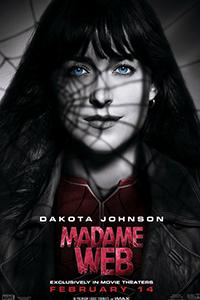

Madame Web

By Brian Eggert |

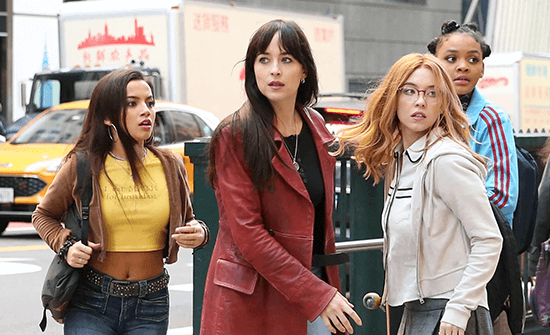

Even after recent superhero movies have lowered standards, Madame Web is among the worst adaptations of a Marvel Comic ever made. Another entry in Sony’s Spider-Man spinoff universe—including Venom (2018) and its 2021 sequel, Morbius (2022), and coming soon, Kraven the Hunter—the movie is a spectacular mess. Dakota Johnson, playing an obscure and lesser-known character in Spider-Man lore, stars as a New York paramedic who develops spider-based precognitive abilities, giving her the foresight to protect three future superheroes from a dastardly spider-centric villain. But nearly everything about the production—the performances, character development, screenplay, camera movements, and editing—suggests those involved had other things on their minds besides telling a good story. They were probably busy fulfilling the demands of a corporation determined to squeeze every drop of potential out of their intellectual property. So, it’s less about thoughtfully translating a character to the big screen than supplying companies such as Pepsi with a place to hang their product placements and commercial tie-ins.

The movie plays like the chaotic result of copious notes from executives and marketing committees, while director S. J. Clarkson’s work alongside three other credited writers feels beside the point. Unlike the protagonist, whose second sight allows her to make choices to select the best possible future, the filmmakers have little creative wiggle room. Everyone involved is adhering to the blueprint, no doubt based on an algorithmic model capable of predicting maximum audience satisfaction, and then informed by an AI screenplay analysis tool that determines whether the product will earn a positive return on Sony’s $80 million investment. Madame Web may look quite good on paper according to this hypothetical AI software. But, as with most Hollywood formulas, the details matter. And anyone who’s used AI in creative matters knows there’s always something not quite right about the result. Unfortunately, few of the details here coalesce into a coherent or compelling structure; instead, it’s embarrassing from start to finish.

With a level of superhero storytelling not seen since the early 2000s, Madame Web takes place, curiously enough, in 2003. Looking back, the superhero movies of that year include Ang Lee’s Hulk, the Ben Affleck version of Daredevil, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. And it’s as though Clarkson—who makes her feature debut after an impressive career directing television—watched each disastrous example for inspiration. A prologue set in the Peruvian jungle in 1973 establishes that Cassie Webb is born after her mother (Kerry Bishé), who was researching rare spiders, dies in childbirth. Thirty years later, Cassie (Johnson) drives ambulances with her partner, Ben Parker (Adam Scott). During a rescue, she falls into the river while inside a car, and her near-death experience activates something in her mind—she can now see brief glimpses of possible futures, which register as déjà vu at first. Part of what she sees is Ezekiel Sims (Tahar Rahim), a mysterious man in a Spider-Man-esque suit, killing off three future Spider-Women—Julia (Sydney Sweeney), Mattie (Celeste O’Connor), and Anya (Isabela Merced), who, at present, are still powerless teenagers. Cassie resolves to intervene and help the girls with her clairvoyant powers.

