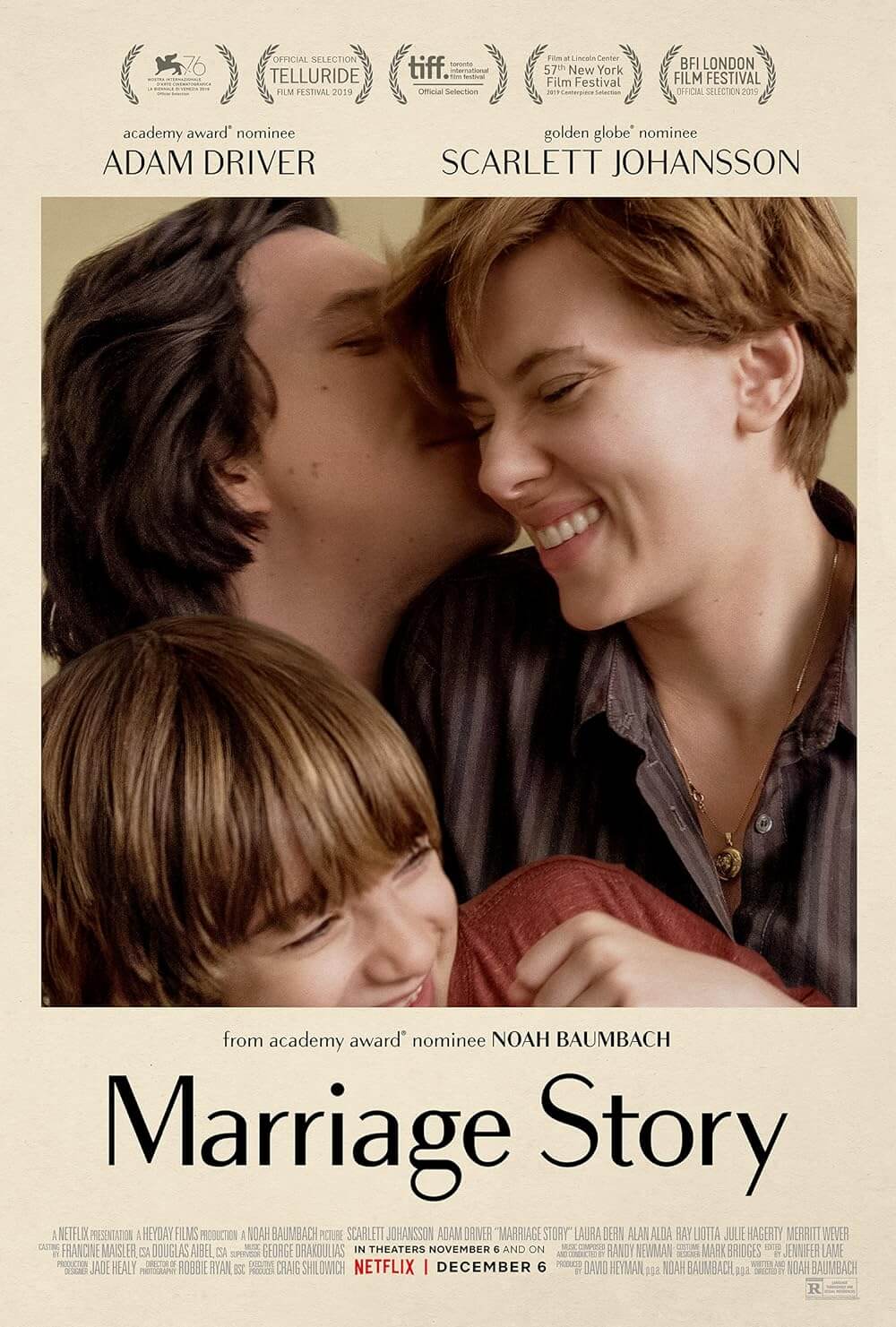

Marriage Story

By Brian Eggert |

Marriage Story opens with the voices of Charlie and Nicole, a couple played by Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson, who offer tender remarks about each other. Charlie, an acclaimed New York stage director, recites an ode to his wife, his longtime muse and lead actress in his plays. She’s a talented, generous mother, he explains in voiceover, the sort who can play as a child would with their 8-year-old son. She’s competitive at family game night, can open any jar, and charmingly leaves cups of tea around the house. When it’s her turn, Nicole tells us that Charlie looks good in whatever he wears, eats as though he’s afraid that someone’s going to steal the food from his plate, and always remembers to bring coffee for everyone in his theater company, even the intern. As they recount what they cherish about one another, we see their domestic space come to life in a few brief moments, and we understand why these two fell in love. It seems like the perfect marriage, until we realize the voiceover comes from a written exercise, assigned by a counselor to begin the process of divorce on a positive note. Those glimpses of a warm, loving household in the preceding montage belong to a couple that no longer exists; as we see them now, they can’t even sit next to one another on the subway home. The opening of writer-director Noah Baumbach’s film contains boundless emotional complexity, and the filmmaker sustains that dramatic fullness with wit and detail throughout.

