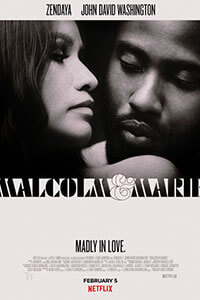

Malcolm & Marie

By Brian Eggert |

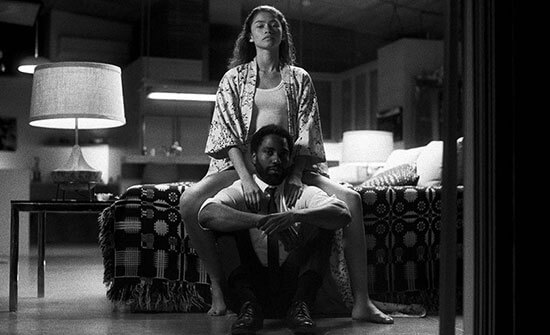

Round and round they go, where they’ll stop, well, they probably won’t. Malcolm & Marie is a chamber drama written and directed by Sam Levinson, starring Zendaya and John David Washington as a volatile couple that probably shouldn’t be together. Throughout the film, the two characters, a director and his muse, argue about past mistakes, point out each other’s flaws, come close to making-up, but soon devolve into another argument. They shout about each other’s personal transgressions, the vacuousness of the film industry, and the facile attempts of film critics to understand the true meaning of art. The dramatics seem like they might have originated with a play—and let’s face it, someone will probably create a stage adaptation—but Levinson wrote, shot, and edited Malcolm & Marie for Netflix during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Beautifully composed and acted, the film, about the give-and-take of romantic relationships and artistic inspiration, is a worthy showcase for the talent of its two leads.

The film opens with Malcolm and Marie returning home from the successful premiere of Malcolm’s new directorial effort, a story about a young woman’s struggle with addiction. It’s a wild success among critics and the audience in attendance, who declare him the next Spike Lee or Barry Jenkins. At once overjoyed and peeved about how he’ll inevitably be perceived as a Black political filmmaker—because that’s how all Black filmmakers are perceived, he believes—Malcolm alternates between pride and frustration. Marie has a similar problem, being that she’s Malcolm’s inspiration for the film. She’s happy the evening was a success, but she resents that Malcolm failed to thank her in a speech or, for that matter, cast her in the lead role or offer her screen credit. She’s a depressive who struggles with addiction, and her moods conflict with Malcolm’s selfishness and ego. When these two personality types are combined at the wee hours of the morning, plus alcohol (and Kraft macaroni and cheese), things get heated.

Levinson seems to be going for something emotionally naked like the work of John Cassavetes. Zendaya and Washington certainly deserve the comparison to Gena Rowlands and Cassavetes in, say, Opening Night (1997), for delivering two incredible performances that show a wide range of emotion. However, Malcolm & Marie doesn’t have the same improvisational intensity that Cassavetes was known for. Rather, every line feels written, and it’s only through the strength of the performances that the material doesn’t feel stagey. Self-consciously shot on 35mm by Marcell Rév, the film looks gorgeous, in no small part due to the attractive stars. The crisp monochrome style, captured in long, immersive takes, calls attention to shadows and thoughtful blocking. Consider a musical interlude sequence in the last third that transitions to a jazz saxophone on the soundtrack. The frame captures the couple in mirrors, separated by various frames and angles, yet inextricable from one another despite their visual separation. It’s a potent image, but no less obvious than a broken mirror to reflect a cracked psyche.

As a critic, it’s tempting to have a knee-jerk reaction to Levinson’s screenplay as well. His characters spend more than one scene condemning film critics and how we sometimes interpret films differently than what the filmmakers intended. Malcolm cites the tendency among white liberal critics to project political messages onto Black stories, condemns us for judging a movie based on what it might’ve been versus what it is, censures us for making biographical links, and questions the critical desire for authenticity over artistic interpretation. It’s as though Levinson designed these arguments to shield himself from any attempt by critics to dismantle his film by beating us to the punch. Admittedly, his remarks left me somewhat overly self-aware when approaching this review.

As a critic, it’s tempting to have a knee-jerk reaction to Levinson’s screenplay as well. His characters spend more than one scene condemning film critics and how we sometimes interpret films differently than what the filmmakers intended. Malcolm cites the tendency among white liberal critics to project political messages onto Black stories, condemns us for judging a movie based on what it might’ve been versus what it is, censures us for making biographical links, and questions the critical desire for authenticity over artistic interpretation. It’s as though Levinson designed these arguments to shield himself from any attempt by critics to dismantle his film by beating us to the punch. Admittedly, his remarks left me somewhat overly self-aware when approaching this review.

But what Levinson doesn’t seem willing to accept is that film critics interpret films just as filmmakers interpret reality through an artistic lens. Criticism isn’t an objective exercise, no matter what some critics might think of their own assessments. We see a film through our perspective and attempt to draw upon a particular reading, a passage that moved us, or details that stand out as artistically significant, to help readers form their own opinions. Malcolm’s rather personal remarks against the Los Angeles Times—whose guest critic Katie Walsh lambasted Levinson’s Assassination Nation in 2018—feel like the complaints of a petulant screenwriter angry that someone would dare have an opinion about his work that doesn’t align with his intent. And even though I find Levinson’s remarks tiresome, I know that I probably would feel the same way about someone who reacted so negatively to one of my reviews. The difference, I suppose, is that I wouldn’t write an entire piece about how my readers fail to understand the depths of my writing. Of course, that’s just my interpretation of this aspect of Malcolm & Marie, and it could be a projection and it could be wrong, but we’re all entitled to our opinions about art.

By the end, the couple reaches a kind of reconciliation, but one suspects that, at any minute after the end credits begin to roll, someone’s mood will turn and the verbal daggers will begin to fly. There’s a certain circular, Twilight Zone pattern to the film that suggests the evening’s routine might carry on like this until the end of time. Fortunately, Washington, who was only better in BlackKklansman (2018), and Zendaya, who graduates from the MCU and Levinson’s HBO series Euphoria into a bonafide movie star with this role, make every exchange feel true—even when the screenplay is at its preachiest. Together, they supply more than enough raw emotions and sheer acting bravado to keep our attention for a nearly two-hour two-hander.

Even so, Levinson, son of the well-regarded Barry (director of Rain Man and Wag the Dog), seems to be confronting his personal hang-ups in the guise of drama therapy. That’s how the most personal filmmakers use drama, after all. But what works best about Malcolm & Marie isn’t his commentary on the film industry or criticism in the various monologues and tirades; it’s the intimate ways in which those forces have shaped the central relationship. Sometimes Levinson’s remarks divert too much from the shifting dynamics between Malcolm and Marie, making some scenes feel laborious and soap-boxy. Other times, when the characters reveal another personal betrayal or wrinkle in their complicated past, the film manages to feel genuine. Although the viewer never quite sides with either party and never really forgets about the craft on display, watching these stars interact for nearly two hours could hardly be called a waste of time.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review