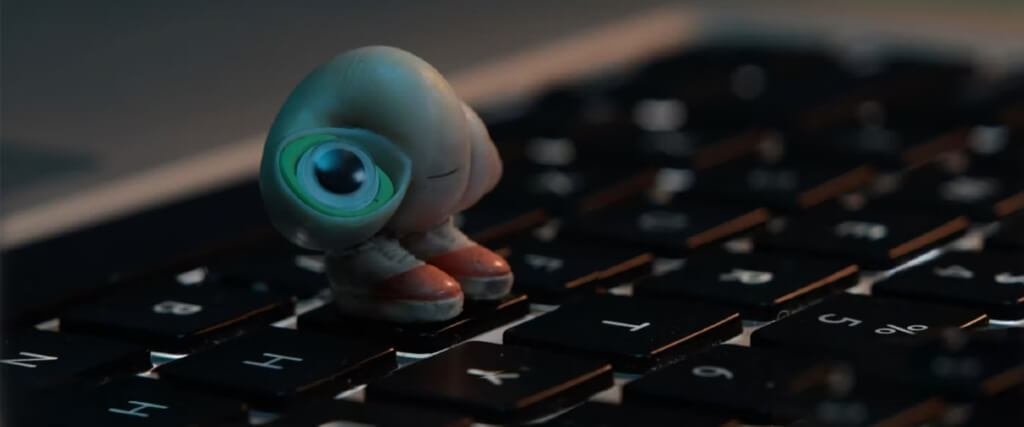

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On

By Brian Eggert |

If there’s an American equivalent to Japan’s kawaii culture of cuteness, it might be the titular character from Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, a feature-length expansion of the short films created by Dean Fleischer Camp and Jenny Slate. The kawaii aesthetic involves small, innocent, and compact cartoon animals who radiate childlike wonder and charm. But where kawaii squeezes cuteness out of infantile and bashful behavior, Marcel reaches beyond his adorable stop-motion animated exterior and offers a perspective. He’s a bit naïve to be sure. But he’s curious about the world and has an innocent yet unafraid wisdom. For example, one scene in the film involves Marcel realizing what lies beyond his home, a house in a Los Angeles suburb. Marcel, whose family is missing, learns that the world is vastly more significant than he ever knew. It’s not just the neighborhood around the house or the city, but an expansive network of cities the world over; thus, his search for his family will be much more difficult. “I had no idea,” he says in his tiny, crackly boy voice (supplied by Slate). However, Marcel isn’t someone who allows the impossible size of obstacles to get the better of him, which makes him more than just a source of mere cuteness.

First posted to YouTube in 2010, the initial short introduced the world to Marcel, a talking seashell sporting tennis shoes and one googly eye. Captured in a mockumentary style that observes Marcel in his habitat, the short consisted of a few observations about his adorable smallness. When two shorts in 2011 and 2014 followed—you can watch all three in less than 12 minutes—Marcel’s subtle philosophy of seeing a bigger picture despite his diminutive size solidified with a hint of melancholy. Now with corresponding storybooks and a feature film, it’s tempting to accuse the creators of milking the viral phenomenon for everything it’s worth. But the film doesn’t feel like a cheap commercial project with corresponding product tie-ins (though, you can find a few plushes that look like the character melted into a weird blob). Rather, the filmmakers have used their runtime to deepen the character and establish his pure and optimistic perspective. It’s more than jokes about Marcel’s stature (“Guess what my skis are… toenails from a man.”); it’s about a worldview.

Of course, the cuteness factor is high. Marcel gets around inside a tennis ball, pulls lint by a hair in place of a dog, and walks on the walls by dipping his shoes in honey. His perspective is sunny: “I like myself,” he admits without pretension. But the story becomes one of optimism in the wake of loss. Camp plays Dean, a mostly off-screen filmmaker who checks into an Airbnb to discover Marcel, who recounts that he used to live in a community of 20 or more—some shells, a few peanuts, some cereal, and other objects, all with eyes and an animated mouth. But Larissa and Mark (Rosa Salazar, Thomas Mann), the human couple who owned the place, split up, and in the fracas, most of Marcel’s family went with Mark to who-knows-where. Now Marcel lives with his aged Nana Connie (Isabella Rossellini), and they try to keep out of sight whenever a new lodger stays. Given Dean’s prolonged residence, Marcel and Nana bond with Dean and become subjects in his filming.

