Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

By Brian Eggert |

In the early 1980s, playwright August Wilson launched what he called the Pittsburgh Cycle, an ambitious project consisting of ten plays, each meant to encapsulate a different twentieth-century decade of the Black experience in America. Halfway through its completion, Wilson had won two Pulitzers for drama. In the coming years, the Cycle would consume much of his artistic output and life, which ended not long before the Broadway premiere of the final entry in 2005. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the second play written, is set in the oldest period of Wilson’s Cycle and receives a stirring adaptation to the screen by director George C. Wolfe. Given Wolfe’s considerable experience as a stage director (Angels in America; Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk) and filmmaker (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks), he’s perfectly suited to the task. But the power of Wilson’s drama, along with his themes about Black musicians exploited by white producers, seem almost recessive next to the powerhouse performances driving the screen adaptation.

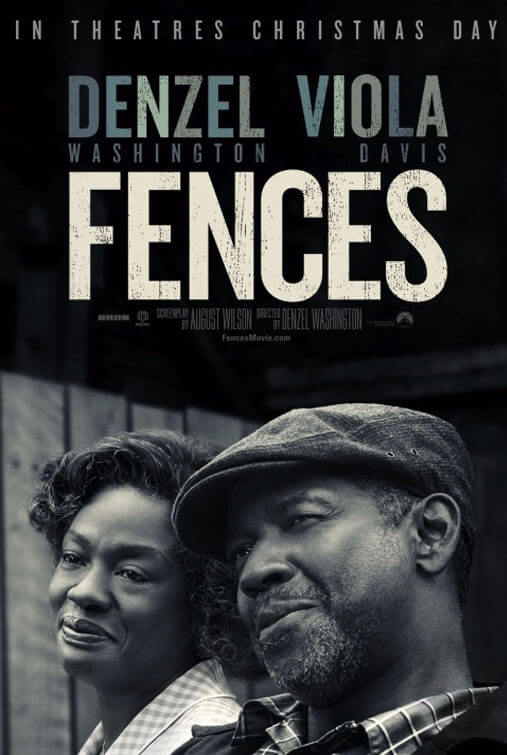

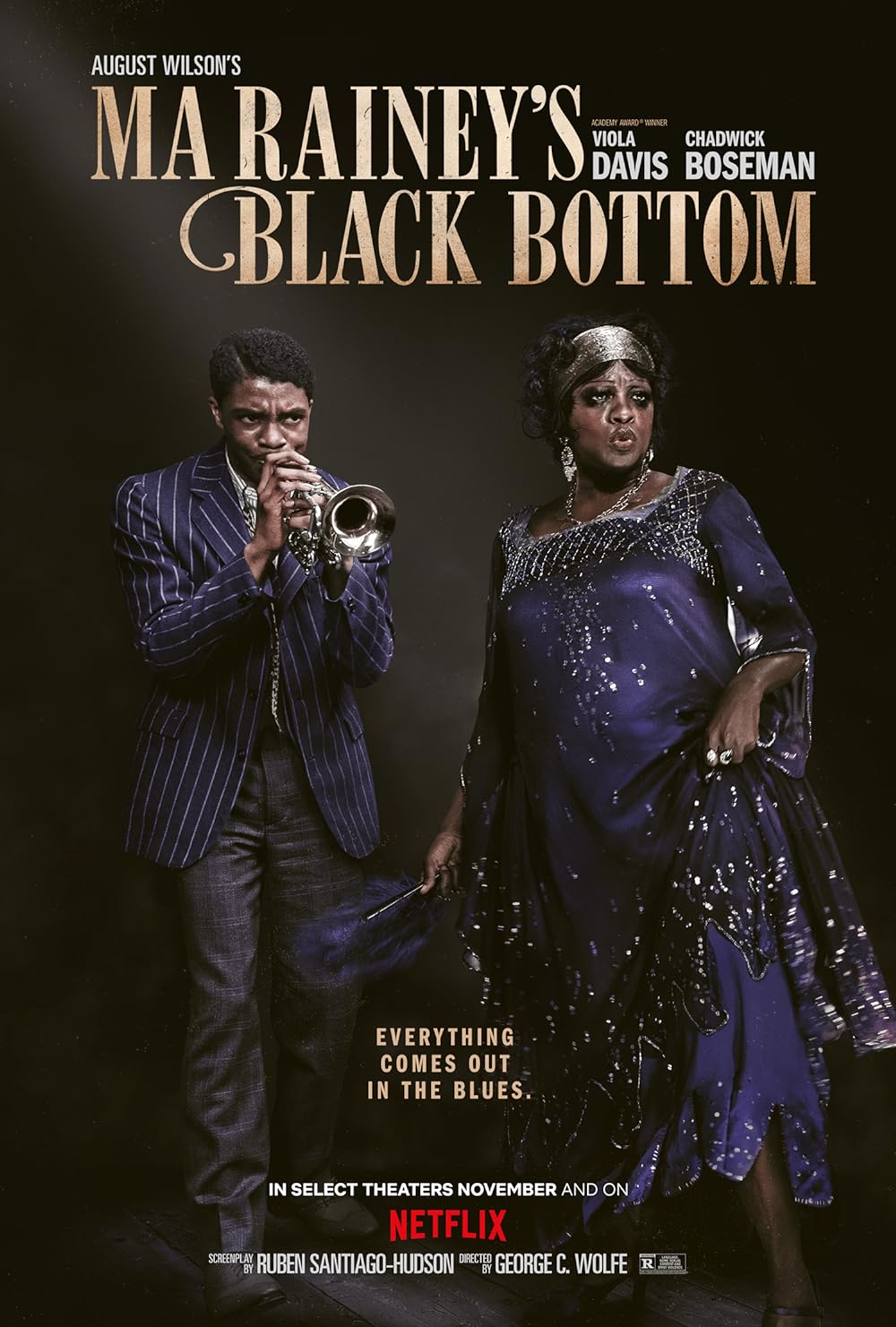

The titular Ma Rainey is played by Viola Davis, who starred in Denzel Washington’s 2016 adaptation of Wilson’s third entry in the Cycle, Fences, and her performance earned an Oscar. It’s hard to imagine that her pairing with Wilson once more won’t result in awards for the actor, who changed her appearance with added weight, a thick application of make-up, and a glaze of perpetual sweat for the role, rendering her almost unrecognizable. If there’s a fault in the performance, it’s that Davis mostly lip-synchs the vocal performance, creating a dissociation between sound and image that rarely translates well to the screen (see Bohemian Rhapsody). Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom also features the final screen performance of Chadwick Boseman, who died tragically in August of colon cancer. As the world remains shocked over the unexpected loss of the cherished Black Panther star, viewers might finally see his full potential realized in a powerful, force-of-energy performance, his second in 2020 after an iconic turn in Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods. Along with a superb supporting cast, Glynn Turman and Colman Domingo above all, the film serves as a showcase for terrific acting.

The film opens in 1927 with a brief prologue not present in the play. Two young African American boys run through the woods. The sound of dogs bark in the distance. We assume the worst—that they’re being chased in advance of some heinous hate crime. But then Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s screenplay reveals the location in the backwoods of Barnesville, Georgia, where members of the Black community gather to hear Ma Rainey, dubbed the “Mother of the Blues,” perform under a tent. Each lyric sounds like a sexualized provocation as Ma Rainey moves her body and arouses the audience into kindled responses. A series of quick transitions bring us to a Chicago recording studio, the location of Wilson’s first scene. Ma Rainey’s band—trombone player Culter (Domingo), pianist Toledo (Turman), and bassist Slow Drag (Michael Potts)—arrive on time. Levee (Boseman), the boisterous trumpet player who plans to start his own jazz band, arrives late, tired of playing this “jug band shit.” On the side, he’s trying to work out a deal with a white producer, Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne), to record his improvisational and escapist songs.

