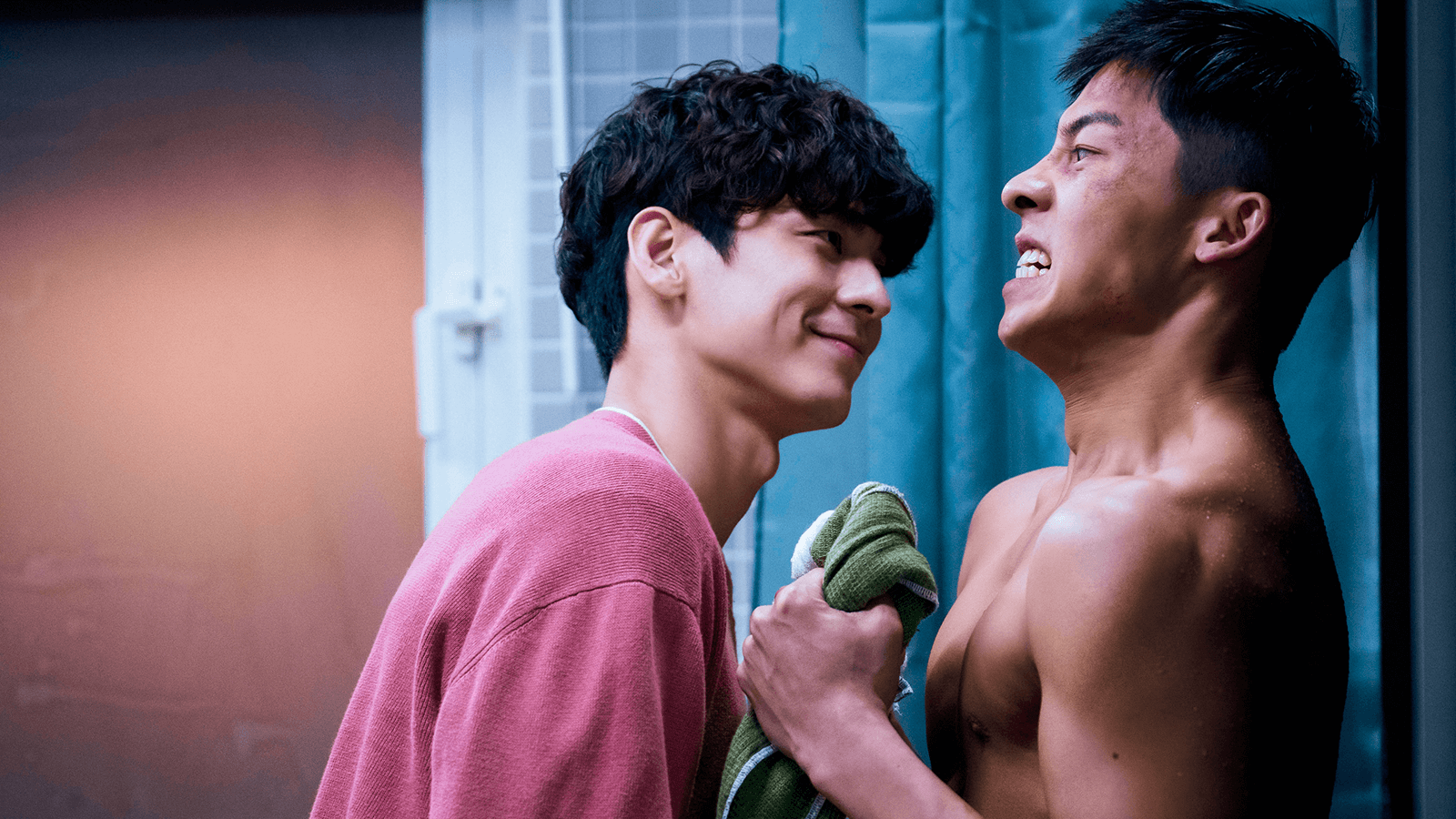

Wu Ming-han is a “dumb straight guy.” Mao “Mao Mao” Pang-Yu is a recently deceased gay man. Together, they make a perfect pair in Marry My Dead Body, a Taiwanese film that mixes and matches genres to delightful effect. Depending on where you look, the feature might be described as an LGBTQ+ comedy, an actionized police procedural, a horror movie, or even a tender story about generational divides. Sure enough, there’s a little of each in this 2023 feature, a weird and zealously entertaining romp with a tonal variety that might be perceived as an imbalance. But there’s a method to the madness of director Cheng Wei-hao’s screenplay, co-written with Sharon Wu from an original concept by Lai Chih-liang. The film has a clever way of baiting the viewer with its genre-inflected setup, filled with silly laughs, zippy car chases, supernatural apparitions, and elaborate fight sequences. But beneath its multifaceted surface is a heartfelt narrative about overcoming outmoded prejudices and accepting that identity goes beyond binary definitions, which not only impacts the characters but also comments on Taiwanese culture and politics. Although buried in Netflix’s servers after its debut at the Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival, it’s worth unearthing and celebrating as a wonderfully unclassifiable ride.