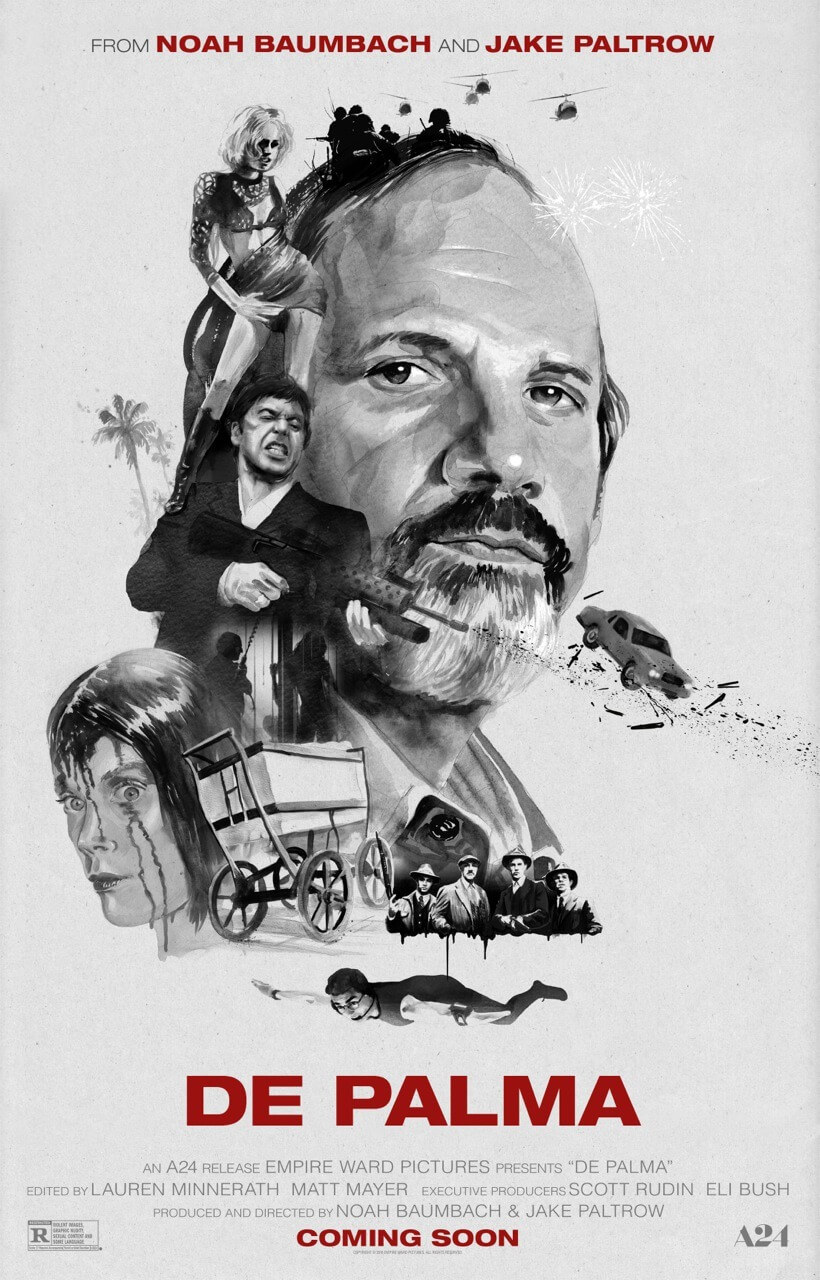

Baumbach lays out the finer points of a divorce over the film’s 136-minute runtime, from the need for and cost of legal representation to how family members, bank accounts, and living arrangements become bargaining chips on both sides. Without taking sides, Baumbach concentrates not on the technical details but on the disturbance the separation marks on his central characters. The material brings to mind Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage (1973) by way of Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives (1992), a sensitive portrait of a divorce filled with closely observed characterizations and searing confrontations. Films about the personal troubles of successful white people may seem against the grain of today’s cinema, but Baumbach’s project feels achingly personal, thus more affecting, in the way most of his films seem to have an autobiographical streak. Perhaps Marriage Story reflects his own divorce from Jennifer Jason Leigh in 2013 in some way, just as he dramatized watching his parents’ marriage disintegrate from an adolescent perspective in The Squid and the Whale (2005). Speculation aside, Baumbach shows the vulnerabilities, pettiness, anger, and regret of his characters, while also granting them genuine personalities that might seem stagier in the theatrical style of Bergman or the distinct way characters speak in the typical Allen film.

