Maria

By Brian Eggert |

Note: Netflix will release Maria into theaters on November 27, 2024. It will debut on the streaming platform on December 11, 2024.

In the now-common introduction, where the director thanks moviegoers for seeing their film in a theater instead of streaming it, Pablo Larraín prefaces his Netflix production Maria with a brief discussion about his connection to opera. He states that his film, about the preeminent diva Maria Callas, attempts to return opera to the masses. However, it’s been a long time since opera could be afforded or was generally appreciated outside of so-called elites. You have to travel back to the nineteenth century, when Georges Bizet and Giuseppe Verdi sought to fold working-class themes into their grand stage productions, to experience when the art form had temporarily shed its privileged associations. Today, it’s easier to watch opera on public television, listen to an audio recording, or buy a ticket to a Fathom Event of the Metropolitan Opera than actually attend a live performance. So, while watching Maria with the Chilean director’s remarks in mind, I asked myself whether Larraín had made a film that would achieve his stated purpose and return opera to the masses. I don’t think he did.

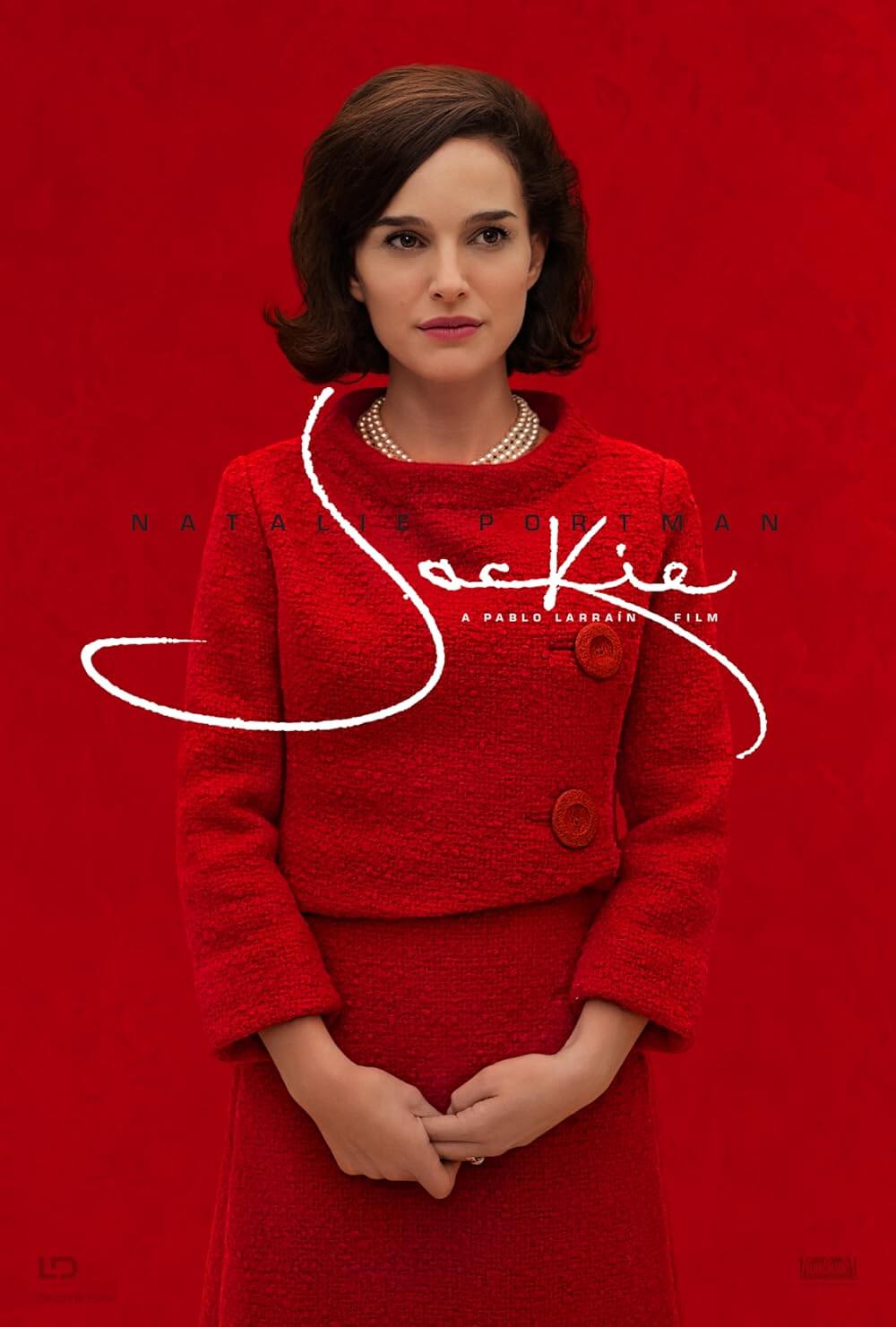

If anyone could achieve this ambition, I would’ve guessed Larraín could. And yet, his film, another in his string of impeccably crafted and unconventional portraits of iconic twentieth-century women, falls flat. For much of his early career, Larraín made incendiary films about Chile and how it changed under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. He veered into unexpected territory with Jackie (2016), his pristine drama about Jaqueline Kennedy (Natalie Portman) in the wake of her husband’s assassination. Then he made Spencer (2021), a haunting and deeply affecting portrait of Kristen Stewart’s Princess Diana living under the thumb of the British royal family. In both, he brought emotionally intense and larger-than-life figures down to earth, humanizing them and meeting them on open-hearted, expressive terms. Teaming again with Spencer screenwriter Steven Knight, Larraín might’ve ended his trilogy of pivotal women on a high note. Instead, his subject and the performer he chose to play her create challenges that not even Larraín and his skilled talent behind the camera could overcome.

