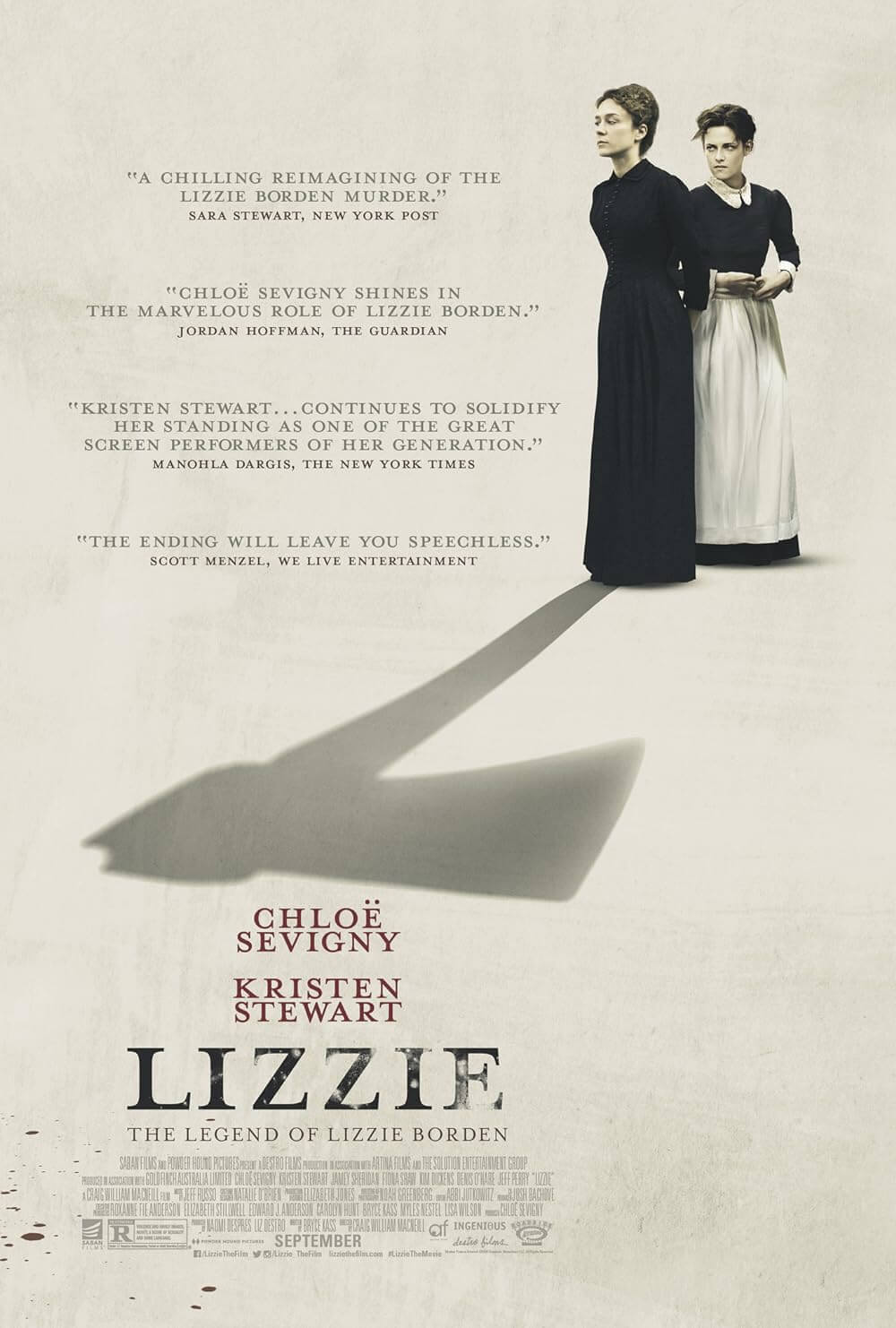

Lizzie

By Brian Eggert |

History and media culture remember Lizzie Borden as a murderer, responsible for the deaths of her father and stepmother on a hot day in August 1892. The daughter of a wealthy landowner and manufacturer, and a member of a respectable family in the high society of Fall River, Massachusetts, Lizzie became the prime suspect in the bloody hatchet killings. Though a nineteenth-century court acquitted her of the murders, the sensationalized newspaper coverage and public obsession with the case endured. Ever since, she’s been the source of countless true crime investigations, numerous books and movies, and even a creepy schoolyard rhyme (Lizzie Borden took an axe/And gave her mother forty whacks/When she saw what she had done/She gave her father forty-one). Most dramatizations and subsequent analyses of the facts resolve that Lizzie was culpable, and the sum total of their speculation has led to conjecture becoming a fact. But in the 125 years since her trial, no details have emerged that confirm Lizzie’s guilt. It’s always been assumed. Perhaps this extratextual layer to the mythos deepens Lizzie, a film that weighs the crimes with feminist compassion for her oppressive family situation, empathy for her yearnings, and reconsideration of the murders as catharsis.

