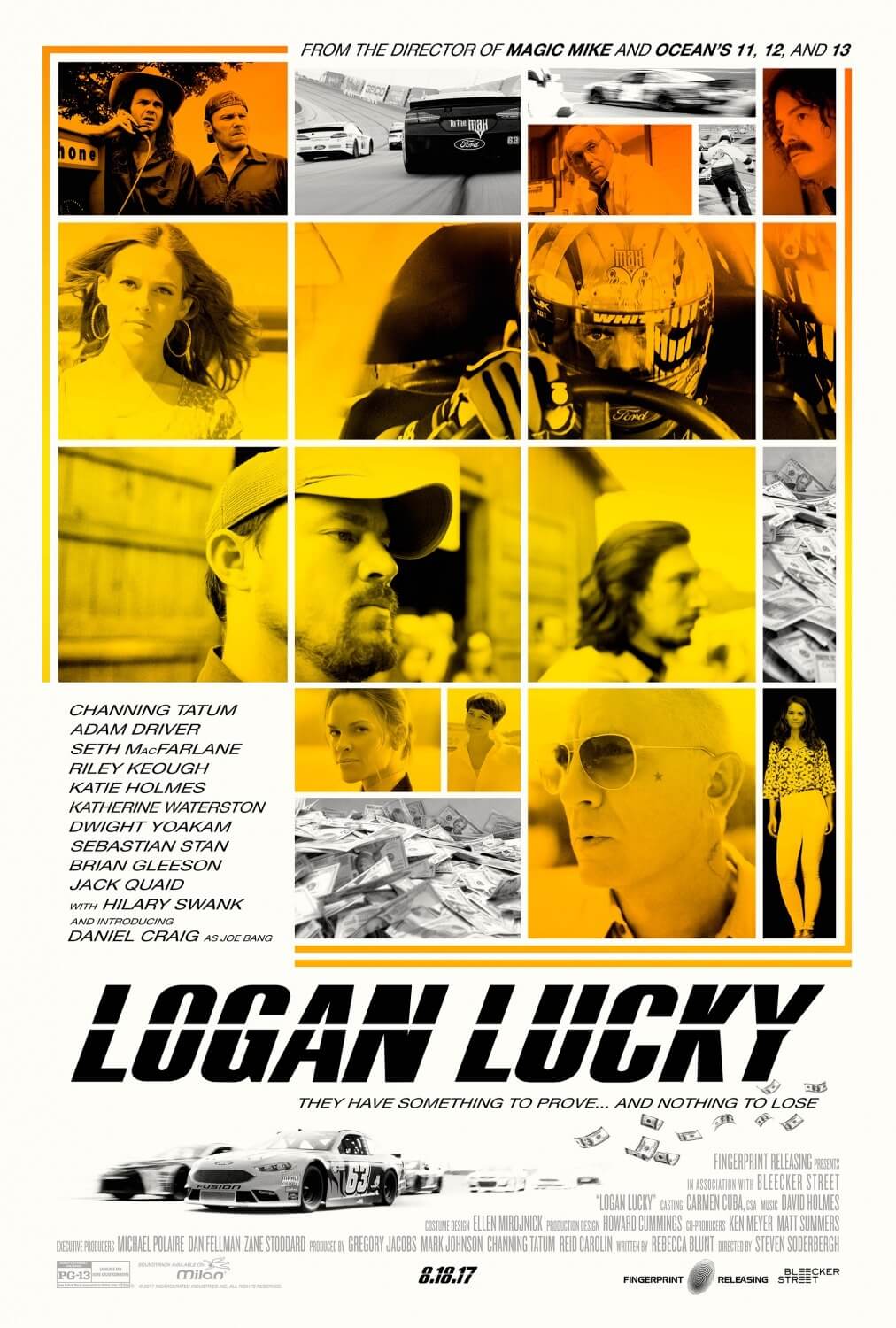

Logan Lucky

By Brian Eggert |

Four years after announcing his retirement with a final film (Side Effects, 2013), director Steven Soderbergh returns from his thankfully short-lived reprieve from filmmaking with Logan Lucky. A familiar sort of heist comedy for Soderbergh, the film shares much in common with his Ocean’s trilogy and Out of Sight (1998), except it’s dressed down in “redneck” garb that distinguishes its characters, central robbery, and personality. (The film even describes itself as “Ocean’s 7-11,” preemptively making the comparison before its audience does.) And though its summer release and star-studded cast suggest a blockbuster quality, Soderbergh’s restrained, understated, yet fastidious technique distinguishes his approach from other filmmakers more prone to showboating. Sweeping stories from his two-part Che (2008) to the globe-trotting epidemic thriller Contagion (2011) feel intimate and human in his hands, whereas his seemingly absurd tale of male strippers in Magic Mike (2012) is elevated by his discerning approach. All of this is to say that Logan Lucky has been given Soderbergh’s dependable, accessible, but also perceptive touch.

Once again, Soderbergh takes on multiple roles behind the camera, hiding behind his worst-kept-secret pseudonyms. His alias “Peter Andrews” handles cinematographer duties, while he serves as the editor under “Mary Ann Bernard.” Logan Lucky‘s screenwriter named “Rebecca Blunt” marks another pseudonym, although insiders remain unsure if Blunt is really Soderbergh or his wife, Jules Asner (who actually exists). Soderbergh’s apparent need to control every aspect of his production—including the digital photography’s color saturations and deliberate movements, leisurely pacing, and narrative material of his film—seems to explain why he often chooses stories about elaborately staged robberies or schemes. The crimes in his films involve meticulous planning and systematic follow-through, the details of which are sometimes not always shared with the audience. Nevertheless, we cannot help but suspect Soderbergh has applied his exacting, if somewhat cold approach to figuring out every element of the heist, and then presenting it to his audience in a precise way.

