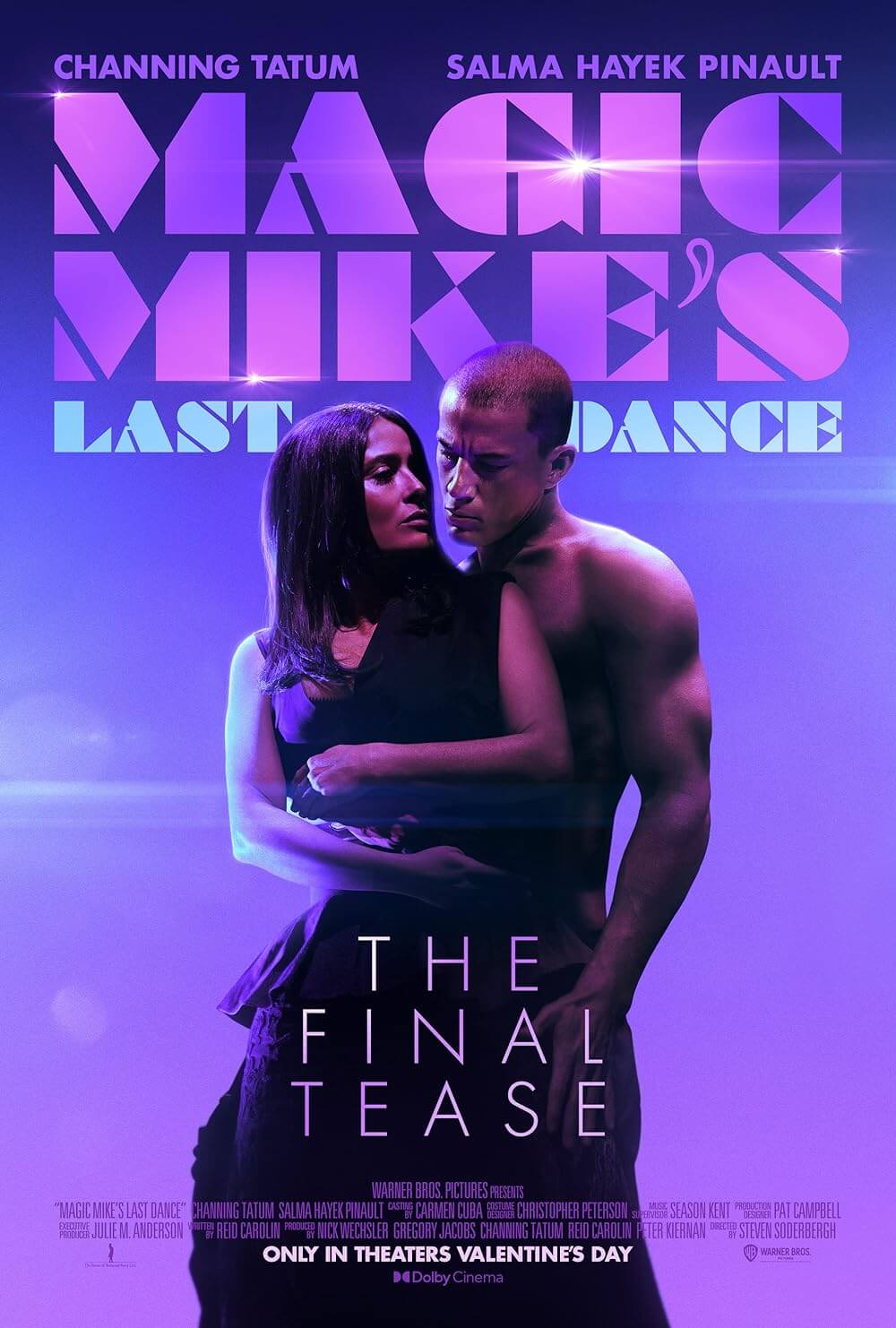

Magic Mike’s Last Dance

By Brian Eggert |

“It’s not what I really do,” Mike Lane says. He’s no longer the Magic Mike who strips for screaming women armed with dollar bills. With his custom furniture business dissolved, he flounders as a bartender at posh Florida parties. Though still played by Channing Tatum, now in his early 40s, Mike finds himself just scraping by when he gets an offer from Maxandra Mendoza. Played by Salma Hayek Pinault, Maxandra, the soon-to-be-divorcée from a media empire, awkwardly propositions him. He doesn’t do that either. But she’s willing to pay, so why not one last dance? Choreographed by Luke Broadlick, the ensuing dance, hypnotically performed and edited, plays out like an epic love scene. Afterward, Maxandra purrs, “You move like water.” And then she asks Mike a question that has plagued him since the first Magic Mike back in 2012: “Who are you?” He can only respond with the truth, “Um, I don’t know.” Magic Mike’s Last Dance attempts to answer that question, and in doing so, at once reframes and elevates the whole trilogy with this unique and surprisingly romantic entry in the series.

Helmer of the original, Steven Soderbergh returns as director after his longtime assistant, Gregory Jacobs, took over directing duties on 2015’s Magic Mike XXL—a lighter road-movie setup that proved irresistibly fun. Under Soderbergh, Magic Mike’s Last Dance distinguishes itself in altogether unexpected ways and ends the Magic Mike trilogy on a high note, if indeed it’s over. Penned by Reid Carolin, Tatum’s producing partner and screenwriter of the first two entries in this franchise, the third go-round finds Soderbergh laser-focused on fewer characters. But this second sequel is less interested in the themes of exploitation as a means for professional ambition—and it’s not even that concerned with stripping per se. Rather, it’s about the universality of dancing and its rare ability, like music, to compel human connections that defy the limitations of gender, language, nationality, and class. If that sounds like a lofty ambition for a series that began with a male stripper movie, so be it.

