Mad Max: Fury Road

By Brian Eggert |

A marvelous degree of craziness and discipline was required to make Mad Max: Fury Road, Australian director George Miller’s reimagining of, or perhaps a belated sequel to, his original Ozploitation trilogy. Three decades after taking down Blaster in Thunderdome, Mad Max returns for the fourth, most inventive and bombastic entry in this series of post-apocalyptic vehicle wars, a completely bonkers and titillating piece of entertainment that has no recent equal. Indeed, the Fast and Furious series looks populated by slogging pacifists in comparison. Tom Hardy now occupies Mel Gibson’s well-worn leather duds as the titular Max Rockatansky, a former cop turned reluctant road warrior on Miller’s unforgiving, barren, but beautifully conceived highways of carnage. This desolate world comes fuelled by adrenaline, soiled with gruesome ultra-violence, and propelled by unbelievably outrageous high-speed chases, unlike anything you’ve ever seen. After defining the post-apocalyptic subgenre in 1979 with the original Mad Max, and its two sequels, Miller, now in his seventies, shows no signs of slowing based on this decadent display of practical effects, impressive pyrotechnics, and exhilarating showmanship.

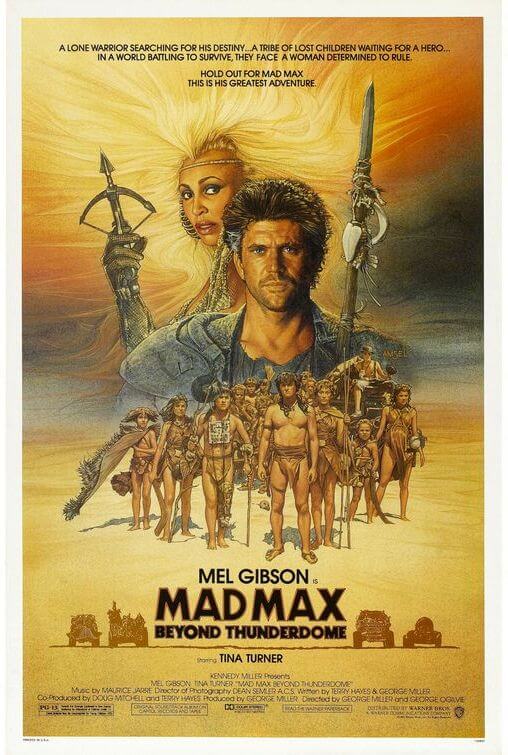

In recent years, Miller’s name has been associated with more child-friendly material, such as Babe: Pig in the City (1998), Happy Feet (2006), Happy Feet Two (2011), and some development on Warner Bros.’ abandoned 2008 production of a “Justice League” superhero film. But in the years after Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), Miller fed rumors of another Mad Max sequel. News of countless setbacks, false starts, delays, budgetary quarrels, and casting rumors have filled Hollywood insider trades for more than a decade—going back to when Gibson was still set to reprise the role that made him a star. As time went on and Gibson got older, as early as 2009, Miller recast the role with Hardy, hired Charlize Theron as Hardy’s costar, and began scouting locations. Filming didn’t begin until 2012, and lasted upwards of 120 days in Namibia, plus reshoots the following year, with a reported budget of $150 million, a far deal greater than the paltry budgets used to make the original three. And despite Fury Road looking and feeling more expensive, more over-the-top, and more kick-ass than its predecessors, it still feels like a part of the same universe Miller created all those years ago.

