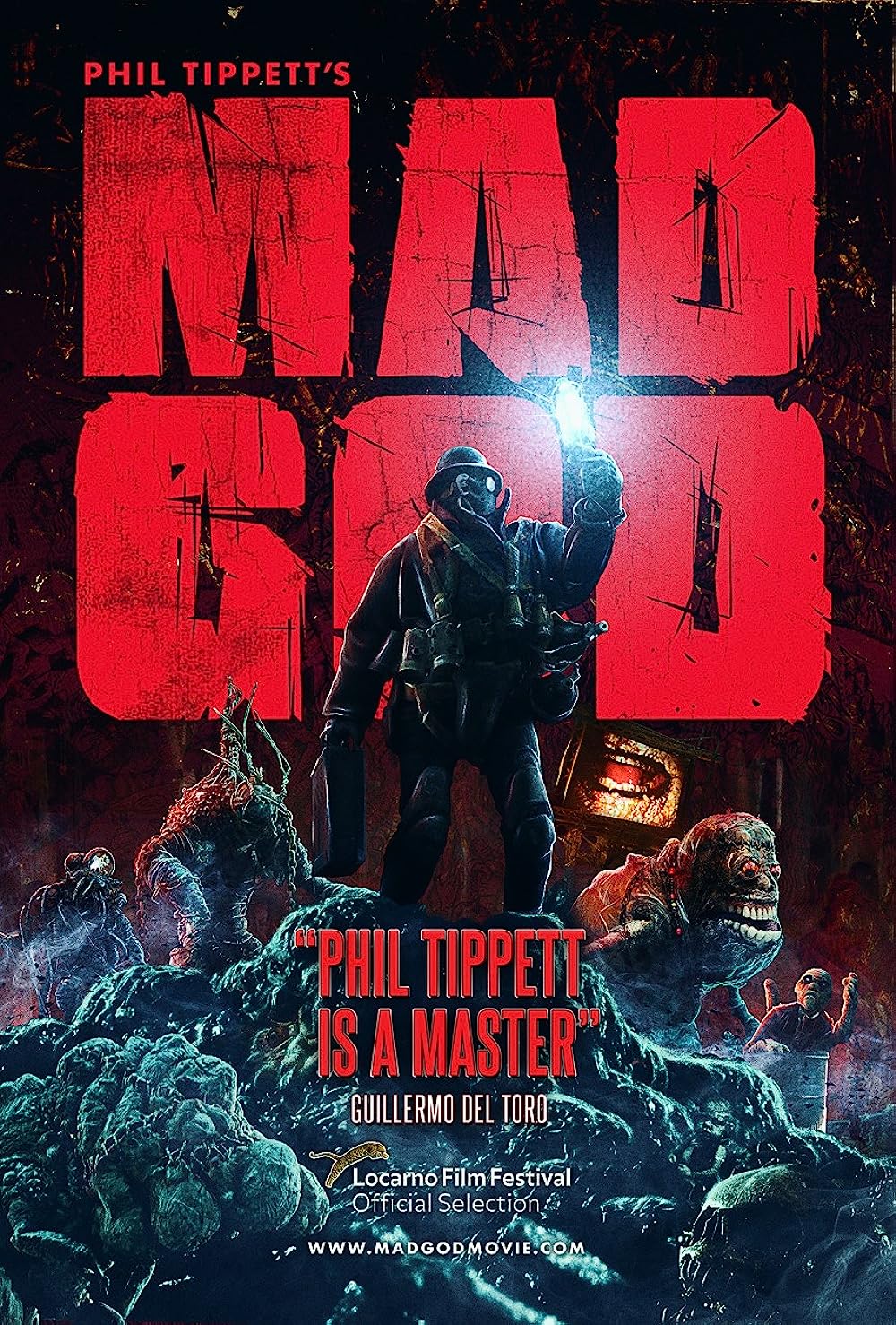

Mad God

By Brian Eggert |

Mad God drills a hole into creator Phil Tippett’s head and looks inside. A renegade work of stop motion and other animation styles, it plays like Tippett visited Hieronymus Bosch’s underworld and returned to tell us about it. The cryptic and symbolic narrative, written and directed by Tippett and following his warped dream logic, unfolds in a series of subterranean worlds, each more horrifying and disjointed than the last. It’s a Dantean odyssey devoid of dialogue and inhabited by fleshy, demented creatures who eke out an existence according to the maniacal social structure that keeps their underworlds operating. But by the end, Tippett shows a transcendent cycle of destruction and rebirth that isn’t a beautiful circle of life but a cruel reality of the universe. Many will come away scratching their heads, wondering what they just watched and why it wasn’t more aligned with standard stop-motion animation fare. But, dark as some Laika productions (ParaNorman, Coraline) can be, they’re kids’ stuff next to this. So children beware. Crafted over three decades and funded partly by a Kickstarter campaign, Mad God forgoes portraying a nightmare and instead mainlines the subconscious’ unrefined nightmare fuel.

