Loveless

By David Hill |

In an early scene in Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless, there is a heated argument between a married couple, Zhenya (Maryana Spivak, in her first major role) and Boris (Aleksey Rozin, who already featured in Zvyagintsev’s two previous films). They are in the middle of a divorce, and they argue, among other things, about what should happen with their twelve-year-old son, Alyosha (Matvey Novikov). Divorcing couples who fight over their children have been depicted in countless films (most recently in Noah Baumbach’s excellent Marriage Story). However, unlike most married couples in this situation, Zhenya and Boris do not argue about Alyosha because they both want custody, but rather, and shockingly, because none of them wants to look after him once they are divorced. This scene, which ends with a gasp-inducing and unforgettable moment that will not be spoiled in this review, sets the tone for the entire film. Loveless is an incredibly bleak and devastating film whose title could not be more fitting.

After having introduced Zhenya, Boris, and Alyosha, as well as their sad family life in an economical and effective fashion, Loveless takes its time to follow Zhenya’s and Boris’ respective lives. This section of the film, which features two lengthy sex scenes that were inspired by the nude photography of Annie Leibovitz, shows that both have already moved on from their marriage despite not yet being divorced. Zhenya works at a beauty salon and has a passionate relationship with the much older and wealthy Anton (Andris Keyshs). Boris works in a bland corporate office space at an unspecified company and has a relationship with the much younger Masha (Marina Vasileva), who is already quite pregnant with his child. While Zhenya and Boris indulge in their separate lives, Alyosha disappears without a trace. Rather shockingly, Zhenya and Boris only become aware of this through a call from Alyosha’s school the day after he went missing. They each spent the previous night at their respective partners’ place and did not notice Alyosha’s absence.

Most of the second half of Loveless is made up of the search for Alyosha. After the police quickly turn out to be ineffective and unable to help, Zhenya and Boris enlist the help of a volunteer organization that specializes in the search and rescue of missing people. This volunteer organization, recommended to Zhenya and Boris by the police officer in charge of the case, leads the search for Alyosha. In a more conventional film, the boy’s disappearance and the subsequent search for him would be the catalyst for Zhenya and Boris to overcome their differences and to team up together to find their missing son. However, as one should expect from a Zvyagintsev film, Loveless is by no means conventional, and Alyosha’s disappearance only increases the differences and hostilities between his parents.

Most of the second half of Loveless is made up of the search for Alyosha. After the police quickly turn out to be ineffective and unable to help, Zhenya and Boris enlist the help of a volunteer organization that specializes in the search and rescue of missing people. This volunteer organization, recommended to Zhenya and Boris by the police officer in charge of the case, leads the search for Alyosha. In a more conventional film, the boy’s disappearance and the subsequent search for him would be the catalyst for Zhenya and Boris to overcome their differences and to team up together to find their missing son. However, as one should expect from a Zvyagintsev film, Loveless is by no means conventional, and Alyosha’s disappearance only increases the differences and hostilities between his parents.