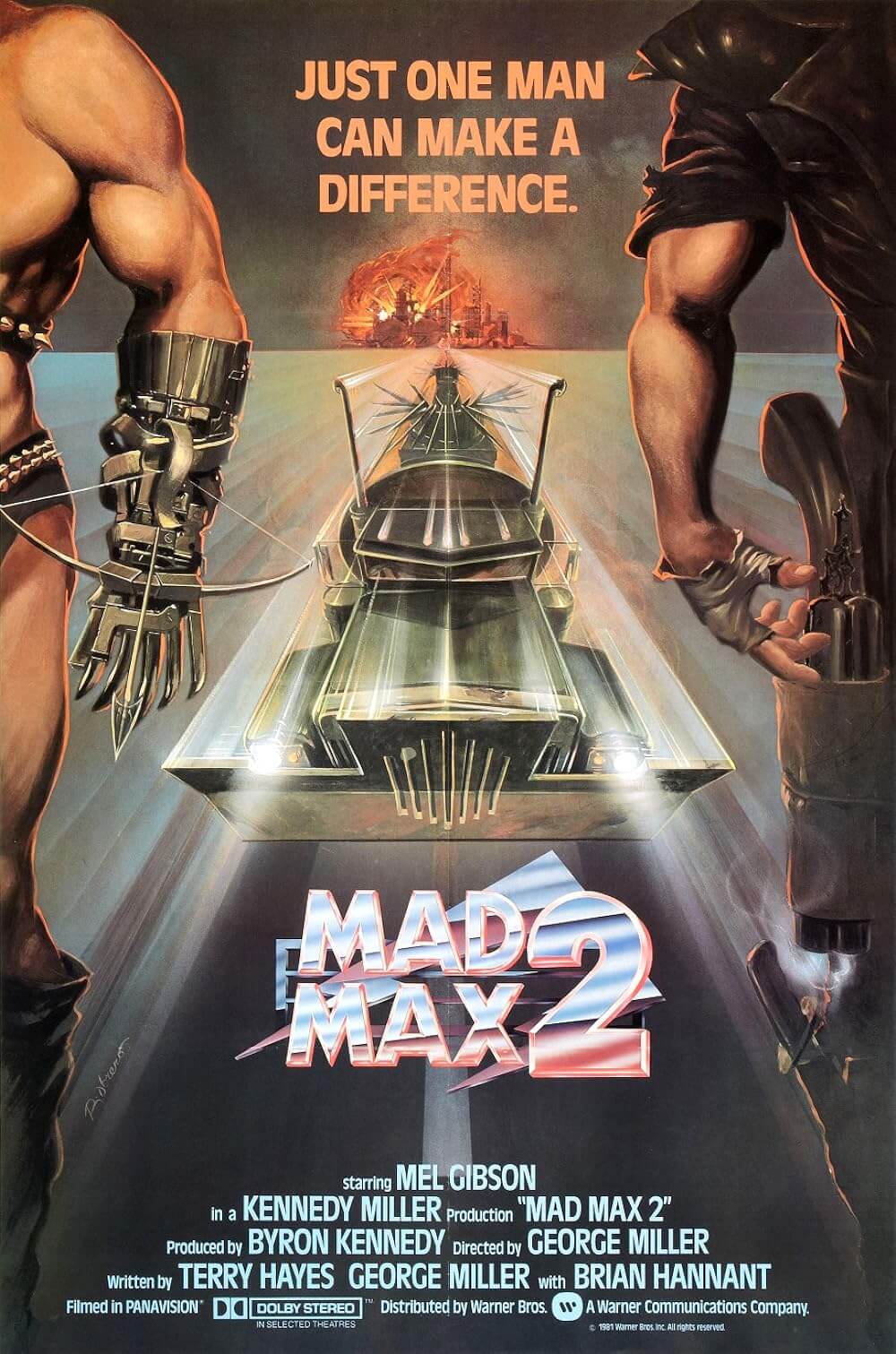

To be sure, Mad Max: Fury Road is a far more complex experience visually than the rather trim Mad Max, yet its narrative heft feels more grandiose and adult than the family-friendly outing Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Unavoidably and quite complementarily, the film earns its close association to the second and best in the series, The Road Warrior (1981), which, like this latest entry, occupies its runtime with what amounts to a single, film-long chase sequence. However conceptually simple Fury Road’s actionized chase scenario may seem on the surface, Miller and his cowriters (Nico Lathouris and comic author Brendan McCarthy) layer the material with heavy themes of redemption, revolution, and buried memories. Each of Miller’s Mad Max films have had their own unique pitch and themes: the first concerned tragedy and revenge, the stripping-down of Max’s humanity; the second displayed a glimmer of hope in our anti-hero within his otherwise thankless world; and the third found him regaining his human sympathy by rescuing a group of children.

