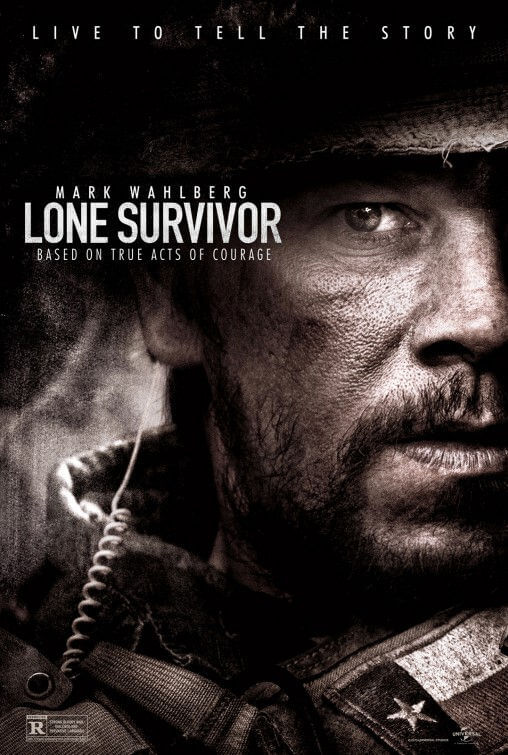

Lone Survivor

By Brian Eggert |

Jingoist and bordering on propaganda, Lone Survivor is a war film uninterested in directly addressing the politics of war; instead, it’s concerned about the camaraderie of soldiers and the extreme physical toils they put themselves through to train and thrive on to maintain their team—very much akin to Act of Valor, the 2012 actioner starring active U.S. Navy SEALs. Based on Marcus Luttrell’s best-selling nonfiction book, the film follows Navy SEAL Team 10 on their March 2005 mission Operation Red Wings, in which Luttrell’s four-man reconnaissance team went into Afghanistan to scout Taliban leader Ahmad Shahd. And while the title and author give away what happens to whom, it’s more of a battle film akin to Black Hawk Down, about the brotherhood of the SEALs and their never-stop-fighting attitude. There’s no discussion or skepticism toward politics or the reasons for war because, well, theirs is not to wonder why; theirs is but to endure endless punishment to preserve the team.

“The team,” in this case, is their immediate SEAL unit, and by extension, their country, which orders them “into those cold, dark corners where the bad things live, where the bad things fight. We wanted that fight at the highest volume.” Luttrell’s patriotic appreciation of battle and Navy SEAL solidarity is narrated by Mark Wahlberg, who plays Luttrell here. Along with his gung-ho compatriots—Axe Axelson (Ben Foster), Danny Dietz (Emile Hirsch), and Mike Murphy (Taylor Kitsch)—Luttrell takes position in the Hindu Kush mountains of the Kunar province to overlook Shahd’s compound. While scouting, they’re approached by an elderly man and two adolescents in the woods, but there’s no certainty if these civilians are Taliban-sympathetic. What to do, what to do? The SEALs have three options: “terminate the compromise”, take them captive, or release them and risk them alerting the compound below.

After some debate, they resolve the decent thing to do (as mandated by the Geneva Convention) is release the three—an ill-fated choice, given what follows. The freed herders quickly alert the base below and before long, the four SEALs are pinned down by a throng of encroaching Taliban, fighting for their lives. It’s a 30-minute sequence of unceremonious gunfire and death, interrupted by the usual everything-goes-wrong situations customary to war movies. Their satellite communications prove unreliable, their air support is delayed, the top brass are moving too slow, and the rescue choppers deployed are quickly shot down by the enemy. When it was all over, more than a dozen American soldiers died in a mission that was at first deemed to be not particularly dangerous. But don’t go searching these events for a critique about why the U.S. military is in the Middle East. See Lions for Lambs, In the Valley of Elah, or Redacted for that.

Director Peter Berg, who also wrote the screenplay, doesn’t use Luttrell’s story as a springboard to discuss the insanity of war, the politics that led the U.S. into Afghanistan, or the failure of U.S. forces to sufficiently strategize an operation with “a lot of moving parts” before executing it. Instead, Berg uses every technical trick in his arsenal to make the film a visceral experience, including shaky cams and sharp cutting to realize the intense action. The editing is particularly effective in a sequence where Luttrell and his team leap from a rocky ledge and tumble down a hill on which they collide with jagged rocks and trees, leaving them bloodied and broken. Berg’s cinematic realization of these events is exciting, but his angle lacks substance. The characters have thin personalities that feel all but issued to them by their drill instructors (as seen in the actual SEAL training footage during the opening credits); these aren’t individuals with distinct character traits, and they’re best differentiated by naming the actors playing them.

Lone Survivor has been something of a passion project for Berg, who’s better when exploring real-life wartime situations (see The Kingdom) than his infrequent sci-fi-infused efforts (don’t see Hancock). To adapt Luttrell’s book, Universal Studios asked Berg to direct Battleship first, a bargain he agreed to and, no matter how effective (or successful) Lone Survivor might be, lost. His film is a noble testament to men who died in Operation Red Wings, a straightforward Navy SEAL celebration through the retelling of their story. But then it’s capped by the misplaced use of Peter Gabriel’s cover of “Heroes” by David Bowie over the end credits. To paraphrase World War II vet and filmmaker Samuel Fuller (The Big Red One), “There are no heroes in war, only survivors.” Lone Survivor’s major saving grace is that it never resorts to actual flag-waving, but enough pro-military overtones subsist in the material to consider it an effective recruiting video.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review