Once Ma Rainey arrives, Davis commands our attention with an I-don’t-give-a-fuck attitude. She knows that she’s talented and that her white manager, Irvin (Jeremy Shamos), needs her. And she knows that she has power in her talent, and she fearlessly uses that to exert herself through a series of demands: an untimely Coca Cola, a recorded introduction by her stuttering nephew (Dusan Brown), and a flaunting of her taboo relationship with a young woman (Taylour Paige). But she doesn’t have delusions of grandeur. “All they want is my voice,” she explains later, demonstrating that she’s know her relationship with the white producer is symbiotic. Although Davis gives a force of Nature performance, full of shouting and prima donna antics, there’s a sadness beneath every gesture that informs her devotion to the blues, a genre that embraces pain. Meanwhile, Levee prefers to forget about his troubles with jazz, which is not to suggest no pain or sadness lingers beneath the surface; it’s just waiting to spill out in a couple of unforgettable scenes.

Once Ma Rainey arrives, Davis commands our attention with an I-don’t-give-a-fuck attitude. She knows that she’s talented and that her white manager, Irvin (Jeremy Shamos), needs her. And she knows that she has power in her talent, and she fearlessly uses that to exert herself through a series of demands: an untimely Coca Cola, a recorded introduction by her stuttering nephew (Dusan Brown), and a flaunting of her taboo relationship with a young woman (Taylour Paige). But she doesn’t have delusions of grandeur. “All they want is my voice,” she explains later, demonstrating that she’s know her relationship with the white producer is symbiotic. Although Davis gives a force of Nature performance, full of shouting and prima donna antics, there’s a sadness beneath every gesture that informs her devotion to the blues, a genre that embraces pain. Meanwhile, Levee prefers to forget about his troubles with jazz, which is not to suggest no pain or sadness lingers beneath the surface; it’s just waiting to spill out in a couple of unforgettable scenes.

Wolfe immerses the viewer in long recording sessions in the studio or basement practice room that unfold with fluid camerawork by Tobias A. Schliessler. And though Wilson seems like the center of gravity, the emotional heights involve Boseman’s performance as a man desperate for Ma Rainey’s ability to carve out her own fate. The climactic scenes of Boseman shouting at God’s unfairness and that “God can kiss my ass” feel even more aching in the wake of the actor’s death. Wilson’s characters often have a challenging complexity that forces an examination of history and power, and the consequences these factors have on people of color. Levee, desperate to prove himself, turns against his fellow musicians when he’s finally rejected by the white producer, leading to a tragic conclusion that simultaneously reveals a range of sensitivity and anger that Boseman has never shown before.

Just as Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom begins with a scene that Wilson did not write, it ends with a scene created for the film—this one more essential than the opening’s addition. The final image of Ma Rainey driving away from the recording studio transitions back inside some time later. A group of white men with instruments, each dull and rigid, sing a passionless version of the song Levee sold Sturdyvant (although “sold” is a loose term in this context). They perform the song like it’s a soap commercial, without any sense of personal pride or ownership over the notes and the feelings they captured for Levee. It’s an apt punctuation of Wilson’s theme about the white appropriation of Black music that would continue for decades from jazz to Elvis Presley. Although these additions, along with the prologue, emphasize Wilson’s themes to the extent of making them unmistakable for an audience not accustomed to theatrical dramatic structure, they nonetheless serve as powerful reminders of the greater historical context.

Producer Denzel Washingon, backed by the Wilson estate, plans to adapt all ten entries in the Pittsburgh Cycle to the screen. If they each end up like Fences and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, audiences have a wealth of layered, intricately written films in their future. Running a brief 94 minutes, Wolfe’s adaptation crackles in its presentation and dramatics, leaving the viewer stunned by the exceptional performances and still-relevant themes. When the film concludes with a spiritless song, it feels like a cruel reminder that Black voices have long been silenced and their work stolen. Fortunately, the score by jazz legend Branford Marsalis dominates much of the soundtrack, and Maxayn Lewis, who performs Ma Rainey’s vocals (aside from an intimate rendition of “Those Dogs of Mine” that Ma Rainey sings to her lover), brings new life to the original songs. From the music to the performances and the people behind them, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom feels like a celebration and mourning for Black artists.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review