In any case, the script contains the director’s dry wit and penchant for deadpan hijinks, yet it never winks at the audience or dispels its own conceit, much like Ocean’s Eleven (not its self-aware sequels, however). But rather than the glitzy excess of Las Vegas and suave celebrities that surround George Clooney’s Danny Ocean, this film adopts a hilarious amount of Southern-fried glut: NASCAR equated to heaven on Earth, dreadful child beauty pageants, garbage scrounging, and homemade bombs saturate the white trash milieu. After getting sacked from his construction job filling sinkholes underneath the Charlotte Motor Speedway in North Carolina, Jimmy Logan (Channing Tatum) takes stock of his life. His young daughter, Sadie (Farrah Mackenzie), looks up to him, but she lives with his ex-wife Bobbie Jo Chapman (Katie Holmes) and her successful car dealer husband Moody (David Denman). His no-nonsense sister Mellie (Riley Keough) is a hairdresser, while his brother Clyde (Adam Driver), who tends bar at the “Duct Tape Bar & Grill” and lost a hand in Iraq, insists that their family has a curse. Jimmy wants to change that.

All at once, Jimmy concocts a plan for a Big Score: they’ll rob the forthcoming Coca-Cola 600 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway by tapping into the pneumatic tube system that carries cash from the registers to a safeguarded vault. But he needs more than two Logans to carry out the plan; he also needs three Bangs. Specifically, he needs Joe Bang (Daniel Craig), a convicted safecracker and explosives expert. But Joe has five months left on his prison stretch, and so Jimmy and Clyde must get Joe out of prison for a few hours and return him without anyone knowing—a scheme that proves how tricky this film can get. (Dwight Yoakam has a wonderful bit role as the prison’s Warden Burns.) For added help on the robbery, Jimmy enlists Joe’s yokel brothers Sam (Brian Gleeson) and Fish (Jack Quaid). And while the film might seem as though it pokes fun at its characters’ silly accents and twang, Soderbergh offers surprisingly touching moments between Jimmy and Sadie, and their bond through John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads.” Similarly, though Clyde behaves like an internal weirdo who doesn’t talk much, Driver gives the character an unspoken nobility and sadness.

All at once, Jimmy concocts a plan for a Big Score: they’ll rob the forthcoming Coca-Cola 600 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway by tapping into the pneumatic tube system that carries cash from the registers to a safeguarded vault. But he needs more than two Logans to carry out the plan; he also needs three Bangs. Specifically, he needs Joe Bang (Daniel Craig), a convicted safecracker and explosives expert. But Joe has five months left on his prison stretch, and so Jimmy and Clyde must get Joe out of prison for a few hours and return him without anyone knowing—a scheme that proves how tricky this film can get. (Dwight Yoakam has a wonderful bit role as the prison’s Warden Burns.) For added help on the robbery, Jimmy enlists Joe’s yokel brothers Sam (Brian Gleeson) and Fish (Jack Quaid). And while the film might seem as though it pokes fun at its characters’ silly accents and twang, Soderbergh offers surprisingly touching moments between Jimmy and Sadie, and their bond through John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads.” Similarly, though Clyde behaves like an internal weirdo who doesn’t talk much, Driver gives the character an unspoken nobility and sadness.

Given the film’s setting in blue-collar towns across North Carolina and Virginia (but shot mostly in Georgia), and given the prevalence of such Southern locales in the headlines today, it’s difficult not to look for embedded parallels or commentary. Perhaps it’s reaching to suggest Soderbergh’s film associates the Coca-Cola sponsored NASCAR race with Donald Trump: a massive, wealth and status-obsessed entity that nonetheless commands the faithful devotion from crowds of followers unaware, or at least unconcerned, that their allegiance was won by a money-grubbing monster affecting a false down-home sensibility. Certainly, Soderbergh depicts issues of class as the broken coal mining families lovingly attend the race, the institution that charges $10 for a glass of cheap beer. His film identifies with its white trash heroes; meanwhile, it mocks the well-to-do characters as entitled and superficial morons. Take Seth MacFarlane as an ego-maniacal energy drink guru named Max Chilblain, who sponsors a NASCAR driver and tells everyone that he runs a billion-dollar company. Just as eccentric and absurd, driver Dayton White (Sebastian Stan) refers to his body as an “OS” and food as “software,” the kind of lifestyle metaphor conceived only by the rich and famous.

Logan Lucky has all the effortlessness one would expect from its director, though Soderbergh keeps the proceedings airy and playful, while the audiences tries (and fails) to keep up with the fun central scheme. But it’s not the kind of film that you can guess your way through; you just have to watch, engaged with wonder as the master plan unfolds. Moreover, Soderbergh proves once more that he can somehow draw the best out of Tatum; this is true of Craig’s uncharacteristic comic performance as well. The current James Bond demonstrates he’s capable of humor by getting a number of the film’s best laughs, including a bit where he explains “science” to his fellow thieves. (Here’s hoping we see more of Craig’s lighter side.) The self-assured filmmaker has returned in full form with Logan Lucky, delivering a cinematic gift of technical brilliance, subtle work with actors, and slick plotting. And while his temporary retirement was as much time as some other filmmakers take between films, his prolific career made his absence seem achingly long. With an entertaining and slyly germane work, Soderbergh reminds us why he remains one of today’s most compelling, skilled, and entertaining filmmakers.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review