Lupin the III: The Castle of Cagliostro

By Brian Eggert |

The character Lupin III was created by manga guru Monkey Punch (the pen name of writer and artist Kazuhiko Kato) in 1967. As one of the most popular figures in anime and manga, Lupin was popularized by a considerable amount of television shows, manga books, feature films, and various other media tie-ins. He was based on French novelist Maurice LeBlanc’s character Arsene Lupin, a lovable scoundrel and thief. Monkey Punch claimed that his Lupin was the grandson of LeBlanc’s original, and the LeBlanc estate has since attempted to assert their claim to the rights of the property time and again, resulting in various thinly disguised attempts to change the name from Lupin to names like Rupan, Wolf (Lupus in Latin), and Vidoq.

By the time Hayao Miyazaki was placed in charge of a Lupin III film in 1979, the franchise was already well-established by a TV series that began in 1971, and a feature film that, titled The Mystery of Mamo, debuted in 1978. Miyazaki had directed several of the television episodes, so he was familiar with the characters, all previously sketched out by the existing material. His task as a burgeoning filmmaker was to place his own signature on the product, titled The Castle of Cagliostro, which would be his first feature film. Armed with a bigger budget than the television show and therefore the ability for a greater scope, Miyazaki was allowed a certain level of creative freedom. Accordingly, the end result varies considerably from the traditional Lupin III schema, in that the character isn’t grossly sex-obsessed and the scenario is more adventurous. In true Miyazaki form, the director tells a story that doesn’t require a particular demographic or invested audience, and aside from some light cursing, it remains appropriate for everyone.

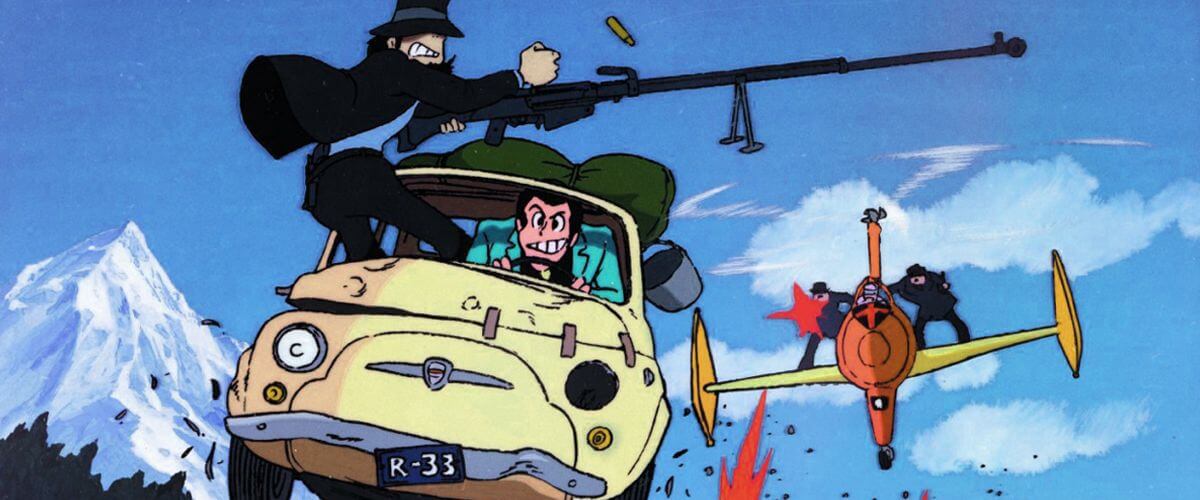

Lupin is an endearing scamp. He’s versed in sarcasm but backs his big mouth with his intelligence, his lean and agile physique, and as a master of disguise, an almost superhuman ability to change his appearance. Despite this, he’s also a cad, a slob, and impulsively carnal. He’s surrounded by his gang of chummy thieves and mercenaries: Daisuke Jigen is a gun-totting marksman, always with a cigarette hanging from his lip and his hat pulled down over his eyes; Goemon Ishikawa is the resident samurai, armed with only his ancient sword; Fujiko Mine is a lusty con woman (and Lupin’s sometimes-lover) who likes to seduce rich men for big paydays. They’re all forever chased by hard-nosed Interpol agent Inspector Zenigata, whose thankless mission it is to capture Lupin.