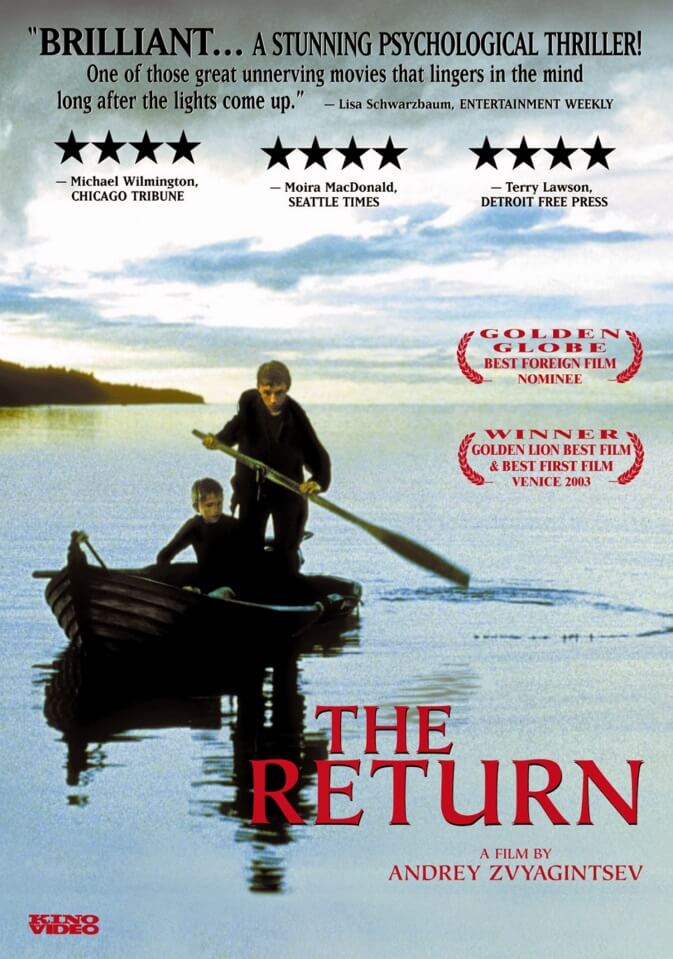

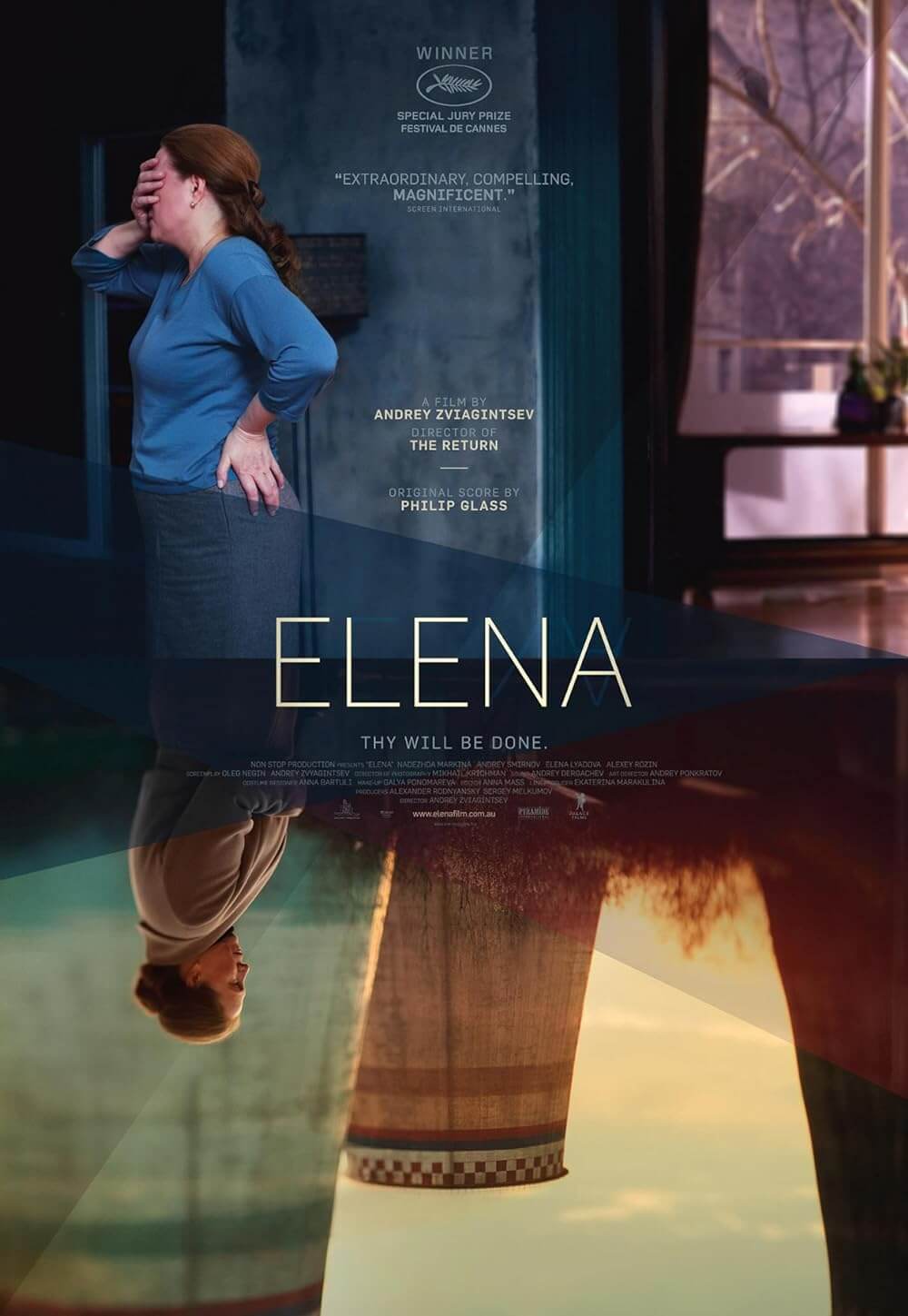

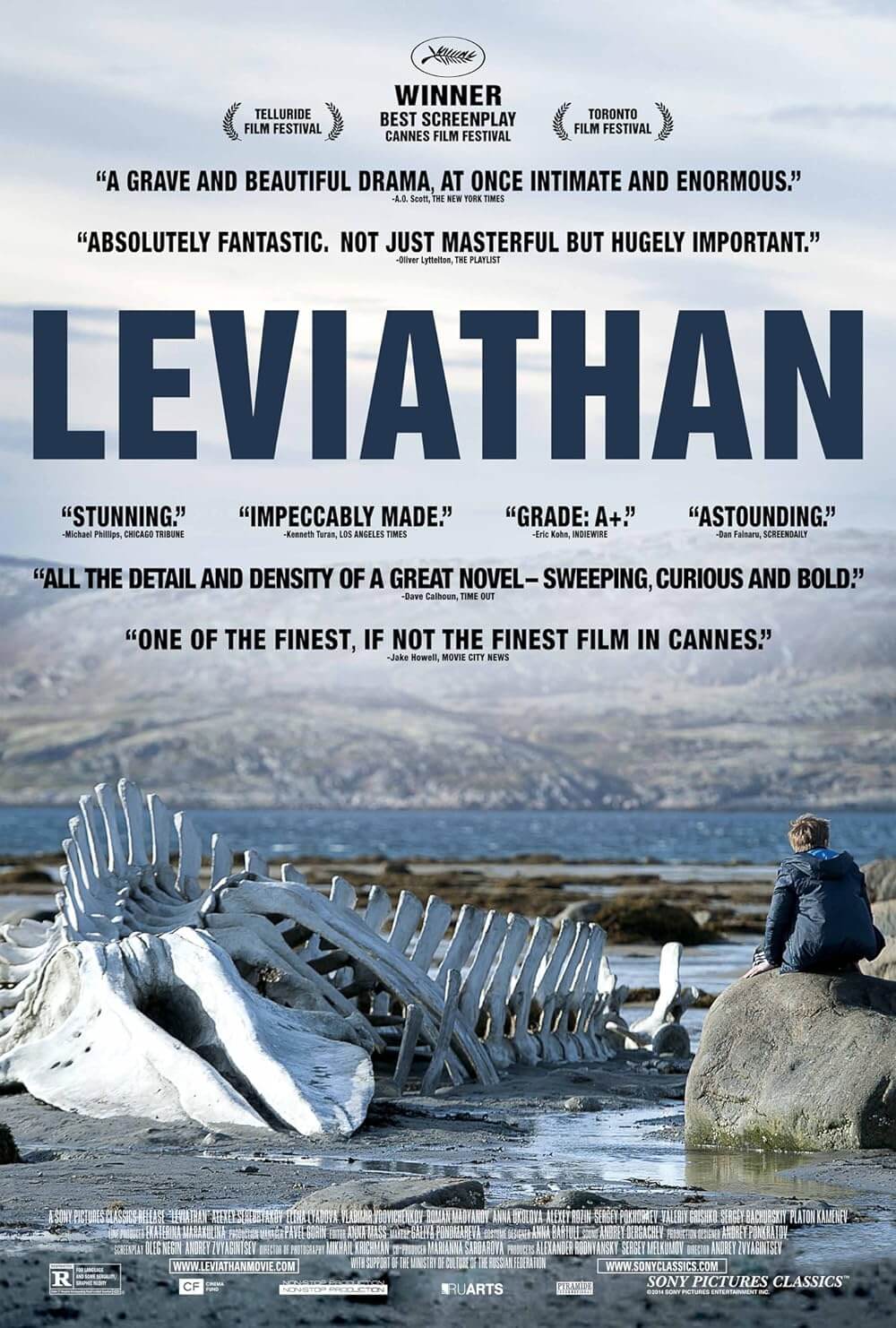

Loveless is Zvyagintsev’s fifth feature and the follow-up to his 2014 masterpiece, Leviathan. The latter was the culmination of the director’s first three films, and it combined the abstract and mythical elements of his first two features, The Return and The Banishment, with the more specific and emotionally engaging elements of his third film, Elena. It was highly acclaimed, but it also caused some controversy in Zvyagintsev’s homeland for allegedly being anti-Russian. Even though it must be said that the controversy was blown up in the Western media, certain Russian officials, in particular Russia’s Minister of Culture at the time, were indeed critical of the film. Zvyagintsev and his producers believed that the controversy surrounding Leviathan was in large part due to the fact that the Russian state had provided 35 percent of the film’s budget, and therefore, they decided not to apply for state funding for Loveless. Instead, they received independent financing from wealthy Russian investor Gleb Fetisov, and the film ended up being an international co-production between Fetisov and investors from France, Belgium, and Germany. It was however exclusively shot in and around Moscow.