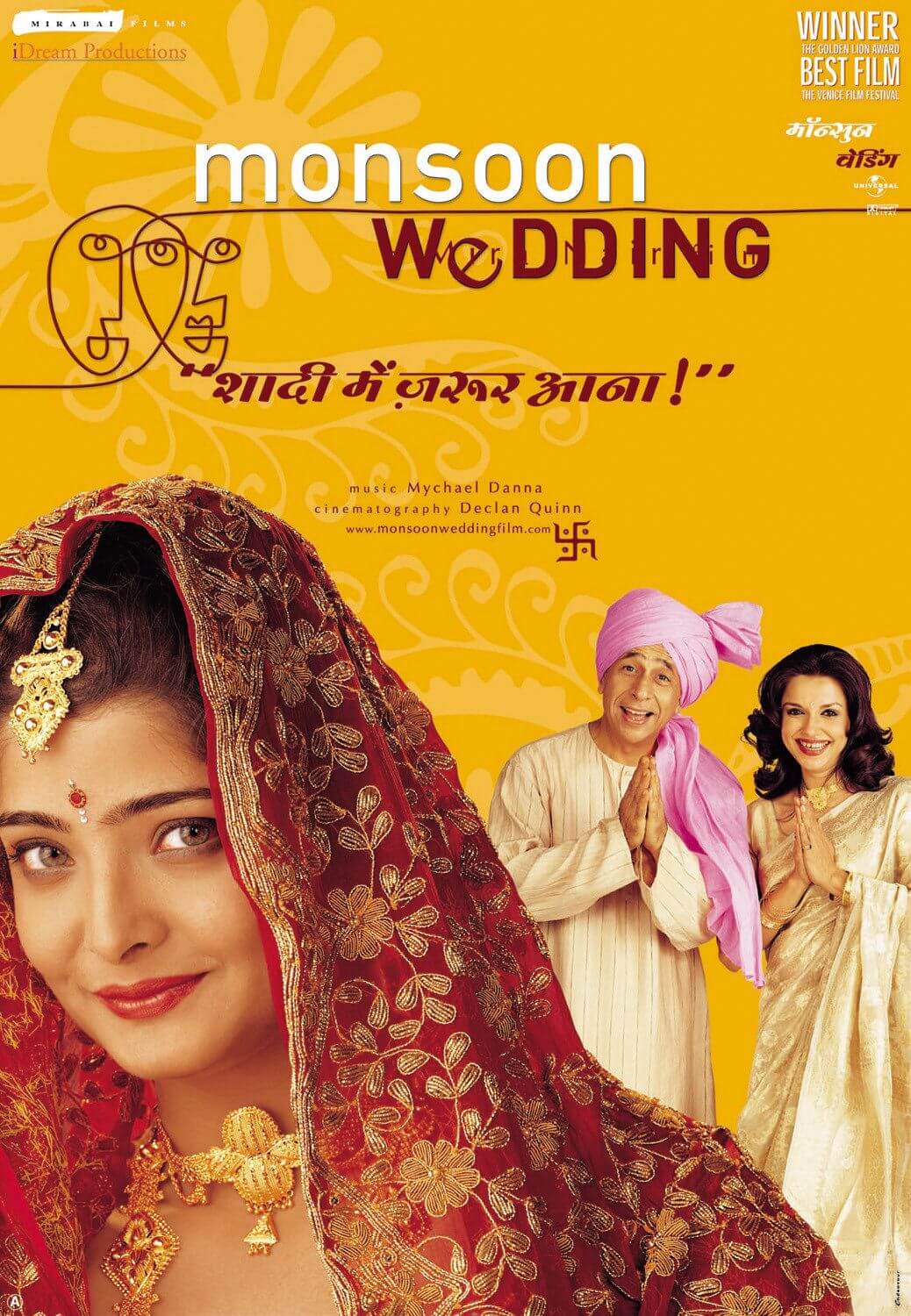

Given the subject matter, Marriage Story will doubtless be compared to Kramer vs. Kramer, the divorce drama that somehow became a massive hit in 1979 and earned an Oscar for Best Picture. But that film, starring Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep, was based on an anti-feminist book and placed the blame on the wife character, who abandoned her husband and child to self-actualize. Baumbach meets both sides of the argument on their terms, empathizing with each. Still, superficial similarities remain between the two films (even the posters look alike). The split between the New York couple occurs when Nicole, a Los Angeles native, lands a role in a television pilot and resolves to take their son, Henry (Azhy Robertson), to the West Coast, where they will live with her mother, Sandra (Julie Hagerty). Though Nicole and Charlie have resolved to keep their divorce amicable (“We’re both adults. We can do this without lawyers. We’ll just split everything evenly.”), a colleague recommends that Nicole meet with a famous Hollywood divorce attorney, Nora (Laura Dern), who begins as a shoulder to cry on before switching into a human razor. In their initial consultation, Nicole explains her reasons for initiating the separation, citing how Charlie’s artistic ambitions and tastes always supersede her own. Soon enough, Nora raises the question of infidelity, child custody, and money. What begins as a well-intentioned split between two adults becomes about having an edge in the ensuing negotiation. Marriage Story portrays divorce lawyers as sharks ready to take a bite out of the other party, and in doing so, Baumbach illustrates something broken about our culture’s unwillingness to accept that people sometimes grow out of relationships.

Given the subject matter, Marriage Story will doubtless be compared to Kramer vs. Kramer, the divorce drama that somehow became a massive hit in 1979 and earned an Oscar for Best Picture. But that film, starring Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep, was based on an anti-feminist book and placed the blame on the wife character, who abandoned her husband and child to self-actualize. Baumbach meets both sides of the argument on their terms, empathizing with each. Still, superficial similarities remain between the two films (even the posters look alike). The split between the New York couple occurs when Nicole, a Los Angeles native, lands a role