Magic in the Moonlight

By Brian Eggert |

Woody Allen’s protagonists often have bleak philosophical worldviews, insisting the universe is cold and empty and without wonder, save for the love with which we fill it. True of Allen’s protagonists from Annie Hall to Whatever Works, the presence of a god, or that which is beyond science and logic, is met with skepticism and incredulity, and often attributed to people’s need for hope, to quell their fears and let them cope with impending death. Such notions are an escape, like cinema. At the same time, Allen has long been fascinated with magic and the supernatural, and his interest in the subjects has emerged in Alice, The Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Scoop, and You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger. But as an amateur illusionist, Allen has always been unconvinced of authentic magic, which by extension overlaps with his religious skepticism, and so his views clearly align with his protagonist in Magic in the Moonlight, Allen’s forty-fourth picture.

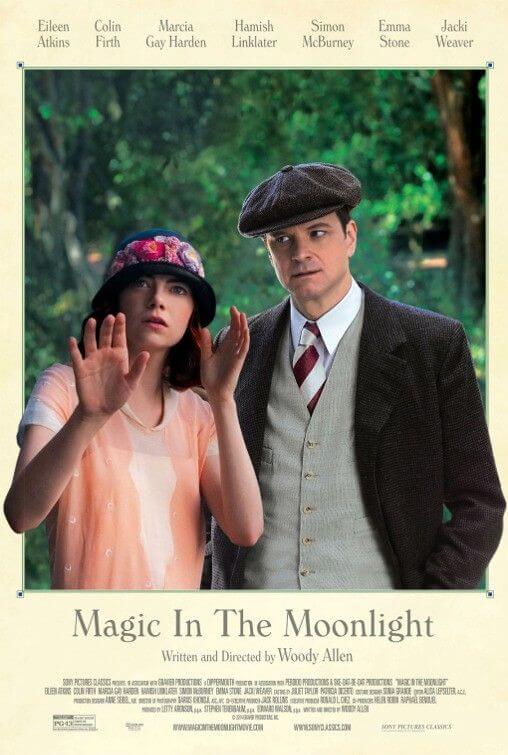

Colin Firth plays resident cynic and acerbic disbeliever Stanley Crawford, a London-based illusionist who performs under the “Oriental” stage guise Wei Ling-soo throughout Europe in 1928. (Stanley is also Allen’s homage to William Ellsworth Robinson and his Chinese pseudonym Chung Ling-soo, who famously died when he failed to catch a bullet in his teeth.) In his spare time, Stanley uses his considerable talent to debunk false mystics and palm-readers, and his obsession with logic and science has carried into his dispirited love life. A friend and fellow magician Howard (Simon McBurney) tells Stanley about a medium, a young woman named Sophie Baker (Emma Stone), who, along with her business manager mother (Marcia Gay Harden), has convinced a family of wealthy industrialists in the south of France of her other-worldly talents. Intrigued, Stanley accepts Howard’s proposal to expose the young psychic as a fraud, if only because his charming aunt (Eileen Atkins) lives nearby.

Once there, he finds susceptible widow Grace (Jacki Weaver) and her son Brice (Hamish Linklater), who dotes on the pretty Sophie and vows to marry her, all of them taken by Sophie’s ability to tell them things about themselves that no one else could possibly know. Moreover, Sophie helps Grace speak to her late husband in a séance as both Howard and Stanley watch, both of them unable to figure out her trickery. Meanwhile, Stanley probes Sophie with a cutting and sarcastic line of questioning, until she begins to pick up “psychic vibrations” about him and his aunt’s respective secret pasts, and all at once, Stanley’s ability to identify swindlers “from the séance table to the Vatican and beyond” is impeded. But even if his time with Sophie opens him up to the possibility of more in the universe outside of hard facts, Stanley’s belief in love and romance isn’t included in his sudden openness, much to the dismay of Sophie, who’s taken a shine to her disbelieving spectator.

Allen’s virtuoso wordsmithing is present in Magic in the Moonlight as one would expect, and it’s enlivened by early twentieth-century vocabulary, his usual discussions of Freud and Nietzsche, and comprised of long speeches and exchanges between usually no more than two or three characters, all of whom voice their stance on this or that subject, mostly relating to their belief or lack thereof in the supernatural. There’s a persistent debate throughout the film about systems of belief and how they serve as a coping mechanism to get through this hard, unforgiving thing called life. Little of what happens in the film is situational, and as a result, it has a stage-like quality. Indeed, Magic in the Moonlight may be one of Woody Allen’s films that is most attuned for stage adaptation since September or even Interiors. The performances, exaggerated for comic effect, are even calibrated for theatricality. Firth, more than his costars, seems to shout his pronouncements as if he’s trying to reach the back row; still, he’s appealing in the role as a stuffy Doubting Thomas. Stone, meanwhile, remains adorably girlish, her face lit up like a Christmas tree from start to finish.

Shot on textured 35mm film stock by Darius Khondji, Allen’s director of photography on his top-performing Midnight in Paris, the film captures those Cote d’Azur settings in all their 1920s glamor—including sharp automobiles, ravishing seaside vistas, and gorgeous costumes by Sonia Grande. Production designer Anne Seibel realizes lively, flowered sets so strikingly lit and drenched in period airs that the story’s rather simple, underwhelming quality is enhanced by the Riviera surrounding. Certainly, Magic in the Moonlight belongs among Allen’s so-called European travelogue films as of late, including his London fare (Match Point, Cassandra’s Dream), Spain (Vicky Cristina Barcelona), Italy (To Rome with Love), and San Francisco (Blue Jasmine). But then, Allen has always made his environments a major influence on the narrative of his films.

And like Allen’s weaker offerings set away from his New York City stomping grounds (the ho-hum To Rome with Love and You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger come to mind), Magic in the Moonlight is a modestly romantic trifle. It’s concerned with location, location, location, and not much else. Sustaining the mystery about whether or not Sophie is actually a seer or dreaming up a series of impossibly romantic situations isn’t Allen’s concern; nor is creating a memorable ensemble of supporting characters (everyone but Firth, Stone, and Burney seem like filler in the scenery). Fortunately, Firth and Stone are delightful in their own right, with the former occupying a textbook misanthrope of Allen ilk, the latter a frivolous sort whose wide- and bright-eyed features give her the plausible look of someone with a sixth sense. In all, the film is a serviceable lark for its brief runtime, and contains enough minor pleasures to justify an equally minor endorsement.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review