With Loveless, Zvyagintsev returned to the more grounded style of Elena. Both films feel more specific and less abstract than Zvyagintsev’s other features, but they still offer much beyond their surface. In the case of Loveless, Zvyagintsev transcends the story of an individual couple to offer poignant commentary on the coldness and emotional detachment in contemporary society. He does so by his usual observational and non-judgmental approach, and by embedding the film’s characters in a fully formed world that feels lived in. Note how he often lingers on secondary characters that do not have any apparent significance for the film’s plot but enrich the fabric of the film. Because of this, Zhenya and Boris do not appear as mere bad apples or even as an exception, but rather they are the unavoidable result of a self-absorbed society that has lost its moral compass. In addition to that, there is a visit to Zhenya’s mother (Natalya Potapova), who Boris calls “Stalin in a skirt” in one of the film’s rare comic moments, during the search for Alyosha. This visit puts Zhenya’s behavior into a new light and makes the viewer question whether there ever was any chance that Zhenya might have turned out differently.

Loveless also deals with the importance contemporary society attaches to outside appearances, and how such appearances often wildly differ from what is actually going on behind closed doors. Both Zhenya and Boris seem to care more about how they appear towards other people than anything else (including their own son), and both are seen spending much time cultivating their appearance. In particular, Boris makes the plan to immediately marry Masha once he is divorced from Zhenya in the hope that his Orthodox Christian employer, who demands that his employees are married and have children, will not notice the divorce. As for Zhenya, we see her getting waxed, getting her hair cut, working out, and posting selfies on social media, and we cannot help but suspect that Anton’s wealth and the possibility of her climbing up the social ladder are the main reasons why she is attracted to him. This theme is further underlined by the fact that the film contains several shots where the camera is looking through reflective glass that prevents the viewer from getting a clear look of what is going on behind it, acting as a barrier between the interior and the exterior.

Another theme of Loveless is the alienating effect of modern technology. Not only does the film depict much selfie-taking and posting on social media, but there is also a notable shot when the search party for Alyosha comes across a huge antenna compound. The workers at the compound tell the search party that they have not seen Alyosha, and the antenna in the background seems to suggest that not even the most powerful technology is able to help us retrieve the genuine human connections that we have lost.

Another theme of Loveless is the alienating effect of modern technology. Not only does the film depict much selfie-taking and posting on social media, but there is also a notable shot when the search party for Alyosha comes across a huge antenna compound. The workers at the compound tell the search party that they have not seen Alyosha, and the antenna in the background seems to suggest that not even the most powerful technology is able to help us retrieve the genuine human connections that we have lost.

According to Zvyagintsev, there were two main inspirations for Loveless. Initially, he wanted to make a film about a married couple who no longer loved each other (he had planned to remake Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, but he could not obtain the necessary rights). Then, he and his regular co-screenwriter Oleg Negin were inspired by a Russian search-and-rescue volunteer organization called Liza Alert. This volunteer group was founded in 2010 after the death of a 5-year-old Russian girl named Liza who went missing and then died in the Russian wilderness due to hypothermia. The organization is often successful, having found a high percentage of missing persons alive. Zvyagintsev has praised Liza Alert in interviews, and he modeled the film’s volunteers after it. Members of Liza Alert even worked as consultants on the production of the film and let Zvyagintsev use their equipment onscreen.

The volunteers depicted in Loveless are indeed a rare source of hope. Even if the viewer does not get to know much about them, it quickly becomes clear that the altruism and professionalism they show during the search for Alyosha stands in stark contrast to the self-absorbed and emotionally detached behavior demonstrated by the other characters. This contrast is emphasized visually as the volunteers wear orange jackets that stand out in the mostly dark cinematography by Zvyagintsev regular Mikhail Krichman, who shot digitally for the first time while working with the director. Another visual contrast is created by the red jacket of Alyosha, who represents the innocence that contemporary society has lost. This reading is supported by the fact that Alyosha, as observed by Catherine Brown, shares his name with the kind and sensitive youngest brother in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel The Brothers Karamazov.