in a television pilot and resolves to take their son, Henry (Azhy Robertson), to the West Coast, where they will live with her mother, Sandra (Julie Hagerty). Though Nicole and Charlie have resolved to keep their divorce amicable (“We’re both adults. We can do this without lawyers. We’ll just split everything evenly.”), a colleague recommends that Nicole meet with a famous Hollywood divorce attorney, Nora (Laura Dern), who begins as a shoulder to cry on before switching into a human razor. In their initial consultation, Nicole explains her reasons for initiating the separation, citing how Charlie’s artistic ambitions and tastes always supersede her own. Soon enough, Nora raises the question of infidelity, child custody, and money. What begins as a well-intentioned split between two adults becomes about having an edge in the ensuing negotiation. Marriage Story portrays divorce lawyers as sharks ready to take a bite out of the other party, and in doing so, Baumbach illustrates something broken about our culture’s unwillingness to accept that people sometimes grow out of relationships.

The film pits the two artists against each other in a myriad of ways, tearing away at their personal and professional exteriors until both parties have been reduced to shouting, teary piles of frustration and emotion. Baumbach alternates between the two characters, allowing the viewer to see their perspectives and increasingly separate motivations. Nicole prefers L.A., but Charlie must remain in New York to oversee the Broadway debut of his latest production. “We’re a New York family,” he insists, though every other member of his family now lives on the West Coast. Nicole has more mainstream sensibilities as a performer. Once famous for removing her top in a teen comedy, Nicole joined Charlie’s experimental theater company and helped establish it, but she’s not above returning to pop-entertainment. The dynamic recalls the one in Annie Hall (1977), in which Diane Keaton’s attraction to L.A. was a point of contention to Woody Allen’s consummate New Yorker. Of course, Henry presents another challenge as Nicole establishes herself on the opposite side of the country, making it impossible for Charlie to convince any L.A. judge that their family belongs in New York. At the same time, Nicole settles into her new home, but Charlie feels displaced by a schedule that requires him to fly across the country every weekend to a city he doesn’t know to see his child.

