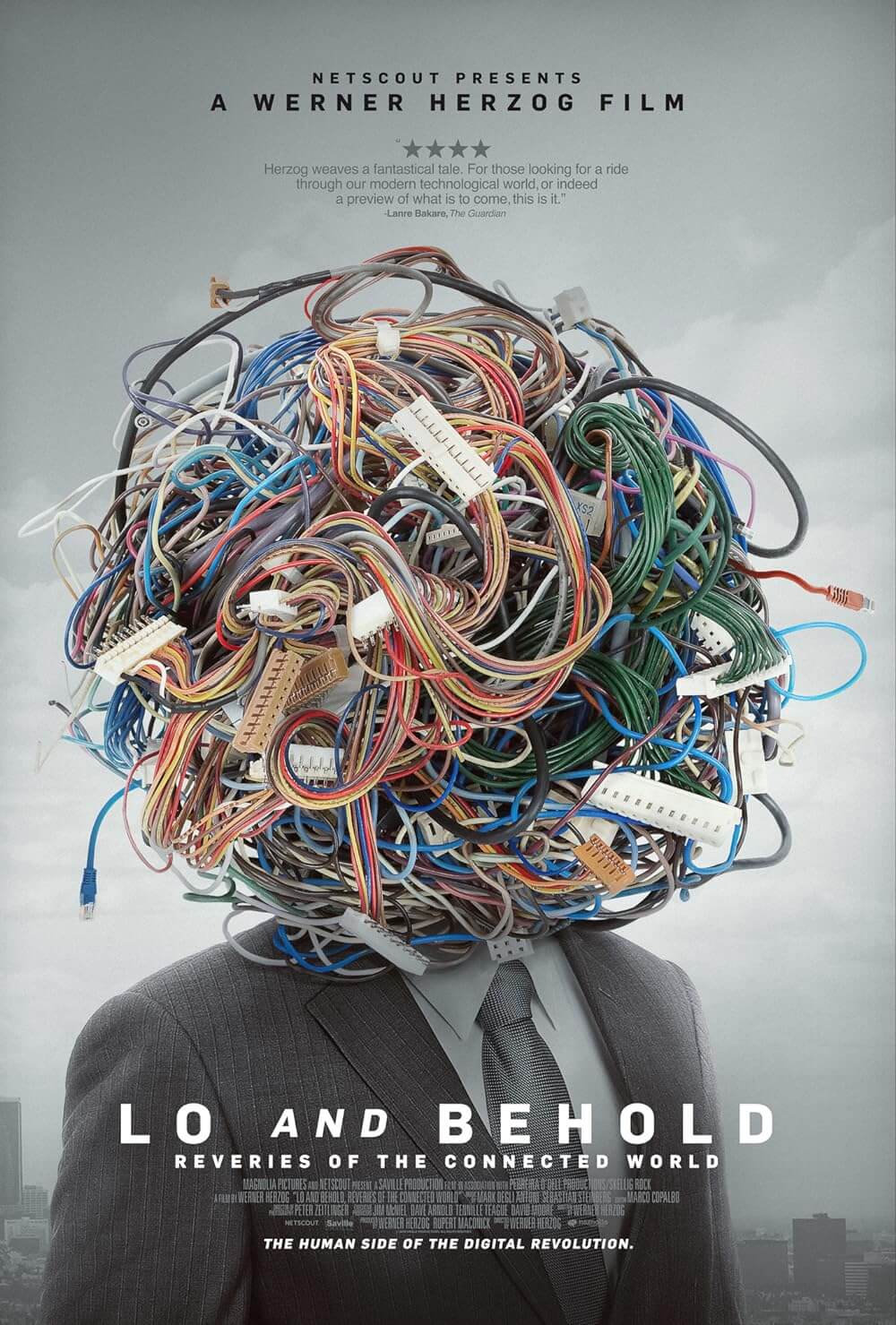

Lo and Behold, Reveries of a Connected World

By Brian Eggert |

With his cameras somewhere in the depths of the UCLA campus, filmmaker Werner Herzog calls the underground corridors “repulsive”—and indeed they are, given their yellow-green vomit color. He soon finds computer scientist Leonard Kleinrock, one of the pioneers who launched the internet. Kleinrock leads Herzog’s probing camera into a room he describes as “sacred” and “holy”, heading into a virtually empty room, save for a rectangular box that looks like an early refrigerator. This host machine is where the internet began. Kleinrock shares an anecdote about the first internet communication in 1969 from UCLA to Stanford. A tech in California intended to type “login” but only got as far as “lo” before the system crashed. Kleinrock smiles proudly and labels the moment “prophetic,” since “lo” means to bring a sense of awe or wonderment. Herzog borrows from this story for the title of his documentary, Lo and Behold, Reveries of a Connected World.

