Longlegs

By Brian Eggert |

A dark fairy tale about an FBI agent tracking a Satanic serial killer, Longlegs is a hollow, weird-for-weird’s-sake thriller written and directed by Osgood Perkins. Heralded by Neon’s effective marketing campaign that has created enough buzz to ensure a hit, the promotional efforts implant more uncertainty and terror than the actual film. It’s an empty, emotionally shallow picture whose style registers as a flatline, muted and unchanging yet decidedly grim. The main draw might be another wild performance from Nicolas Cage, who also produces under his Saturn Films label. And while Cage’s delightfully exaggerated performances often highlight and enrich the material he’s in, others distract. His presence feels anomalous in Longlegs—an interruption rather than a bonding agent between the viewer and the film. A lot of that is happening here, not just from Cage but also in the direction and visualization of most scenes. Combined with a script that lacks humanity or depth, Perkins’ draconian style hangs over Longlegs like a miasma, infecting the narrative and robbing the otherwise inspired premise of life.

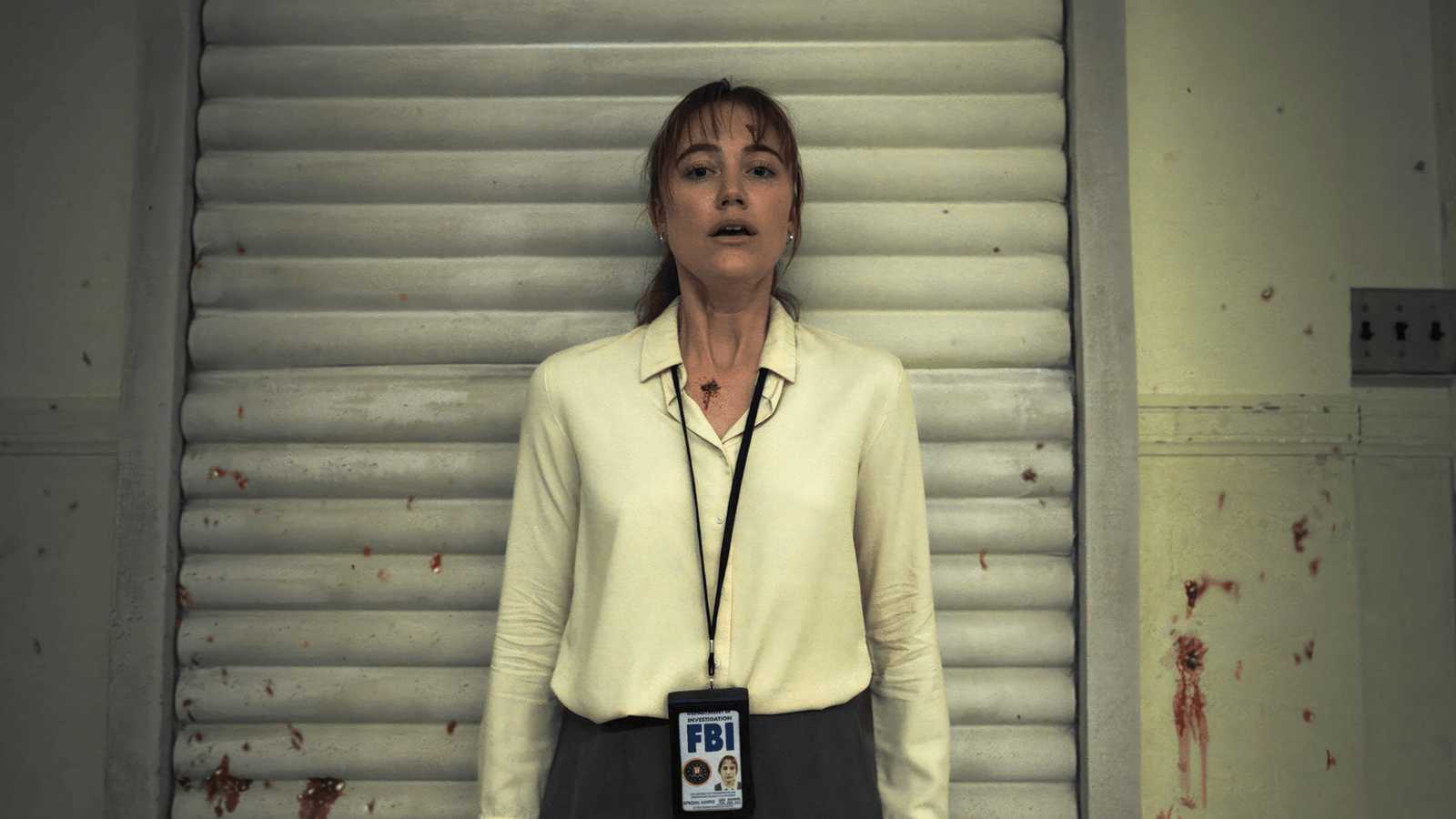

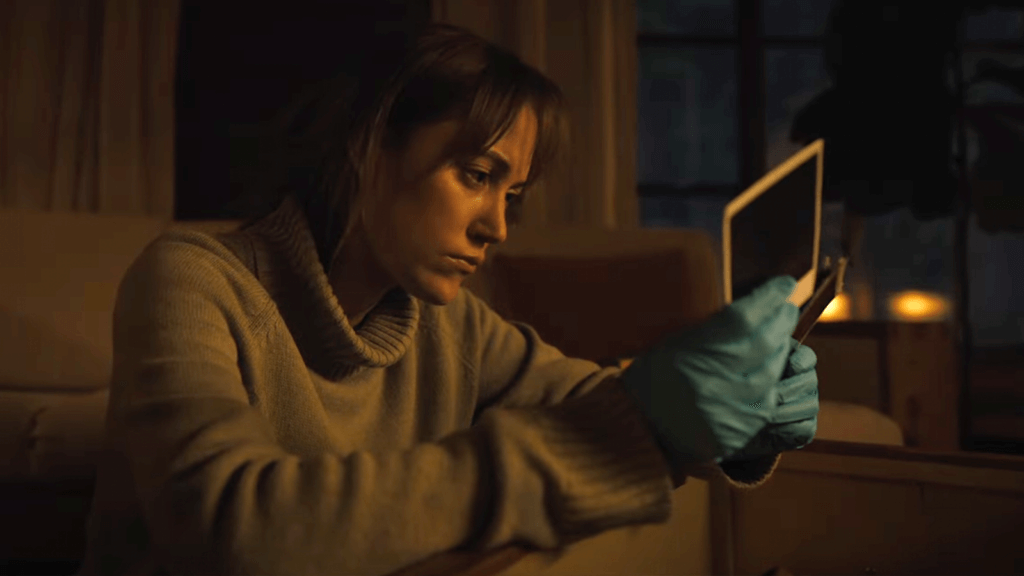

The setup involves the eponymous, obscurely named serial killer who, over several decades, has somehow convinced ten fathers to kill their entire families in grisly murder-suicides—each committed on the calendar day that corresponds to their child’s birthday. It’s unclear how the killer persuades these fathers to commit their crimes, but the FBI has found coded letters at each scene written by the culprit. Enter agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe), a cipher-of-a-character