If you don’t know Tippett by name, you’ve doubtlessly seen his work. A trailblazer in animation and visual effects, he earned his reputation on Star Wars (1977) and soon became the lead animator for Industrial Light & Magic. His tactile work on The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Return of the Jedi (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1985), and RoboCop (1987) have made him a legend, earning him a bundle of awards, including two Oscars. He also pioneered “go-motion,” a technique that employed computers to create smoother-looking movements than traditional stop motion. But he’s no relic of a bygone era. As founder of Tippett Studios, his team was among the first to adapt to the new demand for computer-generated imagery during the production of Jurassic Park (1993). When Steven Spielberg saw a test sample of CGI, Spielberg hinted that Tippett might be out of a job. “Don’t you mean extinct?” Tippett famously quipped. Both were wrong, as Tippett’s digital animation work on Starship Troopers (1997) and the Twilight saga would prove.

Tippett conceived of Mad God after completing work on RoboCop 2 (1990). He and fellow animators from Tippett Studios began designing characters and building stages; they even shot a few scenes before Spielberg called on Tippett for Jurassic Park. While Tippett supplied designs and animation for several major Hollywood productions in the ensuing years, Mad God’s puppets and sets remained in storage at his company’s Berkeley studio. Some 20 years passed before a younger generation of digital animators found pieces of the abandoned project and convinced their mentor to teach them the old ways. Finally completed during the COVID-19 pandemic with a crew of volunteer artists and craftspeople, Mad God has long been a rumor and dream project that many who follow Tippett’s work never thought they would see. Tippett and his crew suffered through grueling artistic efforts to complete the film, and had the result been anything more conventional, it might have been a disappointment. But Mad God is a visionary, terrifying, imaginative, gory, disgusting, comical, and inspired piece of filmmaking.

Tippett and his crew use a range of filmmaking techniques, including stop motion, digital animation, puppetry, and live-action, to tell a cynical story rooted in a bleak view of the universe. But maybe I’m projecting. According to the press materials, Tippett insists that he created “a narrative the audience members themselves will complete,” drawing from his own dream imagery. Still, he employs a loaded iconography ranging from the Invisible Man to Robbie the Robot to Ray Harryhausen’s Cyclops to biblical references. Indeed, the film opens with a shot of a Babylon-like tower consumed by a dark cloud. Then a scroll quoting Leviticus, the Biblical chapter that finds God at his angriest, unfurls and reminds us that sin will be punished “sevenfold.” According to the verse, humankind’s sin will result in cannibalism, ruined cities, and desolated land. And if Tippett’s film is the visualization of that “sevenfold” outcome, how awful his view of humanity must be. (Not that I disagree with him at this moment.)

Tippett and his crew use a range of filmmaking techniques, including stop motion, digital animation, puppetry, and live-action, to tell a cynical story rooted in a bleak view of the universe. But maybe I’m projecting. According to the press materials, Tippett insists that he created “a narrative the audience members themselves will complete,” drawing from his own dream imagery. Still, he employs a loaded iconography ranging from the Invisible Man to Robbie the Robot to Ray Harryhausen’s Cyclops to biblical references. Indeed, the film opens with a shot of a Babylon-like tower consumed by a dark cloud. Then a scroll quoting Leviticus, the Biblical chapter that finds God at his angriest, unfurls and reminds us that sin will be punished “sevenfold.” According to the verse, humankind’s sin will result in cannibalism, ruined cities, and desolated land. And if Tippett’s film is the visualization of that “sevenfold” outcome, how awful his view of humanity must be. (Not that I disagree with him at this moment.)

Amid a war-torn landscape, a diving bell connected to a cable descends through an underground world, past dinosaur skeletons, past statues of old deities, past the supermassive skull of a titan, and into an apocalyptic sub-level of malformed creatures and pitiless cruelty. When the pod finally reaches the bottom—but far from the lowest point in the journey—an Assassin dressed like a cyberpunk miner finds a world of broken concrete, scattered debris, slime, metal slabs, and pipes in disarray. Following a map that disintegrates a little bit each time he checks his progress, he barely avoids being seen by a potato-headed rancor monster with human teeth before finding a room of animal experiments and a masturbating doll. The Assassin does not stop to help any of the wretched life he sees; he just continues downward, from one cavernous world to the next. One level down, he passes by a grotesque process that suggests an order to the visual chaos: A row of goliaths is electro-shocked into defecating into the mouth of an enormous creature whose uncontained organs represent a bio-network powering a factory that produces disposable shit-slaves.