The setup draws inspiration from science-fiction concepts established in Philip K. Dick’s literature about predestination versus determinism, albeit without the author’s intelligence or vision. Similar to the protagonist in Dick’s novel The World Jones Made or the short story “The Minority Report” (both from 1956), Cassie can see various possibilities before they happen and make the perfect decision for the moment to thwart Ezekiel. But Madame Web’s characters, narrative, and execution fail to make the idea compelling. The teens, each with absent parents like Cassie, rely on her as a makeshift denmother and protector. They’re rambunctious and irresponsible, but they’re little more than three damsels whose eventual roles as Spider-Women remain unrealized. Johnson plays Cassie with a flatness that suggests she’s going through the motions for her paycheck, which will sustain her until she can do something more meaningful with Luca Guadagnino or some other more artistically inclined filmmaker.

The setup draws inspiration from science-fiction concepts established in Philip K. Dick’s literature about predestination versus determinism, albeit without the author’s intelligence or vision. Similar to the protagonist in Dick’s novel The World Jones Made or the short story “The Minority Report” (both from 1956), Cassie can see various possibilities before they happen and make the perfect decision for the moment to thwart Ezekiel. But Madame Web’s characters, narrative, and execution fail to make the idea compelling. The teens, each with absent parents like Cassie, rely on her as a makeshift denmother and protector. They’re rambunctious and irresponsible, but they’re little more than three damsels whose eventual roles as Spider-Women remain unrealized. Johnson plays Cassie with a flatness that suggests she’s going through the motions for her paycheck, which will sustain her until she can do something more meaningful with Luca Guadagnino or some other more artistically inclined filmmaker.

Meanwhile, the villain’s motivations are murky at best. Performed by the French actor Tahar Rahim with a baffling accent, most of which sounds ADRed, Ezekiel wants the girls dead because he has seen his grim future where the Spider-Women eventually kill him—though, there’s no further explanation. Aside from wanting to forestall his death, what Ezekiel plans to achieve with his vague powers is unclear. What is his evil Master Plan, and why were the future Spider-Women attacking him? We never find out. Similarly, some Peruvian spider-guy explains to Cassie that her mind has “infinite potential,” but the full scope of her powers feels unclear. And the flash-forwards to Spider-Women never allude to how they gained their powers, nor the nature of their abilities (they use energy blasts and robo-arms). In this, the movie expects comic-savvy audiences to come equipped with that knowledge, leaving everyone else thoroughly confused. Besides plot details, the emotional beats, too, never land. Take the tension between Cassie and her mother, whom she resents for her absence. Cassie’s sense of abandonment isn’t established enough to pay off emotionally when she reconciles with her mother later in the Spider Realm (or whatever it’s called).

Also oppressively confusing is Madame Web’s visual execution. Although some brief nods to Martin Scorsese’s frenzied ambulance drama Bringing Out the Dead (1999) and Steven Spielberg’s prescient Minority Report (2002) suggest there was some intention behind the aesthetic, the rest is jumbled. Cinematographer Mauro Fiore uses upside-down and twisting camera movements to enliven the proceedings, but there’s no consistent use of them, making each choice feel impulsive and flailing. Editor Leigh Folsom Boyd adopts the motif of broken glass to evoke a spider’s web, working in fractured images and shard-like film segments, and she presents them in a jarring succession of cuts framed by embarrassingly bad CGI webs. The brief glimpses of the future Spider-Women look downright silly, too, as though the filmmakers resolved to use 2003-era technology to render them. The chases and fights prove mostly unintelligible, and since the viewer is strained to care about anything happening onscreen, the action feels even more hollow than it looks.

When the climactic battle unfolds against the neon Pepsi-Cola sign in Queens, it’s unmistakable that Madame Web exists as a product first and a commercial artwork second. That bitter pill might be easier to swallow if the outcome weren’t so incompetent. This manner of lazy, slipshod filmmaking plays only to a shut-your-brain-off-and-enjoy-it audience, uncritical of Hollywood delivering superhero movies of the lowest possible quality. But even on those resigned terms, it’s insulting. There’s no care or passion behind it, making similar products from the MCU and DCEU seem like fine art by comparison. Madame Web doesn’t even have the courtesy of being passively awful; it’s an active, incessant loathsomeness that permeates almost every scene and twists the viewer into knots for the torturous 116-minute runtime. And when it’s not naggingly dreadful, it’s simply not entertaining, not even ironically so, which may be its worst characteristic of all.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review