Miyazaki’s yarn opens with Lupin and Jigen leaving a Monte Carlo casino robbery only to discover that their loot is counterfeit, forged from the legendary presses inside Castle Cagliostro. Lupin resolves to head to the impenetrable castle—which he unsuccessfully tried to burglarize at the beginning of his thieving career—and steal the forgery plates used to make the counterfeit money. On the road to Cagliostro, through an idealized European countryside, Lupin and Jigen are passed in their jalopy by a runaway bride escaping by car from another vehicle of tuxedoed gangsters in pursuit. Ever the good Samaritan when a beautiful woman is involved, Lupin intervenes, saving the bride, named Clarisse. He soon discovers that she’s betrothed to the dreaded Count Cagliostro, who plans to marry her if only to gain access to the castle’s legendary hidden treasure.

As the story unfolds, Lupin must outsmart the Count, as well as survive the perilous obstacles before him in the castle. Fighting metal-reinforced ninja assassins and Schwarzenegger-esque castle guards is enough to bond us to the confident airs of the hero, but there are covert scenes of humor and suspense too. There’s a hilarious underwater break-in sequence where the hero swims against the castle aqueduct’s waterway; barely keeping up with the force of the water, he slowly loses momentum and begins to swim against the current, the realization of his failure evident underwater in his panicked eyes. Or there’s a suspenseful sequence where Lupin prepares to clear the distance between the main castle and Clarisse’s tower via a rope tied to a rocket, but he loses his grip on the rocket and chases it down the roof’s slope; suddenly he cannot stop himself, so he must gain enough speed to just leap the distance by foot.

Through the structure of the story, Miyazaki presents a highly symbolic battle between good and evil, light and dark, day and night. The light is undoubtedly the innocent and virginal Clarisse, whereas the dark is very plainly the Count. Lupin, of course, represents the middle ground between the two as part thief and rogue, part romantic hero. These three elements come crashing together in the climax, where their fates are decided inside the inner workings of the castle’s clock tower. A symbolic setting for these characters if there ever was one, the clock tower recalls Welles’ The Stranger, or even The Lady from Shanghai in its figurative reflectivity of the narrative. The way the plot plays out defines Lupin’s anti-hero status. After all, he begins the tale wanting to rob the castle but then finds himself devoted to saving the Princess. In the end, rather than allowing himself to go completely to the side of light, where he would run away with Clarisse, he leaves her and continues on the road of a criminal on the run from Inspector Zenigata.

In a way, this work most closely resembles Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso, in the sense that both find campy, fun-loving adventure in a romantic, pseudo-European backdrop. Both films rely on classical adventure archetypes about saving the day and getting the girl, and both feature a troubled, confident hero and dastardly villain. There’s an unmistakable charm at work here that supplies either the unfussy viewer or the die-hard Miyazaki fan with plenty to consume. It’s understandable why Steven Spielberg considers this one of his favorite films; Miyazaki’s rendition of Lupin feels like a precursor to the serial-inspired Indiana Jones. Both characters bring adventure, comedy, romance, and suspense closer together than they’ve ever been before. For every dangerous situation that sends us gripping the arm of our chair, there’s another to have us hooting at the hilarity of it all. What’s more, through Miyazaki, the character of Lupin III has never been so likable or universal, enough so that audiences need not be familiar with the character prior to viewing.

The Castle of Cagliostro doesn’t feel like a Hayao Miyazaki film, at least in the sense that it doesn’t embody his archetypal themes. His frequent undercurrents of environmentalism, friendship, and familial bonds have not yet developed, and they wouldn’t emerge in his work until the director’s own manga series and eventual first solo film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. And so, Miyazaki’s first feature resolves to be simply great entertainment, the experimental work of a master testing his own boundaries and possibilities within the animation medium. What he learns in this film about action and suspense he repeats most abundantly in Castle in the Sky and Porco Rosso, films that embrace the director’s personal, auteurist themes alongside escapist scenarios. Without those themes to guide us through the film, Miyazaki makes astonishing use of Lupin III and therein finds his most straightforward exploration of adventure.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review