Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome

By Brian Eggert |

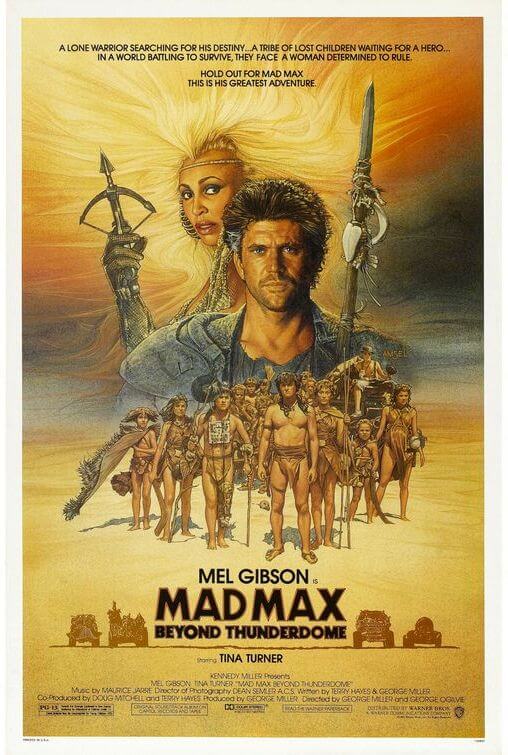

Combining elements of Spaghetti Westerns, J.M. Barrie lore, and his own love for post-apocalyptic road wars, Australian director George Miller delivered the third and most divisive entry in his series with Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Miller’s first Hollywood production, financed and distributed by Warner Bros. after his successes with Mad Max (1979) and The Road Warrior (1981), hit theaters in 1985 and received praise for Miller’s virtuoso orchestration of the film’s impressive setpieces, exciting action, and pure imagination. Co-directing alongside George Ogilvie, Miller also injects rather suspect humor and humanity into his otherwise grim, hopeless vision for the future, and he presents the most crowd-pleasing, least challenging film of his original trilogy. While technically brilliant and visually impressive, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome can leave an audience dizzy over its three distinct, incongruous acts, each of which occupies its own tonal and almost incompatible characteristic. Overall, it’s an entertaining entry in the franchise, though the film is also the least sure of what it wants to be.

After his longtime friend and co-producer Byron Kennedy, who produced and played a major role in shaping the previous two Mad Max films, died in 1983 in a helicopter accident, Miller proceeded with Warner Bros.’ offer to make a sequel to The Road Warrior using a Hollywood-grade budget and resources. Alongside Ogilvie, with whom Miller co-directed the television miniseries The Dismissal (1983), they proceeded to shoot on locations throughout Southern Australia and near Sydney. By this time, Mel Gibson’s career was ready to explode, if it hadn’t done so already. He was still starring in primarily Australian imports that were very successful in the U.S., such as The Bounty (1984) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). But Lethal Weapon was just two years away, and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome would help secure him the iconic role of Martin Riggs in that Warner Bros. franchise. From there on out, Gibson would be Mr. Hollywood. Still, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome arrived in the summer of 1985, just a week after the box-office giant Back to the Future. While the film performed well enough to triple its $12 million budget in returns, it was overshadowed by more successful titles. Most viewed the sequel as an admirable letdown, whereas few (such as Roger Ebert) championed Miller’s vision.

Ever the film buff, Miller worked with his co-writer Terry Hayes to further steep the Mad Max character into established cinematic mythology. Mad Max had been an homage to chase movies like Bullitt (1968) and The Wild One (1954); The Road Warrior had been an homage to classic Western gunslingers like characters in Shane (1953) and Japanese samurais like in Yojimbo (1960), both of which present characters that are rugged outlaws who become reluctant heroes. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome would further associate Max with filmic anti-heroes, specifically Clint Eastwood’s character “The Man with No Name” in Sergio Leone’s trilogy, most of all The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Indeed, Max is specifically referred to as “The Man with No Name”, making the comparison impossible to avoid. Also unavoidable is Max’s vague, almost Christ-like quality. He first appears in the desert with camels and a cart in tow, his long hair sporting streaks of gray at his temples. But rather than the vengeful killer from Mad Max or even the clever scavenger in The Road Warrior, Max becomes a merciful savior of pig-killers, grotesques, and forgotten children.