After making love—a term I do not use carelessly in this context—Maxandra propositions Mike again, albeit for something completely different. But she claims it’s “what you were meant to be doing all along.” Agreeing to pay him handsomely, the two hop on a plane to London, where Mike will stay with Maxandra, her teen daughter Zadie (newcomer Jemelia George), and their devoted if grumpy manservant Victor (acclaimed writer Ayub Khan Din, wonderfully deadpan and predictably knowing). Maxandra is the new owner of The Rattigan Theater, home to the long-running play, A Bird in a Gilded Cage—about a proper Englishwoman whose marriage prospects are limited to a rich jerk and a poor nice guy. In defiance of her future ex-husband, Maxandra wants Mike to direct, reimagining the play as a strip show so she can thumb her nose at her husband’s family, the Rattigans. She wants to tear down old traditions with a “wave of passion” and announce that women have more options than the stodgy stage dramas of yesteryear would imply. Rather, “A woman can be whatever she wants, whenever she wants,” Maxandra declares.

What unfolds feels like All That Jazz (1979) with a hint of a Soderbergh caper (the Ocean’s trilogy, Logan Lucky). Since the revised show ruffles all manner of feathers, Mike and his new dancers must charm a stuffy bureaucrat (Vicki Pepperdine), using methods that border on spycraft. Meanwhile, there’s a notable absence of characters from the earlier films—Matt Bomer, Joe Manganiello, Adam Rodriguez, and Kevin Nash appear briefly in a Zoom call scene. Instead, the film introduces the mostly anonymous group of new dancers in an audition montage, though most of them remain background players. More central is the company’s lead actress, Hanna (Juliette Motamed, pure energy, bound for stardom), who becomes the embodiment of a play where women had no choices but, in its new revised format, now celebrates women’s freedom to embrace every desire imaginable. But the film is about more than sexual liberation or female empowerment, it’s also about Mike and Maxandra finding outlets for their creativity.