Charlie, a self-absorbed creative who fails to recognize his lingering selfishness, continues to wonder why they need lawyers well after Nicole has enlisted Nora. Trying to grasp the situation, he wants to take time to process and resolve the situation with Nicole. “What’s the rush,” he wonders. But Nora moves quickly, threatening full custody of Henry for Nicole unless Charlie finds representation by an appointed deadline. After an aggressive, $950-dollar-an-hour machine (Ray Liotta, in Goodfellas mode) turns him off to the prospect of playing dirty, Charlie hires a wobbly old realist named Bert Spitz (Alan Alda, as only he could play it), the sort of guy who gives his client a hug and means it. Bert tries to explain the ins and outs of his client’s limited choices, but Charlie is an artist who doesn’t understand the legality of his situation. “Are you aware of how maddening you sound?” Charlie asks. Bert replies, “I am.” The cruel and labyrinthine process of divorce remains at the center of the film. Still, Baumbach also acknowledges how its coldness has a way of laying bare the reality of Charlie and Nicole’s marriage. It’s a platform in which both parties recognize how their love and respect for one another also prevented them from communicating the more painful truth—their mutual dissatisfaction and various pain points—that if shared could have resolved their problems.

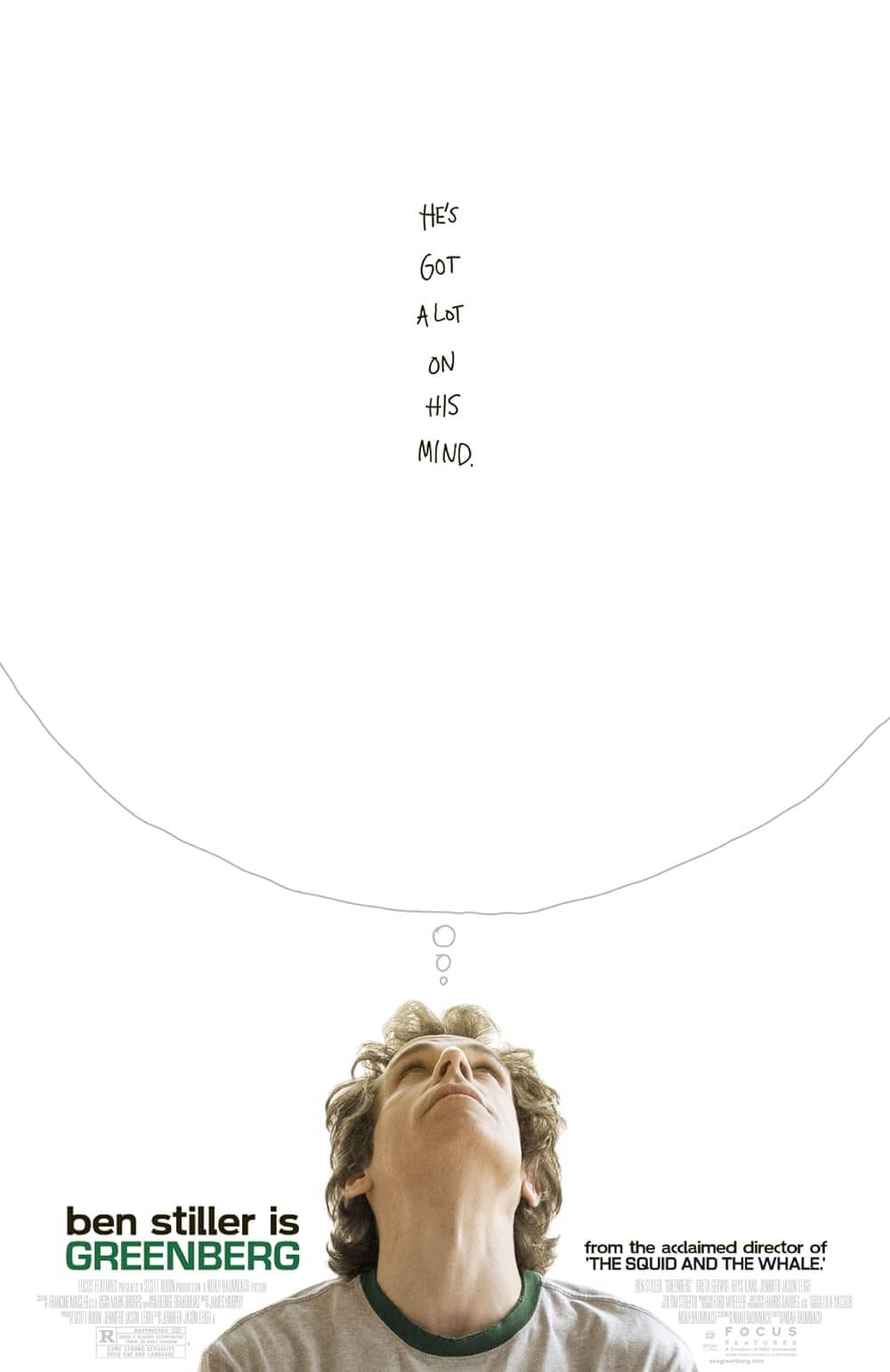

Even as Marriage Story takes the viewer through the divorce process, a painful and ugly thing, it’s a film that offers frequent laughter. Baumbach is, after all, versed in darkly comic human stories that cut to the bone. Margot at the Wedding (2007), Greenberg (2010), and Frances Ha (2012) could all be mistaken for either dramas or comedies, whereas While We’re Young (2014) and Mistress America (2015) each have a wealth of physical and screwball humor. Here, Baumbach populates the situation with charming supporting roles, such as Charlie’s cute relationship with his mother-in-law that exists independent of the impending divorce (Hagerty is delightful). Wallace Shawn also appears as an actor in Charlie’s stock company, always with a story to tell about that time that he slept with so-and-so. The highlight must be a ruthlessly comic sequence where a court-appointed observer (Mary Hollis Inboden, hilariously bereft of personality) visits Charlie’s impromptu L.A. apartment to observe his interactions with Henry. The sequence plays like an excruciating cringe-comedy scenario, beginning with Henry’s refusal to cooperate and ending when Charlie inadvertently slices into his forearm in a suicidal gesture intended as a pantomime.