Ever the film buff, Miller worked with his co-writer Terry Hayes to further steep the Mad Max character into established cinematic mythology. Mad Max had been an homage to chase movies like Bullitt (1968) and The Wild One (1954); The Road Warrior had been an homage to classic Western gunslingers like characters in Shane (1953) and Japanese samurais like in Yojimbo (1960), both of which present characters that are rugged outlaws who become reluctant heroes. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome would further associate Max with filmic anti-heroes, specifically Clint Eastwood’s character “The Man with No Name” in Sergio Leone’s trilogy, most of all The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Indeed, Max is specifically referred to as “The Man with No Name”, making the comparison impossible to avoid. Also unavoidable is Max’s vague, almost Christ-like quality. He first appears in the desert with camels and a cart in tow, his long hair sporting streaks of gray at his temples. But rather than the vengeful killer from Mad Max or even the clever scavenger in The Road Warrior, Max becomes a merciful savior of pig-killers, grotesques, and forgotten children.

Maurice Jarre’s wonderful percussive score echoes clanking metal as Gibson’s wandering Max enters the post-apocalypse’s teeming free enterprise capital, Bartertown. His camel and cart stolen by a familiar pilot and child (Bruce Spence and Adam Cockburn), Max enters on foot. In the methane-fuelled Bartertown, peddlers sell everything from Max’s own camels to radioactive water, and it’s ruled from on high by Aunty Entity (Miss Turner), who remains at the mercy of the subterranean world beneath Bartertown’s surface. Underneath lies a gas refinery run on pig excrement, its leader a clever dwarf named Master (Angelo Rossitto), ever accompanied by his giant bodyguard Blaster (Paul Larsson)—together, they are Master Blaster, brains and brawn. Aunty Entity wants Blaster dead and Master’s smarts to herself, and so she strikes a bargain to return Max’s cart and camel if he kills off Master Blaster in Bartertown’s “Thunderdome” arena. Max agrees and heads undercover into the methane operation to size up Blaster’s weaknesses; while there, he befriends a convict (Robert Grubb) who was arrested and branded “Pig Killer” after trying to steal a hog to feed his family. Later, the redeemer Max grants the thief escape, if not absolution for his crime.

Stealing the entire film is the cage match fight sequence between Max and Blaster, wherein the two men are bungeed inside a metal dome pen, on the outside of which spectators cling and cheer. The combatants leap around each other, bouncing, reaching for weapons such as a spear or chainsaw, in what Aunty Entity hopes will be a battle to the death. Preceded by a carnival barker-like announcement from Edwin Hodgeman’s contorted Dr. Dealgood (“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls… Dyin’ time’s here.”), the Thunderdome fight is a thrilling sequence that belongs at the end of a film, not the beginning. In the course of the fight, Max discovers that the masked Blaster is actually a mentally disabled man, and being merciful, he refuses to comply with the law of “Two men enter, one man leaves” and finds himself exiled. Aunty Entity has Blaster killed and consigns Master to a cage, where he’s ordered to keep the methane flowing, less he be fed to pigs. By this time, viewers will have noticed how Miller has established another parallel to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Mad Max is the Good, Aunt Entity is the Bad, and Master is the Ugly. In keeping with this parallel, Master becomes vaguely sympathetic, while Max and Aunt Entity form a mutual respect.

Meanwhile, near death, Max is picked up by a group of children, and all momentum built up in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome to this point comes to a screeching halt. They survive in a sort of grotto, stranded there since their plane crashed during the height of the apocalypse. The eldest girl, Savannah Nix (Helen Buday), maintains a tradition of oral history, to which the children chant in remembrance of their fallen pilot, who had promised to return and rescue them but never did. They believe Max is that pilot, and he’s come to take them to the prophesied “Tomorrow-morrow Land”—their name for Sydney. When Max tries to tell them the truth, that the only populated area nearby is Bartertown, several go looking, and he must follow to rescue them. One could conceive that Steven Spielberg watched Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome before filming Hook (1991), and borrowed elements of this segment for that film, which also involves a frustrated adult contending with children who have created their own myths and customs in place of any passed-down social structure. To be sure, the Lost Boys from Spielberg’s film speak in the same broken cadence that the surviving children speak here (“Still in all, every night we does the tell, so that we ‘member who we was and where we came from.”), a way of talking that anticipates the distant future-speak in Cloud Atlas (2012).