What unfolds feels like All That Jazz (1979) with a hint of a Soderbergh caper (the Ocean’s trilogy, Logan Lucky). Since the revised show ruffles all manner of feathers, Mike and his new dancers must charm a stuffy bureaucrat (Vicki Pepperdine), using methods that border on spycraft. Meanwhile, there’s a notable absence of characters from the earlier films—Matt Bomer, Joe Manganiello, Adam Rodriguez, and Kevin Nash appear briefly in a Zoom call scene. Instead, the film introduces the mostly anonymous group of new dancers in an audition montage, though most of them remain background players. More central is the company’s lead actress, Hanna (Juliette Motamed, pure energy, bound for stardom), who becomes the embodiment of a play where women had no choices but, in its new revised format, now celebrates women’s freedom to embrace every desire imaginable. But the film is about more than sexual liberation or female empowerment, it’s also about Mike and Maxandra finding outlets for their creativity.

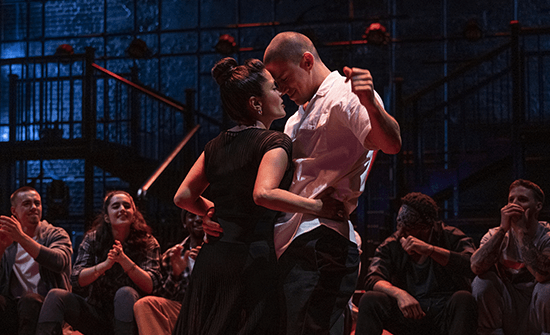

Although Magic Mike seemed less interested in the craft of dancing and Magic Mike XXL turned stripping into a campy passion project, Magic Mike’s Last Dance may feature scantily clad men dancing shirtless in various costumes, but the performances adopt an expressive meaning. Soderbergh shot and edited under his usual pseudonyms, Peter Andrews and Mary Ann Bernard, lending the film his sharp technical craft. But it’s Broadlick’s choreography and Pat Campbell’s stunning production design that makes the performances more than just another stripshow. Instead, Mike works through his complex relationship with Maxandra onstage, recreating his first dance and a later dramatic scene in the rain with a show-stopping performance. Dance can communicate what words cannot, and while Maxandra felt liberated by Mike’s initial dance, the final performance helps reconcile her feelings. Most endearing, Mike and Maxandra empower each other to create and become their fullest selves, while demonstrating what dance can transmit through movement and form.

Through it all, Magic Mike’s Last Dance is framed with a voiceover, performed by Zadie. Bookish and too young to watch some segments of the final performance, Zadie supplies commentary throughout on the historical and philosophical underpinnings of dance. These academic readings may seem superfluous to the onscreen drama unfolding, but they ultimately supply a method for understanding why Mike and Maxandra have such magnetism. “Dance seeks no meaning for its desires,” Zadie remarks. To be sure, there’s something innate and primal between the two, and the performers have chemistry to spare. Mike and Maxandra’s relationship becomes a layered dynamic, propelled by her unabashed belief in his talent, and his uncertainty about whether she’s committed to her cause or if this is another in a long line of unfinished projects. Hayek Pinault boasts a level of unbridled vibrancy, similar but dialed down next to her role in The Hitman’s Bodyguard (2017) and its sequel, yet also incredibly sexy. Tatum shows wounded pathos as Mike, whose feelings for Maxandra remain open and vulnerable, and there’s something sexy about that too.

Moviegoers should be thankful that Magic Mike’s Last Dance didn’t debut on HBOMax, the home of Soderbergh’s last few features, including Let Them All Talk (2020), No Sudden Move (2021), and KIMI (2022). Perhaps because the streamer has undergone some not-so-popular changes in the last year, Soderbergh’s latest arrives in theaters first, which is really where the sequel should be seen. Watching any Magic Mike film can only be improved by the group experience, and you’re less likely to get that at home on the couch. Still, though audiences may cheer during a few of the dance sequences, the film offers more insight and emotional pull than its predecessors. And its feminist themes, present in earlier entries but expanded here into a kind of philosophy, offer a welcome justification for nurturing desire without shame or judgment. No matter where you watch it (and you should), you’ll find a smart, sexy, and genuinely romantic movie that’s less interested in male strippers than the potential for dance to bring people together.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review