The story follows Wu (Greg Han Hsu), a vice cop whose arrest of a young, well-connected gay man earns him a demotion for his excessive and prejudicial treatment. To be sure, Wu hardly disguises his homophobia and sexism, his jocularity epitomized by the sporto high-school letter jacket he still wears into adulthood. Wu mocks his gay coworker (Chen Yen-tso), nicknaming him Chubby, and he dismisses the department’s sole woman on the force, Lin Tzu-ching (Gingle Wang), calling her a “decoration,” despite his crush on her. Their 1st Investigation Squadron has an ongoing case against a local crime lord (Tsai Chen-nan), but Wu’s behavior means he’s transferred to a lesser office with the hope of earning his way back. Elsewhere, there’s Mao Mao (Austin Lin), whose grandmother (Wang Man-Chiao) desperately wants to find a groom for her late grandson. Mao recently died in a hit-and-run, which the police could not (or would not) solve. Through a culturally specific set of circumstances, Mao’s grandmother ropes Wu into marrying the ghost of her grandson. And once they’re married, Mao appears to Wu in spectral form, inciting Wu’s homophobic slurs and general awfulness until he realizes that Mao’s ghostly abilities can help his investigation. Of course, Wu can also help Mao advance to the next life by fulfilling his dying wishes and settling his affairs on the mortal plane.

The hook draws from an ancient Chinese tradition called Mínghūn, or hell marriage, translated in English to a ghost or spirit marriage. In the original practice going back three millennia, the families of two dead people who were never married in life conduct a ceremony to ensure both of the departed achieve spiritual balance in the afterlife. An emotional salve for the mourning families, the marriage would involve a priest serving as a matchmaker, ensuring the union is a harmonious one by considering factors such as age and class. Like a traditional marriage, the bride’s family arranges a dowry, and usually, her remains are placed in the groom’s grave. In another, more recent version of this setup, the family of a deceased, unmarried woman will find a groom by setting bait in the form of a red envelope—the sort often used for monetary gifts. Placing the envelope in the street or somewhere it might be found, the family lies in wait for an unsuspecting man to pick it up. When he does, the family emerges and announces that he will be the ghost’s bridegroom. Should he refuse, he will be haunted by the ghost; however, the family often sweetens the deal with a dowry. When he agrees, a traditional wedding ceremony takes place, but the groom’s only real obligation is to keep and maintain the ghost’s ancestral tablet. And should he ever want to marry a living person, he’s free to do so.

Today, the practice is still performed in rural areas of China and Taiwan. There’s even a disturbing underground market of single folk looking for ghost brides. This demand has led to brokers who, in recent years, engage in grave robbing to acquire a woman’s corpse for a lonely groom. The bodies fetch a considerable sum, with some reports of brokers who have murdered women just to supply their clients with the makings of a ghost bride. While that sounds like a thrilling albeit less charming premise for a movie, Marry My Dead Body uses the concept as a meet-cute between its two mismatched lead characters. Mao’s grandmother has ensnared Wu with a red envelope filled with Mao’s fingernails and hair. At first, Wu resists the idea, only to realize that he will experience “a life of misfortune” until he agrees. After the odd couple marriage, Mao uses his spiritual state to taunt Wu, emerging in the shower to check out his new husband. When Wu lashes out in response, Mao, who looks composed and hardly dead aside from some occasional transparency, responds in kind—he changes himself to look like a horrifying, decomposing corpse in a spider-walk pose. The treatment continues when Mao possesses Wu and takes him out into the city naked to perform a nude pole dance for a befuddled spectator.

Marry My Dead Body has the sort of humor that, when Wu spreads his legs on the pole, it’s accented by an eagle screech sound effect. Later, Mao emerges from a wall to a slide-whistle sound. The score by Kay Liu can be equally cartoonish, but no less amusing, accenting the broad comedy moments with music worthy of a Looney Tunes short. The blend of slapstick and the macabre coupling initially recalls the dynamic in Joe Dante’s Burying the Ex (2014)—about a guy whose girlfriend comes back from the dead in zombie form—with scenes that never approach genuine frights yet use the undead visuals like a pie in the face. It also belongs in the company of Ghost (1990) and The Frighteners (1996), with the living helping the dead to resolve their unfinished business on Earth. But most of the supernatural scenes in Cheng’s film come accented by CGI barely worthy of a video game. Particularly shoddy are effects when Mao takes on the form of his post-accident body, complete with blood and a bone protruding from his neck. And when he looks otherwise normal, Mao floats around Wu. The actor must have been standing on some sort of wheeled platform to achieve the hovering effect, but that’s animated out of the picture; what remains are poor digital renderings of Mao’s legs. For the most part, though, they’re off-screen.