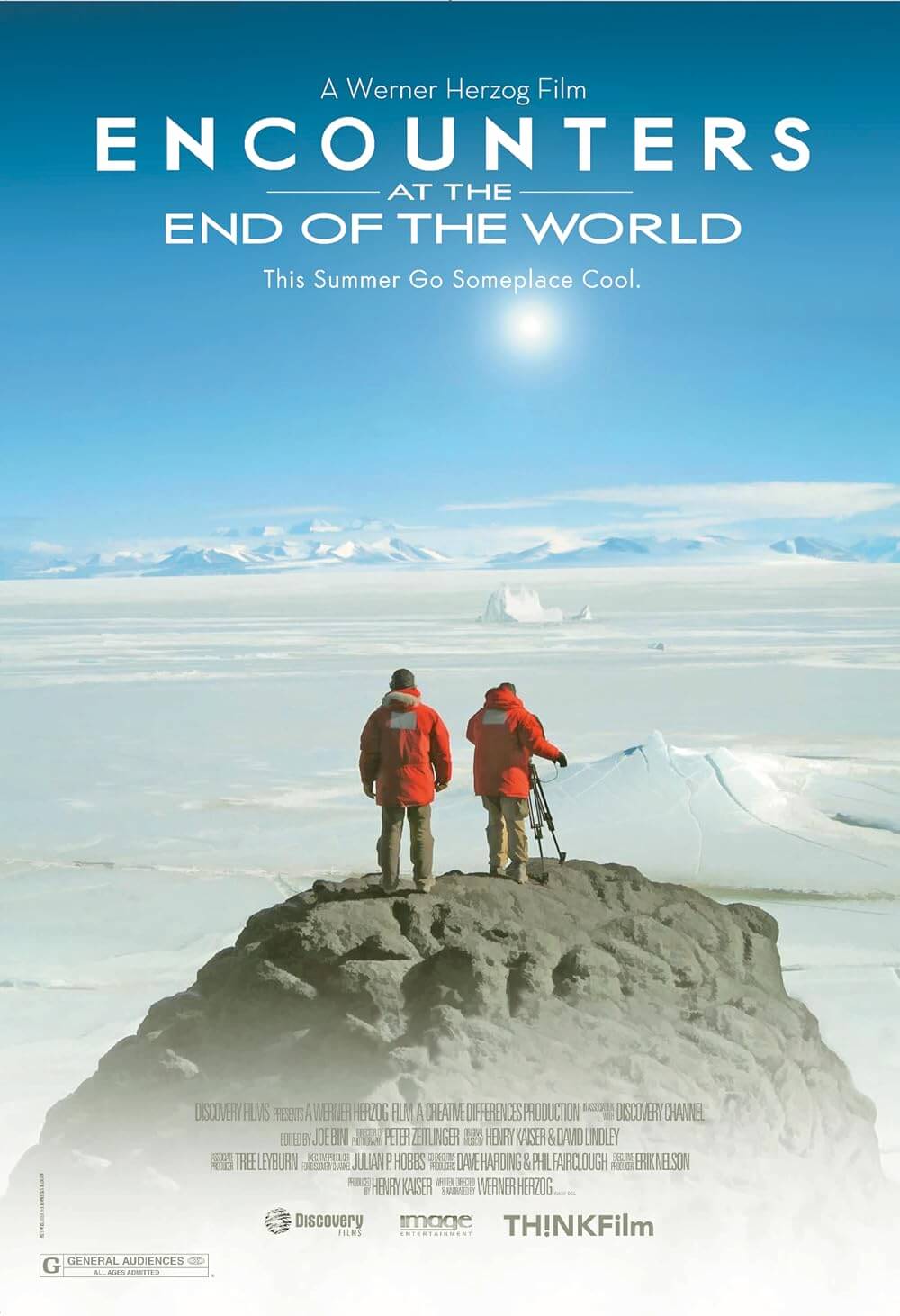

Herzog’s film would make a fine first half of a double feature right alongside Alex Gibney’s doc Zero Days, released earlier this year. Both pictures seem fascinated and terrified by the possibilities of technology, communication, and wildly out-of-control trends on the internet. While Gibney’s film delved specifically into cyber terrorism and the U.S.’s current participation in a cyber war, Herzog’s approach meanders and ruminates on his subject. Structured in ten parts, each preceded by titles, the director offers several expert interviews along with his own unique, often funny, often doomsaying commentary. The resulting film does not evoke a visual awe as his documentaries Grizzly Man (2005), Encounters at the End of the World (2007), or Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), but his thoughtful and ponderous outlook remains fascinating.

After visiting the internet’s birthplace, Herzog explores a variety of perspectives on his subject, from hacking and security to robotic applications. To facilitate his musings, he interviews icons in their respective fields, including Bob Kahn, Elon Musk, and Sebastian Thrun. He talks to astrophysicists about the potential of using the internet to speak with alien cultures in distant solar systems. He asks security analyst Shaun Carpenter whether we could be in a cyber war right now and not even know it. Carpenter confirms this in an unfortunate nod, suggesting he believes what Gibney’s aforementioned doc confirms—we are already in a cyber cold war. Most sobering, Herzog interviews a family who daughter was killed in a car accident; within hours, an anonymous emailer sent photos of her body from the accident to the family. Herzog critiques the internet’s filter-free immediacy, and seems to agree with Kleinrock’s later assessment that the internet is “the worst enemy of deep critical thinking”.

Herzog’s documentaries are always at their best when they consider abstract ideas and other-worldly aspects of Nature. Consider the director’s interview with Ted Nelson. The early internet pioneer talks about his desire to transform the web into something that flows like water through his fingers. “The world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures,” Nelson says, and he wanted to bring that rather intangible idea to the web in ways that are difficult to grasp. Others in his field have since deemed Nelson to be crazed, or at least stubbornly devoted to his theories. Nelson says there are two