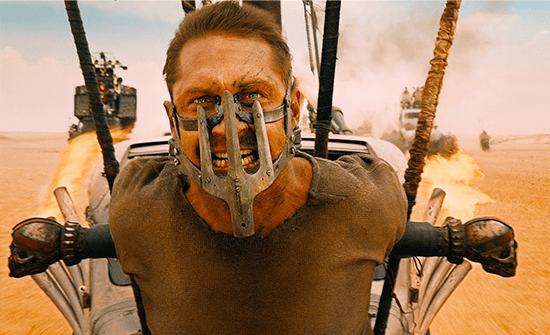

Mad Max: Fury Road finds the anti-hero more animal-like, a mad dog survivor realized by Hardy with paranoid eyes and convulsive jolts into his tragic past. “My world is reduced to a single instinct: survive,” he says in the opening narration, which recalls a more personalized version of the prologue in The Road Warrior. Max moves with a kinetic ferocity, almost on autopilot, especially early on when Hardy’s considerable physical presence is enhanced by Miller running the film speed at a higher rate, as if Max has been electrified. During the fracas, Max, who remains nameless for much of the picture, receives flashes from his past, and images of his daughter’s death haunt him at key moments. He seems to have buried these images so deep that he no longer understands their meaning, to the extent that he even looks confused by their appearance in his mind. “As the world fell it was hard to know who was more crazy. Me, or everyone else,” he observes. Only as the story progresses, and Max finds someone to fight alongside, do those images become clearer. Although, refreshingly, Miller never explains their origin through clumsy expositional dialogue or a flashback; Max’s understanding comes by way of a calmer, more gathered expression behind Hardy’s piercing blue eyes.

Mad Max: Fury Road finds the anti-hero more animal-like, a mad dog survivor realized by Hardy with paranoid eyes and convulsive jolts into his tragic past. “My world is reduced to a single instinct: survive,” he says in the opening narration, which recalls a more personalized version of the prologue in The Road Warrior. Max moves with a kinetic ferocity, almost on autopilot, especially early on when Hardy’s considerable physical presence is enhanced by Miller running the film speed at a higher rate, as if Max has been electrified. During the fracas, Max, who remains nameless for much of the picture, receives flashes from his past, and images of his daughter’s death haunt him at key moments. He seems to have buried these images so deep that he no longer understands their meaning, to the extent that he even looks confused by their appearance in his mind. “As the world fell it was hard to know who was more crazy. Me, or everyone else,” he observes. Only as the story progresses, and Max finds someone to fight alongside, do those images become clearer. Although, refreshingly, Miller never explains their origin through clumsy expositional dialogue or a flashback; Max’s understanding comes by way of a calmer, more gathered expression behind Hardy’s piercing blue eyes.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. In the distant post-apocalypse of Miller’s vision, human beings are the new precious commodity. Forget fuel and ammunition; Gas Town and the Bullet Farm have that covered. Only sand-swept roads and dunes flourish in the Wasteland, leaving humans with no chance unless they suffer under the Citadel—a pair of buttes standing alone in the desert, inhabited by the cultish ruler on high, the fearsome Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne, who played the marauding Toecutter, presumably no relation, in the original Mad Max). His body serves as a metaphor for the entire landscape, scorched and harsh, patched together by body plates, pieces of old hardware, breathing tubes, and a toothy mask. What a horrific kingdom he has made, where he controls his slaves by regulating the water supply, and where his beautiful wives are branded as property and locked in a vault. Elsewhere in the Citadel, he keeps rotund mothers strapped to pumps to deliver valuable breastmilk for trade, and their human babies, his sires, provide the capital for an army of devoted subjects. Should an unlucky Wasteland survivor find himself captured by the ruler’s personal army of War Boys, he’d be tattooed with his blood type and organ status, and hanged upside-down as a human blood bag for Immortan Joe’s weak or dying devotees.