While the goofier supernatural sequences rely on unconvincing effects, director Cheng delivers high-intensity action, also augmented with CGI. One car chase sequence early on looks like a combination of digital animation and live action, but it’s exciting and nimbly edited by Chen Chun-hung. The action looks quite similar to Michael Bay’s Ambulance (2022), with the camera zooming past moving cars. Like that film, there’s also plenty of drone work in Marry My Dead Body to create a heightened sense of movement; though, admittedly, Bay’s similar execution proves to be the superior of the two. The cartoonishness of the humor also emerges in the action, such as an odd moment when Wu, driving at over 100 kilometers an hour, comes to a sudden, confusing halt when his vehicle is wedged between two cars blocking his path as though colliding with two large marshmallows. But after the film’s first hour, it stops relying on these flashy (and sometimes confounding) set pieces and special effects to tell its story. While the first part of this 130-minute feature concerns Wu’s attempts to restore his reputation as a cop, the second half weaves in Mao’s backstory, linking not only his death to Wu’s investigation but his queer identity to the film’s eventual melodrama.

Indeed, there’s an affecting subplot between Mao and his intolerant father (Tou Tsung-hua) sprinkled throughout Marry My Dead Body, building as the story goes. Mao dies while sending his would-be husband a teary Instagram story, but his reason for being in the street at that moment stems from a falling out with his father. Moreover, the falling out is more complex from his father’s perspective than it initially seems, resulting from a blend of stubbornness and protectiveness. The final scenes of reconciliation, with Wu speaking to Mao’s father for his ghost husband, have a heart-wrenching quality that has been thoughtfully established throughout the film. Less effective is the resolution of the central case, which involves a departmental mole (“Just like Infernal Affairs,” declares one officer) and comes equipped with at least one red herring. The reveal leads to an unexpectedly bloody finale with a high body count, but Wu’s case hardly compares next to the emotional stakes for Mao that occupy the film’s rather extended falling action.

If the story starts to drag in the finale, it’s buttressed by the genuinely moving friendship that emerges between Wu and Mao. Realizing that he’s been a prejudiced asshole, Wu warms up to his new husband and forms a platonic bond, albeit with some casual flirtation about Wu’s choice of underpants. Other endearing details emerge, such as Wu adopting Mao’s dog, named Junior Mao, a terrier who looks like an overstuffed sausage. Their honeymoon period, too, offers a few laughs. Wu sets out to fulfill Mao’s dying wishes so he can reincarnate, but Mao doesn’t feel quite strong enough about anything (aside from deleting some sexy photos and video off his phone so no one will find them). Not even catching the hit-and-run driver is enough. It’s a reconciliation with his father that Mao needs. In this subplot, Marry My Dead Body draws from and comments on a recent change in Taiwanese culture with the 2019 legalization of same-sex marriage, bringing a new awareness to LGBTQ+ themes in both politics and pop culture. More than once, the film remarks on homophobia as a backward mindset, characterizing Wu’s attitude early on as unacceptable. Mao, and before long, Wu, carry travel mugs with Pride rainbows and taglines from the campaign to legalize same-sex marriage. With this, the film can feel somewhat preachy, but with good reason to celebrate the social victory.

In the end, the film’s raison d’être might reside in conveying the adaptability of Taiwanese culture. Its balance of LGBTQ+ pride and genre-inflected absurdism is one of many such unlikely pairings in the film, including the venerable tradition of ghost marriages and new attitudes toward sexuality and gender roles. In such dichotomies, the film yearns for harmony between the old and new, traditionalism and progressiveness, and by extension, echoes Taiwan’s identity, with roots in Chinese heritage and modern Western influence. However, it can sometimes feel old-fashioned in its portrayal of queer culture, from its stereotypical gay bar to some of Mao’s behavior. Marry My Dead Body brings to mind The Birdcage (1996) in its use of stereotypes and accessible, buffoonish situations to achieve mass appeal. If its representation of LGBTQ+ culture is somewhat outmoded, it, like The Birdcage, means well and does more good than harm. Its themes feel earnestly incorporated into a film that, despite its thematic heft by the end, manages to be an escapist lark for much of the runtime. Its wacky situations and broad characters often feel ridiculous—in a fun way—and though it can feel overlong, it also takes the viewer on a worthwhile journey.

(Note: This review was originally commissioned and posted to Patreon on June 19, 2024. Thank you for your continued support, Lewis!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review