systems of thought: The first follows Einstein’s quote, “Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” The second follows the old adage, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Nelson believes only the latter is true. As Herzog’s films Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) have taught us, people who remain so dedicated to their passions that they are willing to sacrifice their own wellbeing and reputations to realize them have always fascinated this director.

As always, Herzog remains drawn to outsiders. In one chapter, he explores a group of people afflicted by radio waves generated by cell phones and cell towers. These unfortunate people are forced to live in the wilderness far away from technology and their families, otherwise, they are afflicted by extreme pain. Still, they find joy in their unconnected lifestyle, gathering around a campfire, picking their banjos, and enjoying a simpler existence. On the other end of the spectrum, Herzog interviews former addicts who spent countless hours gaming, watching porn, and avoiding the outside world. They, too, now live in a secluded woodland getaway to recover. Each episode in the doc remains a ponderous and thoughtful one, meant to engage our imagination and consider all aspects of technology. Of course, there are purely surreal moments too, such as when he takes a cue from Philip K. Dick, asking a couple of neurophysicists, “Does the internet dream of itself?”

Lo and Behold doesn’t concern itself with an outright history of the internet or other connecting technologies, nor could Herzog’s film be called all-inclusive. Aside from Carpenter, he doesn’t ask his subjects hard-hitting questions; his experts are there merely to enable the director’s own, very thoughtful exploration, which is structured like a filmic dialogue. As with many of his documentary features, Herzog found a subject and decided to explore it with his camera crew, and then pieced it together in a loose style that might be considered a stream of consciousness. What the audience gets is not a factual probe into cyber technology, as Gibney provided. Rather, Herzog simply wants his audience to consider the many benefits of the so-called “connected” world we live in, and perhaps even more so, the potential and very real pitfalls. Herzog’s humanist approach to the documentary asks a lot of questions, and instead of providing answers, he invokes a desire to discuss these ideas on our own.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review