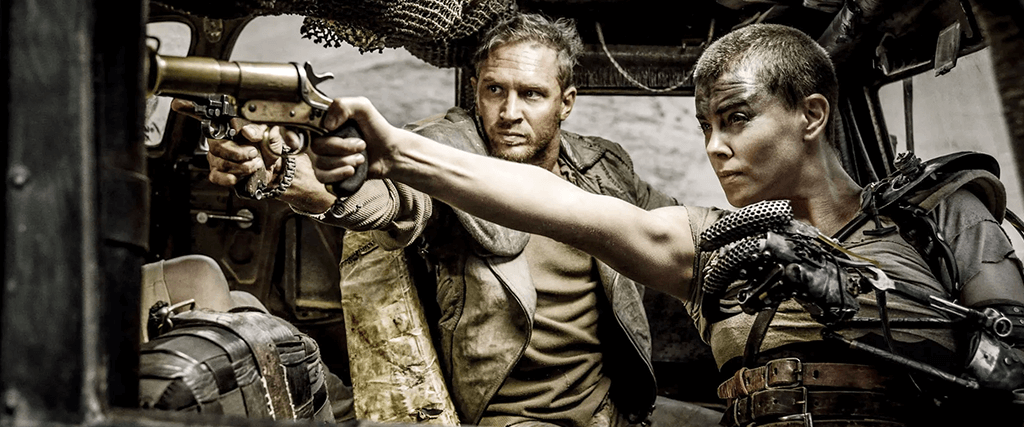

One such “blood bag” is Max himself, interned in the first scene and hung to fuel Nux (Nicholas Hoult), one of Immortan Joe’s shaved, branded, white-painted, and skeleton-faced fanatical soldiers. Following his leader’s abstract religion, Nux has been promised glory and another life in Valhalla should he faithfully serve Immortan Joe (and spray his mouth silver before the moment of death). Enter the noblewoman-badass Imperator Furiosa (Theron), who’s entrusted to drive a War Rig on a fuel run, but instead detours with Immortan Joe’s escaped wives to liberate them from captivity. Miller’s flair for wild names carries on with the wives: Splendid, Capable, Cheedo the Fragile, and Toast the Knowing. These wives look like a gaggle of super-models and first appear in a wet fantasy scene. However, they’re gradually empowered throughout the chase. In response, Nux straps a metal-masked Max, muzzled like a feral beast, onto the front grille of his car and, along with a small army of souped-up vehicles, pursues glory to recoup Immortan Joe’s “property”. For the next two hours, the ensuing chase sequence, driven by Miller’s breakneck pace, offers only a few fleeting seconds of reprieve from the mayhem.

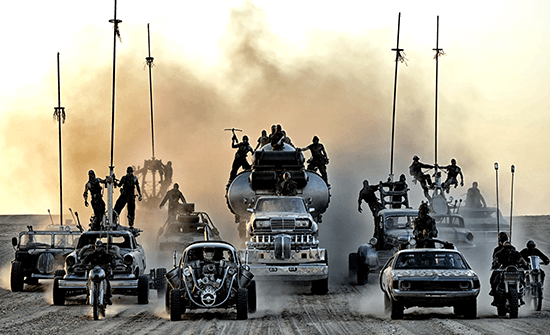

And oh, what mayhem—what glorious, delightfully orchestrated mayhem. Supposedly, ninety percent of the effects and stunts were achieved without CGI, and based on the result, it looks to be true. A staggering level of pyrotechnics and car wrecks appear to have been achieved with practical effects and stuntmen, something of a rarity in today’s market of computer-generated aerobatics in Fast and Furious. Ever the tactile tactician, Miller captures every angle imaginable and at varying film speeds thanks to the feverish work of cinematographer John Seale, whose frame vibrates with the speed of his car-mounted cameras. Still, never is there a moment where the clarity of the situation or shot-by-shot logic is questioned; rather, the impossibly fast-paced momentum proceeds with a shocking and almost unheard-of degree of precision, all of it given an incredible dose of aural energy thanks to Dutch musician Junkie XL’s score. Throughout, Miller’s editor and wife, Margaret Sixelour, allows us to briefly appreciate Colin Gibson’s intricate production design and Jenny Beavan’s imaginative costumes. With every new shot, there are more details to savor that require repeated viewings to fully appreciate: the slave ship whose sole purpose is to provide the chase with drums and riffing from a heavy metal, flame-spewing guitar; the pole-riding daredevils who swing from one vehicle to another, performed by members of Cirque du Soleil; the grotesque growths, piercings, and body markings displayed by post-apocalyptical mutants; and the believable robotic forearm attached to Furiosa.