Meanwhile, near death, Max is picked up by a group of children, and all momentum built up in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome to this point comes to a screeching halt. They survive in a sort of grotto, stranded there since their plane crashed during the height of the apocalypse. The eldest girl, Savannah Nix (Helen Buday), maintains a tradition of oral history, to which the children chant in remembrance of their fallen pilot, who had promised to return and rescue them but never did. They believe Max is that pilot, and he’s come to take them to the prophesied “Tomorrow-morrow Land”—their name for Sydney. When Max tries to tell them the truth, that the only populated area nearby is Bartertown, several go looking, and he must follow to rescue them. One could conceive that Steven Spielberg watched Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome before filming Hook (1991), and borrowed elements of this segment for that film, which also involves a frustrated adult contending with children who have created their own myths and customs in place of any passed-down social structure. To be sure, the Lost Boys from Spielberg’s film speak in the same broken cadence that the surviving children speak here (“Still in all, every night we does the tell, so that we ‘member who we was and where we came from.”), a way of talking that anticipates the distant future-speak in Cloud Atlas (2012).

In the final act, Max sneaks into Bartertown to rescue the children and escapes along with Master and the “Pig Killer” on a truck that runs on train tracks, and leaves the town in flames. Enraged, Aunty Entity pursues. Max defends the children in an expertly shot high-speed chase. The film enters territory established in Mad Max and bested by The Road Warrior, although a few wildly bombastic stunts remain memorable. Nevertheless, high-octane crashes, explosions, and mayhem result in little onscreen death, with several despicable villain characters surviving the fracas if only to sustain the film’s commercial appeal. It’s also a notable kitschy sequence whose action is laden with a few laughs (at one point, Max commandeers a dragster covered in a palomino hide). Eventually, Max and company find the pilot and his child in the film’s opening scene, and they fly the children away. They live on to tell stories about their hero, Mad Max, who stays behind. Quite inexplicably, Aunt Entity allows Max to live, seemingly out of respect for his audaciousness (promotional materials for the film’s release included stills of Gibson and Turner, in character, posing like a couple of best buds).

Between Bartertown, the children’s grotto, and the high-speed escape in the finale, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome has a lot of ideas—perhaps too many, and some of them incompatible. Each is segmented into a discernable chapter that connects to the rest in the most arbitrary of ways. Moreover, this is a kinder, gentler, pointedly PG-13 rated Mad Max film, with its hero sympathetic to the weak, misunderstood, and innocent, and its villain merciful for no real reason, except to avoid making her too unlikable. Aunt Entity is played by a superstar with a reputation to keep, after all. At the moment Miller cast Tina Turner, the film became unrecoverably Hollywood-ized. She gives a spirited performance, but her effect extends beyond her screen presence. Take the opening credits, during which Turner’s pop song “One of the Living” plays and sets the audience-friendly, pointedly 1980s mainstream mood; her end credits song “We Don’t Need Another Hero (Thunderdome)” topped the charts around the world. Her presence, no matter how submerged in Aunt Entity’s shady dealings, counteracts the series’ sense of desperation and ruthlessness otherwise inherent to Miller’s post-apocalypse.

Between Bartertown, the children’s grotto, and the high-speed escape in the finale, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome has a lot of ideas—perhaps too many, and some of them incompatible. Each is segmented into a discernable chapter that connects to the rest in the most arbitrary of ways. Moreover, this is a kinder, gentler, pointedly PG-13 rated Mad Max film, with its hero sympathetic to the weak, misunderstood, and innocent, and its villain merciful for no real reason, except to avoid making her too unlikable. Aunt Entity is played by a superstar with a reputation to keep, after all. At the moment Miller cast Tina Turner, the film became unrecoverably Hollywood-ized. She gives a spirited performance, but her effect extends beyond her screen presence. Take the opening credits, during which Turner’s pop song “One of the Living” plays and sets the audience-friendly, pointedly 1980s mainstream mood; her end credits song “We Don’t Need Another Hero (Thunderdome)” topped the charts around the world. Her presence, no matter how submerged in Aunt Entity’s shady dealings, counteracts the series’ sense of desperation and ruthlessness otherwise inherent to Miller’s post-apocalypse.

The fast-paced adventures of Indiana Jones and Star Wars had completely dominated Hollywood by 1985, and their influence on Miller is undeniable. At times, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome plays like an escapist Saturday matinee serial, its edge and sense of remorseless fear removed for younger audiences. While Miller explores his individual tonal shifts in his three disparate acts, he uses a visual sense and grandiosity that had become the mainstream—a blockbuster method popularized by Spielberg and George Lucas. However much the element of commercialism in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome does this post-apocalyptic wasteland a disservice, it’s not to any degree that might prevent us from enjoying Miller’s practical stuntwork and technical pleasures. Norma Moriceau’s costumes are as wild as ever, production designer Graham ‘Grace’ Walker erects some impressive sets, and every action sequence feels tangible and real. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome doesn’t have the unrelenting quality or singularity of its predecessors, nor is it cohesive as a whole, but what it offers is well assembled and almost always diverting.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review