Knight, a screenwriter I usually admire, particularly his use of literary symbolism, dwells on the last week of Callas’ life in 1977. Maintaining a small pharmacy of Mandrax (aka Quaaludes), steroids, and who knows what else, Maria conceals the drugs from her loyal attendants—the beleaguered valet Ferruccio (Pierfrancesco Favino), who must move Maria’s piano daily to suit her whims, and Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher), her cook. They have an affectionate bond and mutual respect with Maria, who maintains a demanding yet regal persona despite her failing health. While Larraín and editor Sofía Subercaseaux create an impressionistic narrative structure of hallucinations and flashbacks to Maria’s affair with Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer), the filmmakers struggle to penetrate her poised exterior. The story explores how Maria has had to erect walls to protect herself from her exploitative mother, who sold Maria’s voice and body to Nazi soldiers during the war, and from Aristotle, who sought to stifle Maria’s voice because of his disdain for opera. Only late in the proceedings, after Maria works to reclaim her voice after years of dormancy, do her defenses start to break down and reveal her raw humanity.

It’s a fine dramatic agenda, but Maria suffers from two misguided choices. The first is casting Angelina Jolie in the title role. Jolie plays Maria Callas, a marquee name in opera, the quintessential prima donna, with the energy of a funeral procession. It’s not that Jolie doesn’t look the part (she doesn’t); it’s that her performance doesn’t capture her character’s humanity. Jolie plays Maria with airs and reserve, evoking a mannered and self-important artiste. Certainly, Maria could be seen as a sophisticated songbird, whose years of pouring herself into her art have drained her of life. But then again, watch Maria by Callas, director Tom Volf’s 2017 documentary about the soprano that captures how she was easy to smile and had a playful facet to her personality. Other characters in Larraín’s film note her two sides, the serious artist side, known as La Callas, and the real person known as Maria. The title suggests we’ll get to know the real Maria, but Larraín and Knight focus on her from a distance—even while exploring her drug-induced hallucinations, such as dreaming up an interviewer (Kodi Smit-McPhee) or having whole conversations with phantoms.

Moreover, Jolie never disappears into the role. This is less a problem than one might suspect, since Natalie Portman didn’t quite resemble Jackie Kennedy, nor did Kristen Stewart capture the physicality of Princess Diana. But unlike these other performances in Larraín films, one can see Jolie acting. The Greek-American accent feels forced. The mannerisms feel stagey and artificial. This brings me to the second misguided choice that, admittedly, probably could not be avoided: Larraín stages several powerful scenes around Jolie lip-synching to pre-recorded performances by Callas. And while Jolie’s lips do indeed sync with the audio, my suspension of disbelief could not make the sight and sound align, likely because I couldn’t see past Jolie’s presence as an actress. The approach neutralized whole sequences predicated on Maria’s singing. I admit that this is a personal failing on my part, and perhaps those who generally appreciate Jolie’s acting more than I do would see beyond this incongruity. But the singing effect never worked for me, and given that it’s so essential to articulating dramatic moments, Maria felt hollow.

Shot by cinematographer Edward Lachman—who captured Larraín’s last film, the Pinochet-as-a-vampire tale El Conde (2023), in glorious black-and-white imagery—Maria looks aligned with Jackie and Spencer. Once again, the camera transfixes, often moving with the immersively slow cadence of a brooding, daresay operatic tragedy. Lachman shoots on an array of film stocks, each with a different purpose. The grainy 16mm for most real scenes captures the messiness of life; the 35mm monochrome images for flashbacks show how the past looks through the lens of the mind; and the 8mm home video style alternates between the appearance of archival footage, home movies, and perhaps something more expressive—as though Maria’s mind had unspooled. Larraín also injects several clapboard sequences to denote the shifts between dramatic acts, a Brechtian flourish that suggests Maria is seeing her life as cinema. This range of formal techniques captures Maria’s mental state, fractured and fuzzy, but in self-assessment mode.

In one scene, Maria says to Aristotle, “I’m sorry… am I supposed to be feeling something?” I had a similar reaction to Maria. On paper, even in terms of formal execution, the film is a hypnotic work of art, often beautiful and easy to admire. But it’s not particularly moving. Larraín finds inventive visuals to bring out Knight’s themes, and he assembles them with the craft of a true artist. Yet, they never invested me in Maria as Volf’s documentary did. The performances, Favino and Rohrwacher above all, manage some tenderness. But Jolie neither transformed herself nor allowed me to forget about her presence and lose myself in the material. The performance isn’t bad; it just doesn’t have the same overwhelming effect as Portman or Stewart did in Larraín’s earlier films. And going back to Larraín’s stated purpose from the introduction, Maria doesn’t build a bridge between opera and the masses. The film is operatic and about an operatic figure who performed in stage productions and released records of her operatic singing. But instead of making me want to visit the opera or imparting the aesthetic appeal of opera, it made me want to watch a better film about Maria Callas.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review