with extra-sensory abilities. Her boss (Blair Underwood, hamming it up) puts her on the case, and, using her “highly intuitive” skills, Harker quickly uncovers Longlegs’ breadcrumb clues and taunting messages. But it’s more than that. She feels a presence nearby, watching her. As she gets closer to her target, she learns how these events connect to her past, signaled by bursting images in her mind and fragmented memories of a bizarre stranger with a mangled face (Cage) who visited her as a child. Perkins and his editors, Greg Ng and Graham Fortin, present the story over three chapters, interrupting the flow with flashes in Harker’s mind of snakes and drains, evoking Psycho (1960), the film that made Perkins’ father an icon.

From the outset, Perkins calls attention to his mannerist stylistic choices. For a while, I hoped the style might lead to some revelation tied to the narrative, producing a form-follows-function master plan. But his film’s conspicuous audio and visual design amounts to a forced and abrasive aesthetic. Note how the first scenes and, later, flashbacks and memories—any scenes set in the past, really—manifest in a vintage 8mm format, complete with a boxy shape, rounded corners, and a grainy appearance. Transitions from these sequences to the present, sometime in the 1990s, extend the frame’s borders outward into a widescreen rectangle, calling attention to the switch. Elsewhere, Andrés Arochi’s cinematography adopts a Kubrickian sensibility, with symmetrical compositions and figures centered in the wide-angled frame. Every angle looks so arch that the film’s general ostentatiousness makes any genuinely eerie moment feel like more of the same instead of a standout shocker.