Even as Marriage Story takes the viewer through the divorce process, a painful and ugly thing, it’s a film that offers frequent laughter. Baumbach is, after all, versed in darkly comic human stories that cut to the bone. Margot at the Wedding (2007), Greenberg (2010), and Frances Ha (2012) could all be mistaken for either dramas or comedies, whereas While We’re Young (2014) and Mistress America (2015) each have a wealth of physical and screwball humor. Here, Baumbach populates the situation with charming supporting roles, such as Charlie’s cute relationship with his mother-in-law that exists independent of the impending divorce (Hagerty is delightful). Wallace Shawn also appears as an actor in Charlie’s stock company, always with a story to tell about that time that he slept with so-and-so. The highlight must be a ruthlessly comic sequence where a court-appointed observer (Mary Hollis Inboden, hilariously bereft of personality) visits Charlie’s impromptu L.A. apartment to observe his interactions with Henry. The sequence plays like an excruciating cringe-comedy scenario, beginning with Henry’s refusal to cooperate and ending when Charlie inadvertently slices into his forearm in a suicidal gesture intended as a pantomime.

Still, the primary mode of Marriage Story is an emotional open wound with occasional moments of joy and humor. Nicole’s sudden coldness after initiating their separation might tilt the viewer to Charlie, until his unfaithfulness becomes apparent. Even so, Baumbach views both of them in shades of gray, imperfect and equally worthy of our compassion. Both Nicole and Charlie are subject to bad behavior early in the film, but it becomes worse when they tell their lawyers about it later as ammunition in court. Is Nicole drinking too much? Did Charlie’s infidelity cause the fissure between them? None of the specifics matter in the grand scheme of their divorce, which acts like a glacier moving through the landscape of their relationship. It’s the smaller moments that hurt the most. When Henry admits to his father that he prefers living in L.A. because “my family’s here,” his addition of “besides you” is a monumental pang. Children of divorce will identify with Henry, who seems to be in his own world, despite his parents communicating through him. What’s left is a chasm between the former couple, accentuated by the dirty practices of their legal representation. And even after the parties reach a compromise for an agreed-upon 50/50 split, Nora pushes for a little extra because she doesn’t want to feel like a loser.