The screenplay by Camp, Slate, and Nick Paley incorporates some favorite lines from the shorts into the film, using what we’ve already seen as a meta conceit. Since every documentary is about its own making, Dean’s footage, the original shorts, becomes part of the story. After recording, he uploads his conversations with Marcel onto the internet, and suddenly Marcel becomes a sensation. But Marcel quickly realizes that internet fame doesn’t mean he has millions of supportive friends that will help him locate his family; instead, he observes they’re “an audience, not a community.” It’s refreshing to note that the filmmakers haven’t pandered to YouTube viewers who made Marcel go viral. True to the character, he recognizes that their participation in his story is passive. That is, except for the fine people at 60 Minutes, including Lesley Stahl. Marcel and Nana are fans: “We just call it ‘The Show,’ we love it that much.” But when the producers seek Marcel out and help him in his reunion quest, his attention is drawn to a more immediate need with Nana’s declining health. The beauty and ache of Rossellini’s voice performance cannot be overstated.

The screenplay by Camp, Slate, and Nick Paley incorporates some favorite lines from the shorts into the film, using what we’ve already seen as a meta conceit. Since every documentary is about its own making, Dean’s footage, the original shorts, becomes part of the story. After recording, he uploads his conversations with Marcel onto the internet, and suddenly Marcel becomes a sensation. But Marcel quickly realizes that internet fame doesn’t mean he has millions of supportive friends that will help him locate his family; instead, he observes they’re “an audience, not a community.” It’s refreshing to note that the filmmakers haven’t pandered to YouTube viewers who made Marcel go viral. True to the character, he recognizes that their participation in his story is passive. That is, except for the fine people at 60 Minutes, including Lesley Stahl. Marcel and Nana are fans: “We just call it ‘The Show,’ we love it that much.” But when the producers seek Marcel out and help him in his reunion quest, his attention is drawn to a more immediate need with Nana’s declining health. The beauty and ache of Rossellini’s voice performance cannot be overstated.

Meanwhile, keeping things borderline surreal and effortlessly charming, nobody ever asks how Marcel talks, nor do they inquire about his roots or that of his society of tiny creatures. It recalls how humans quickly accept Paddington bear or any number of animated characters in a real-world setting. But unlike those other saccharine examples, Marcel contains a touch of inner complexity. Just as he enjoys the social media attention before realizing it’s hollow, he longs for solitude after inevitably reuniting with his family. Some part of him enjoys being alone. Exploring this, Camp and cinematographer Bianca Cline shoot the world to emphasize Marcel’s size and isolation. He’s either dwarfed within a wide shot that accents his itsy-bitsy presence in a regular home, or the frame becomes a miniature composition invaded by a towering creature, such as Dean’s dog Arthur. In both cases, the filmmakers use Marcel’s size for no end of visual gags, plus a wealth of poignancy from the contrast between Marcel’s micro size and his massive heart. “Guess why I smile a lot,” Marcel asks Dean. “’Cause it’s worth it.”

Although Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is very cute and filled with moments that prove sentimental, the film never becomes cloyingly sweet or unabashed feel-good fare. There’s even a tinge of sadness beneath the surface, given that Slate and Camp divorced in 2016. Perhaps they inserted themselves into the proceedings with the characters played by Salazar and Mann. The film’s themes about the importance of home and family may be typical for PG-rated pictures, but its unexpectedly powerful scenes about taking care of the elderly, remembering the dead, and cherishing alone time make it unique. Given this, Marcel becomes an unlikely character for all ages. A few jokes, including a hilarious bit about “hardy hairs,” will hit adults alone and safely pass over the heads of younger people. The same goes for his riotous rant about people who sign their messages “Peace” at the end. But Marcel is a character whose subtle humor, general friendliness, and multi-dimensional personality make him feel like more than just a cute gimmick. He’s a heartwarming and resonant character, and this is a delightful little film.

(Note: As of this writing, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is currently in limited release. It will be released in Minneapolis theaters on Friday, July 15.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review