Longlegs is a meticulously constructed film, like a diorama conceived and built by a fastidious serial killer. Doubtless, that’s the point. But rather than genuine scares, Perkins constructs an entire film operating on the same uncanny level, making no scene more unnerving than the last. Instead of overwhelming the viewer in the same manner as, say, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), an evident influence here on multiple levels, it left me at a distance. Besides a few gnarly sights and some disturbing violence, the closest Longlegs comes to producing a reaction is when the histrionic score, credited to the mysterious Zilgi, bursts onto the scene, prompting an unavoidable jolt. But it’s less an emotional response than a reflex, like someone popping a balloon next to your ear. Worse, the story is predictable. The climactic scene involves something the viewer dreads after learning early on that Harker’s boss has a child with a birthday coming up.

Longlegs is a meticulously constructed film, like a diorama conceived and built by a fastidious serial killer. Doubtless, that’s the point. But rather than genuine scares, Perkins constructs an entire film operating on the same uncanny level, making no scene more unnerving than the last. Instead of overwhelming the viewer in the same manner as, say, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), an evident influence here on multiple levels, it left me at a distance. Besides a few gnarly sights and some disturbing violence, the closest Longlegs comes to producing a reaction is when the histrionic score, credited to the mysterious Zilgi, bursts onto the scene, prompting an unavoidable jolt. But it’s less an emotional response than a reflex, like someone popping a balloon next to your ear. Worse, the story is predictable. The climactic scene involves something the viewer dreads after learning early on that Harker’s boss has a child with a birthday coming up.