Similar to what happened with Leviathan, some Western critics have interpreted the social commentary of Loveless as a critique of Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Take British film critic Kaleem Aftab who described the film as Zvyagintsev taking aim at life under Putin through the ugliness of divorce. In particular, this interpretation has been based on the film’s epilogue that takes place almost three years after its main events. Among other things, the epilogue depicts characters watching news reports about the war in Ukraine on Russian TV, as well as Zhenya running on a treadmill while wearing a Russia tracksuit. This has led critics to believe that Zvyagintsev wanted to criticize Russia’s role in the war in Ukraine and to equate Zhenya with Mother Russia. Zvyagintsev has however denied having had such intentions, and he said that the sole purpose of the news reports and the Russia tracksuit was to set the epilogue in a specific time–the beginning of 2015, when the war in Ukraine was at a high point, and Russia tracksuits like the one worn by Zhenya were popular following the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

The truth presumably lies somewhere in the middle between the claims that Loveless is a critique of Putin’s Russia and Zvyagintsev’s assertions to the contrary. Regardless of how much one wants to read into the Russia-specific elements of the film, there can however be no doubt that Loveless, like its predecessor Leviathan, contains universal truths about human nature that are not limited to a specific time and place. In particular, the film’s commentary on the self-absorption and emotional detachment in contemporary society, the falseness and artificiality of outside appearances, and the alienating effect of modern technology, applies perfectly to life in the West.

The truth presumably lies somewhere in the middle between the claims that Loveless is a critique of Putin’s Russia and Zvyagintsev’s assertions to the contrary. Regardless of how much one wants to read into the Russia-specific elements of the film, there can however be no doubt that Loveless, like its predecessor Leviathan, contains universal truths about human nature that are not limited to a specific time and place. In particular, the film’s commentary on the self-absorption and emotional detachment in contemporary society, the falseness and artificiality of outside appearances, and the alienating effect of modern technology, applies perfectly to life in the West.

As usual with a Zvyagintsev film, all the technical elements of Loveless are flawless. Apart from the outstanding direction and cinematography, the performances (especially by newcomer Maryana Spivak and child actor Matvey Novikov, who leaves a big impression despite only having a limited amount of screen time), and the score deserve to be highlighted. The score was composed by Russian-born French brothers Evgueni and Sacha Galperine, with whom Zvyagintsev worked together for the first time on Loveless. While their score does not quite have the same impact as the compositions by Philip Glass that Zvyagintsev used in his two previous films, it still adds much to the film’s bleak and tense atmosphere.

However, despite the technical accomplishments and the rich subtext of Loveless, the film’s emotional power stands out the most. Zvyagintsev masterfully creates a feeling of dread and hopelessness that only increases as the film goes along, and that stays with the viewer until long after the credits have rolled. When the search for Alyosha leads Zhenya, Boris, and the volunteers through, among other things, dark woods and abandoned buildings, this feeling becomes so palpable that Loveless could be mistaken for a horror film. Furthermore, there is a late scene at a morgue that is among the most emotional and intense scenes that Zvyagintsev has ever directed. Any potential hope that the main characters will have a better future is dashed for good by the devastating epilogue, which shows that Zhenya and Boris are still as unhappy and frustrated as ever, despite the fact that they are now divorced and that their circumstances have changed significantly.

Unsurprisingly given the quality of the film, Loveless was universally praised by critics, and it won and was nominated for several major awards. Most notably, it won the Jury Prize at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, where it had its world premiere, and it received Academy Award and Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Foreign Language Film. Loveless is indeed a major accomplishment and a highlight in Zvyagintsev’s impressive filmography. It may lack the grandeur and epic scope of Leviathan, but it more than makes up for this with its emotional power and visceral impact. Watching the film is an unforgettable experience that viewers will not be able to shake off easily.

Bibliography:

Aftab, Kaleem. “Loveless: How Russian director is taking aim at life under Putin through the ugliness of divorce.” Independent. 7 February 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/loveless-andrey-zvyagintsev-oscar-leviathan-return-elena-a8199226.html. Accessed 20 October 2020.

Brown, Catherine. “Loveless.” New College of the Humanities. 2 March 2018. https://www.nchlondon.ac.uk/2018/03/02/loveless/. Accessed 20 October 2020.

Choudhury, Bedatri D. “Loveless: Something Else.” Reverse Shot. 16 February 2018. http://www.reverseshot.org/reviews/entry/2423/loveless. Accessed 20 October 2020.

Dobrynin, Sergey. “Andrei Zviagintsev: Loveless.” KinoKultura. October 2017. http://www.kinokultura.com/2017/58r-neliubov.shtml. Accessed 20 October 2020.

Koehler, Robert. “Loveless.” Cinéaste, Vol. 43, No. 3, Summer 2018, pp. 51-53.

David Hill is a lawyer from Switzerland who currently works as a legal counsel for an insurance company. He has long had a passion for cinema, and he uses most of his spare time to watch and research films. His main interest focuses on arthouse films, and he occasionally makes contributions to Deep Focus Review as a guest writer.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review