And oh, what mayhem—what glorious, delightfully orchestrated mayhem. Supposedly, ninety percent of the effects and stunts were achieved without CGI, and based on the result, it looks to be true. A staggering level of pyrotechnics and car wrecks appear to have been achieved with practical effects and stuntmen, something of a rarity in today’s market of computer-generated aerobatics in Fast and Furious. Ever the tactile tactician, Miller captures every angle imaginable and at varying film speeds thanks to the feverish work of cinematographer John Seale, whose frame vibrates with the speed of his car-mounted cameras. Still, never is there a moment where the clarity of the situation or shot-by-shot logic is questioned; rather, the impossibly fast-paced momentum proceeds with a shocking and almost unheard-of degree of precision, all of it given an incredible dose of aural energy thanks to Dutch musician Junkie XL’s score. Throughout, Miller’s editor and wife, Margaret Sixelour, allows us to briefly appreciate Colin Gibson’s intricate production design and Jenny Beavan’s imaginative costumes. With every new shot, there are more details to savor that require repeated viewings to fully appreciate: the slave ship whose sole purpose is to provide the chase with drums and riffing from a heavy metal, flame-spewing guitar; the pole-riding daredevils who swing from one vehicle to another, performed by members of Cirque du Soleil; the grotesque growths, piercings, and body markings displayed by post-apocalyptical mutants; and the believable robotic forearm attached to Furiosa.

In fact, Furiosa may just steal the film from under Max’s nose after their characters meet and join forces on the road. A ferocious driver and brutal fighter, Furiosa represents a rare thing in the Mad Max franchise: a strong female character. She doesn’t trust Max at first, having experienced first-hand the savagery of men in the post-apocalypse. Theron’s troubled, glassy eyes contain all the emotional charge needed in this vicious film, and they remind us of Renee Falconetti’s sorrowful expressions in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Her quest to transport the child-bearing female captors to salvation is immediately empathetic, while Max’s hardened exterior seems as pitiless as the world he inhabits. Hardy, meanwhile, is perfect in his role; it’s impossible to imagine another modern actor recreating Mad Max so effectively. He’s capable of rendering both Max’s animalistic and nobler scenes with careful calibration of his face. “You know hope is a mistake,” he tells Furiosa in one of their few audible exchanges. Dialogue is a luxury in a film like this, and Miller has said he intended the film to be such a visual experience that it could play in foreign countries without subtitles. Fortunately, actors of Hardy and Theron’s caliber need only brief glances to communicate a wealth of understanding between the two characters during the film’s never-ending pursuit.

While it remains somewhat unclear whether Miller meant Mad Max: Fury Road as a sequel or a reboot, labels such as these don’t matter when the result is so singular, so insane, so eye-poppingly unique. What remains impressive for Miller is how, even after his recent family fare, he switched back to a grindhouse-quality exhibition that never pulls its punches the way his divisive, Hollywoodized Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome did—in fact, Mad Max: Fury Road may be the most merciless entry in the series. And even though the film exists in a nihilistic and violent world, its worldview retains a surprising degree of hope to prevent the experience from becoming a punishing or exploitative one. Instead, the viewer becomes swept up in the forward-moving narrative impetus, thrilled to audible gasps by Miller’s wonderfully excessive parade of stunts and effects, each more impressive and more fantastically outlandish than the last. With Miller’s promise that a sequel entitled Mad Max: Furiosa has already been written, and Hardy confirming he’s signed to star in three sequels, Mad Max: Fury Road is certainly the continuation and possibly the new beginning of a great legacy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review