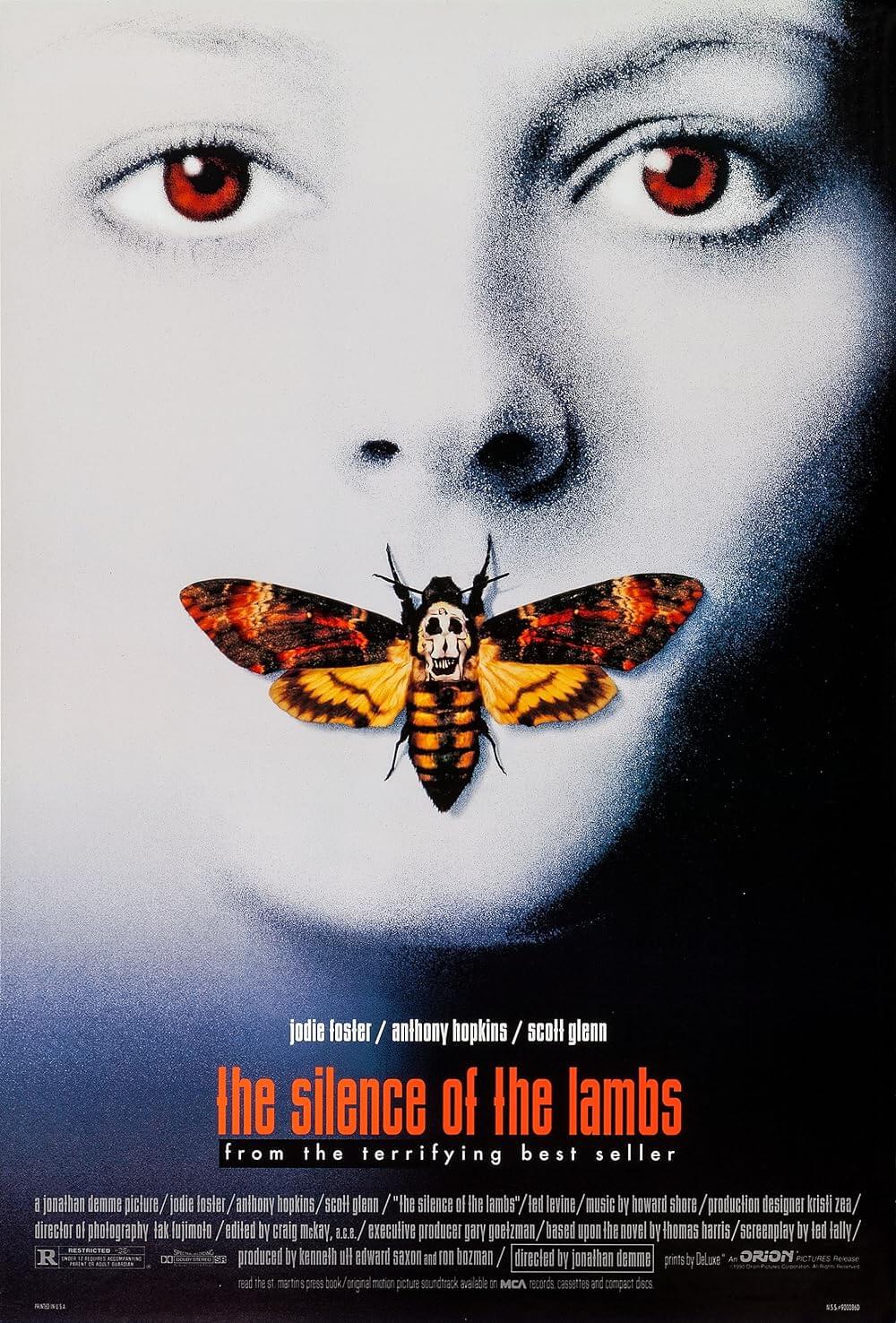

Obvious comparisons can and should be made to The Silence of the Lambs (1991), but the similarities are superficial and only underscore what’s wrong with Longlegs. Jonathan Demme understood that the humanity of his characters, from Clarice Starling to Jack Crawford, stood in the face of the inhumanity evidenced in Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter. Perkins gives Harker no dimension, and apart from Monroe’s ability to evoke terror, she seems doll-like and unreal. Not even her calls home to her religious mother (Alicia Witt, stilted) contain more than a hint of a backstory. Once again, this is surely intentional, given what Perkins reveals in the third act, but it does nothing to connect the viewer with the material. Hell, even Kubrick, whose films are often described as cold or detached, managed to imbue humanity into his uncanny horror epic, The Shining. Perkins forgoes emotional connections and lasting dramatic impact for his puzzle-box construction, which is more neat and passively appreciable than involving.

Perkins designed the film’s disorienting and claustrophobic situations to unsettle the viewer, making his audience feel trapped and suffocated; he holds our heads under the overbearingly abnormal surface, where we gasp for air. Perkins effectively creates a sensation that some unknown presence lingers in the room, hiding just out of sight. But it’s difficult to care when the characters are so ornate and the performances are so affected. A gaunt Monroe presents an unlikely candidate for the FBI in her edgy, wary-eyed instability, suggesting she should have been a psychic consultant instead of an agent. And whenever the killer arrives onscreen, Cage doesn’t disappear into his performance, despite some freaky prosthetics that make him look like a celebrity who’s undergone too much lousy plastic surgery. Under his character’s silver hair, pale skin, and white getup, Cage gives a characteristic performance, wonderfully over-the-top and theatrical in a Kabuki kind of way. It’s an admirably peculiar turn, marked by Cage’s usual screaming and unorthodox line delivery. He’s entertainingly odd, but he’s not a character, more of a thing, and far too recognizable as the actor beneath his character’s mask for Longlegs to make an impression.

I cannot deny that Perkins has fashioned an intentional piece of work, with every piece exactly where he wanted it, like an orderly nightmare. But similar to his previous films—The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House (2016), and Gretel & Hansel (2020)—I didn’t feel much of anything while watching Longlegs. The basic story intrigues, but Perkins’ presentation does more to distract from the narrative with its showy weirdness than immerse us in the experience. The filmmaker’s preoccupation with motifs such as dolls, occultist imagery, bible verses, and bedtime stories certainly bears investigation and deciphering, I suppose, but the thought put into his film erects only an impressive façade. Behind it, the buttresses will snap and break under scrutiny, leaving its admittedly creepy artifice to collapse onto its slight characters and overly familiar plot.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review