Baumbach’s treatment of character and situation remains carefully observed and thoughtfully considered, and it’s so immersive that his formal technique almost disappears. Gauging his approach by the energy of the moment, cinematographer Robbie Ryan knows when to observe from a distance and when to shove the camera in an actor’s face, heightening the scenes when the couple eviscerates each other in arguments. Though much of Marriage Story makes the viewer feel implanted between Charlie and Nicole, Baumbach also lends the material a few moments of heartbreaking symbolism. In one later scene, Nicole’s power goes out, and she asks Charlie to come over and help close the front gate. With one of them on either side, they push the gate shut in a moment an aching symbolism, deftly edited by Jennifer Lame. Baumbach also inserts several formal flourishes, fades and overlays that suggest how his protagonists have a lasting connection, which is severed by their divorce. Despite such artistic touches, the director’s sometimes cerebral mode of deconstructing family relationships gives way to those pronounced scenes in his work when his characters break down or lose themselves in a moment of happiness. It’s as though Baumbach, in telling this story, complements how both Charlie and Nicole would have made it.

Two of today’s most famous movie stars have set aside their franchise costumes—Johansson as MCU hero Black Widow and Driver as moody Star Wars villain Kylo Ren—and given themselves over to the emotional heights of melodrama. Both actors give what might be career-best performances, and each has their talents displayed in their very own extended take, a frequent device in Marriage Story: Johannson is brilliant as she walks Nora through a shorthand version of their marriage and her growing resentment over her needs continually being supplanted by Charlie’s artistic ambitions. It’s a scene among many in the film that reminds us how rarely Johannson is recognized for her talents. Later, Driver gives an impromptu performance of “Being Alive” from Stephen Sondheim’s Company, a moment that gradually builds with vulnerable expression, crescendoing until it leaves the viewer ruined. Together, Johannson and Driver share a scene involving such a vitriolic argument—shot in an unpainted and unfurnished room to accentuate the unselfconscious performances, and how both parties must finally own up to their basest, most ruptured feelings—that it left me physically shaken. Enough cannot be said of these performances, unquestionably two of the best, period.

Two of today’s most famous movie stars have set aside their franchise costumes—Johansson as MCU hero Black Widow and Driver as moody Star Wars villain Kylo Ren—and given themselves over to the emotional heights of melodrama. Both actors give what might be career-best performances, and each has their talents displayed in their very own extended take, a frequent device in Marriage Story: Johannson is brilliant as she walks Nora through a shorthand version of their marriage and her growing resentment over her needs continually being supplanted by Charlie’s artistic ambitions. It’s a scene among many in the film that reminds us how rarely Johannson is recognized for her talents. Later, Driver gives an impromptu performance of “Being Alive” from Stephen Sondheim’s Company, a moment that gradually builds with vulnerable expression, crescendoing until it leaves the viewer ruined. Together, Johannson and Driver share a scene involving such a vitriolic argument—shot in an unpainted and unfurnished room to accentuate the unselfconscious performances, and how both parties must finally own up to their basest, most ruptured feelings—that it left me physically shaken. Enough cannot be said of these performances, unquestionably two of the best, period.

Marriage Story has much more on its mind than other films about divorce, which elevates it beyond the limits of its well-treaded subject matter and into a realm of extraordinary filmmaking. It’s less a confessional than an inspection of an open wound, and a mourning of the once unmarred flesh that came before. Baumbach resists pinpointing what went wrong between Charlie and Nicole to make their differences so irreconcilable; it’s too complicated to reduce the failure of their marriage to just Nicole’s need to become her own woman or Charlie’s brief affair. Baumbach’s sympathies lie with the marriage itself, even if the final scene portrays Charlie as a ghost in his former family and Nicole content in her new life. Regardless, Nicole and Charlie’s love for one another, even after the cruelest outbursts, remains palpable. The tragedy is that they realize that the proceedings have taken them to places they wished they had never gone and perhaps could have avoided. It’s a film with such a range of emotion that it is, frankly, exhausting just how much we feel. Marriage Story makes you experience the full weight of marriage. Yet Baumbach never resorts to sentimentalism; he sees the situation from a place of hard-earned perspective, and he offers raw feelings handled by an artist in complete control of his skill as a filmmaker and storyteller.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review