If there’s a rhyme or reason to their slave labor, they exist to perpetuate a system of tasks ordered by the baby-voiced mouths projected on screens straight out of George Orwell’s 1984 and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). But most of these strawlike shit-people have meaningless deaths—squished by steam rollers, squashed by metallic monoliths, flash burned to a crisp, or stomped out by globulous guards with farting orifices. The film might seem like a meaningless string of horrors until the Assassin, armed with a ticking suitcase, finds himself nabbed and dissected. If he was trying to detonate these forsaken worlds, he fails, only to be disemboweled to access a screaming wormlike creature living inside his gloopy chest cavity. This all might be part of a master plan or repetitive experiment, overseen by a live-action figure credited as “Last Man” and played by Repo Man (1984) director Alex Cox. From the Assassin’s internal worm is the stuff that, when crushed, processed, and refined into a precious material, has the power to destroy and recreate the universe in a punishing and inevitable cycle—and one that evokes Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Terrence Malick’s Voyage if Time (2016) in too close a reference.

At least, that’s what I gathered while absorbing this film, which is impossible to process after a single viewing. Tippett and his crew have rendered an incredible vision over an 83-minute runtime that feels epic and draining. Its displays of cruel underground zones populated by exploitation, endless war, freakish abominations, and ghastly death sometimes feel repetitive. However, each location contains a wealth of nastiness for the eye. If there’s a weak point in the film, it’s the live-action segments featuring Cox, his plastic-looking finger and toenails overgrown, his costume a bit like a Spirit Halloween purchase. But his segment soon passes, leaving us with Tippett’s procession of unspeakable beings. The exception remains a brief segment that looks like a stop-motion Avatar (2009) world of brightly colored, rather cute blobs living in harmony—until their owner, a contorted alchemist, releases a hungry spider-thing to eat one of them. The sight earns a good laugh from the alchemist and downright mouth-agape terror from the viewer.

At least, that’s what I gathered while absorbing this film, which is impossible to process after a single viewing. Tippett and his crew have rendered an incredible vision over an 83-minute runtime that feels epic and draining. Its displays of cruel underground zones populated by exploitation, endless war, freakish abominations, and ghastly death sometimes feel repetitive. However, each location contains a wealth of nastiness for the eye. If there’s a weak point in the film, it’s the live-action segments featuring Cox, his plastic-looking finger and toenails overgrown, his costume a bit like a Spirit Halloween purchase. But his segment soon passes, leaving us with Tippett’s procession of unspeakable beings. The exception remains a brief segment that looks like a stop-motion Avatar (2009) world of brightly colored, rather cute blobs living in harmony—until their owner, a contorted alchemist, releases a hungry spider-thing to eat one of them. The sight earns a good laugh from the alchemist and downright mouth-agape terror from the viewer.

Watching Mad God, you wonder if there’s ever been anything like this. There’s a streak of Rabelaisian imagery running through the film, which cannot help but feel almost funny for its demented ambition. I also thought a lot about William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and his technique of shifting from one character and situation to the next without announcing the switch, actively defying structure. Tippett doesn’t have the randomness of Burroughs, but he does transition from one set-piece to another with an almost cut-in logic. Whole sections of the film could be placed elsewhere with little interruption to the forward momentum. And yet, the narrative does have a progression. What that process signifies may be open to interpretation. Still, the storytelling has an on-the-tip-of-your-tongue coherence that brings to mind David Lynch’s more surreal works, from Eraserhead (1977) to Inland Empire (2006). Then again, Tippett’s brand of surreality makes Eraserhead look like a lighthearted rom-com.

Mad God is a stunning accomplishment and incomparable in its multimedia approach. Although not a profoundly moving experience that uses a narrative to access your emotions, its evocative imagery is primal, curious, and abject, resulting in a sensory overload of imagination and creative power. Tippett’s singular expression feels pure and unfiltered, yet refined by the time-consuming 30-year process of its creation. It’s all the more intriguing that a film as unconventional and downright weird as Mad God comes from one of Hollywood’s greatest artists who has worked alongside box-office giants such as Spielberg, Paul Verhoeven, Joe Dante, and J.J. Abrams to create some of cinema’s most memorable sights. But when unleashed on this personal project, Tippett’s talent produced a dense and wildly inventive film that defies classification. Mad God belongs in a category unto itself, and in today’s glut of marketable and homogenized content, it’s an experimental landmark far removed from anything else you can imagine.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review