Director Craig William Macneill approaches Lizzie Borden with the same sensitivity and human understanding that Anthony Minghella brought to Patricia Highsmith’s enduring character in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999). Both Lizzie and Minghella’s film get into the minds of their protagonists, exploring their emotional complexity, psychology, and motivations that led them to murder. With theories drawn from Ed McBain’s 1984 novel, also titled Lizzie, the screenplay by Bryce Kass considers the story from the mindset of a woman at the turn of the last century. When the events occurred, Lizzie was unmarried, in her early thirties, and living with her wealthy family, which her father, Andrew, kept sheltered from the outside world. By this time, Lizzie and Emma, her older sister by nine years, were old maids by the era’s standards. And yet, they were independent, fully grown women limited by their stations and robbed of their agency by a strict father, who was seemingly determined to limit their access to their inheritance. More than the practical circumstances, however, Macneill and Kass weigh the emotional conditions of being a woman in an era that rendered them powerless.

Chloë Sevigny plays Lizzie in a performance that grows with the narrative in unexpected ways. Inspired by her own fascination with Borden, Sevigny commissioned the screenplay and produced the film. And given her unconventional career, Lizzie’s perspective is just as refreshing an alternative to the Lifetime produced made-for-TV movie and subsequent series with Christina Ricci. The story finds Sevigny’s strong-minded Lizzie all but confined in her home, restricted by her entitled father Andrew (Jamey Sheridan) from going out—especially after her visit to the opera alone ends in one of Lizzie’s seizures, presumably from epilepsy. He demands that Lizzie and Emma (Kim Dickens) accept their minor role in his family, and he insists that they refer to his new wife, Abby (Fiona Shaw), as their mother. Because they are women, and therefore incapable in his mind, he will not entrust them with any say over their due finances, and in his will, he arranges, in secret, for John Morse (a wicked Denis O’Hare), his first wife’s brother, to take over the family fortune.

Meanwhile, the arrival of a new Irish maid, Bridget Sullivan (Kristen Stewart), whom Abby sneeringly renames “Maggie” after the previous house attendant, seems to intensify everything—Andrew’s demand for control, Lizzie’s resistance to being controlled, the animosity between Abby and the Borden daughters, and Lizzie’s yearning for escape. Moreover, Bridget’s presence in the house reveals the debauched hypocrisy of Andrew, who creeps into her room at night and slips under the covers as she clenches her pillow in dread. The friendship between Lizzie and Bridget gradually blooms from their shared victimhood. Lizzie teaches Bridget to read and, in her concern and spitefulness, sabotages Andrew’s nightly visits, making them apparent to everyone in their cloistered household. Their friendship also becomes a forbidden and orbital romance that, when exposed, seems to justify Andrew’s long-threatened institutionalization of his daughter for her occasional spells—a solution that would conveniently quiet his smartest and most rebellious daughter.

Meanwhile, the arrival of a new Irish maid, Bridget Sullivan (Kristen Stewart), whom Abby sneeringly renames “Maggie” after the previous house attendant, seems to intensify everything—Andrew’s demand for control, Lizzie’s resistance to being controlled, the animosity between Abby and the Borden daughters, and Lizzie’s yearning for escape. Moreover, Bridget’s presence in the house reveals the debauched hypocrisy of Andrew, who creeps into her room at night and slips under the covers as she clenches her pillow in dread. The friendship between Lizzie and Bridget gradually blooms from their shared victimhood. Lizzie teaches Bridget to read and, in her concern and spitefulness, sabotages Andrew’s nightly visits, making them apparent to everyone in their cloistered household. Their friendship also becomes a forbidden and orbital romance that, when exposed, seems to justify Andrew’s long-threatened institutionalization of his daughter for her occasional spells—a solution that would conveniently quiet his smartest and most rebellious daughter.

Macneill’s immersion into Lizzie and Bridget’s individual reality creates the sympathy necessary to retell Lizzie Borden’s tale without reducing the character to a morbid curiosity. Formally, the film uses intimate close-ups of Lizzie and Bridget’s faces, heightening the personal identification of severe moments, whether they involve romantic exploration, physical abuse, or the eventual murders. Shot in historical homes located in Savannah, Georgia, the film inhabits deafeningly quiet spaces where the wood floors—and spare, authentic details assembled by production designer Elizabeth J. Jones—make every footstep, every gesture pronounced. Cinematographer Noah Greenberg, who has partnered with Macneill on nearly every one of the director’s projects, shoots the material in natural light, drowning the night sequences in a painterly brown soup of shadows and earth tones. The frugal lifestyle insisted upon by Andrew, combined with the artistic, often lyrical minimalism of Macneill’s treatment of a melodramatic period drama, recalls what Robert Eggers accomplished on The Witch (2015). Only Jeff Russo’s understated, haunting string score threatens to treat the subject matter as merely a tale of horror, as opposed to a sad account of oppressed women pushed too far.

Structurally, Lizzie has a nonlinear form that begins as the prime suspect answers questions in an interview with authorities, and then it goes back to tell her story—not with the traditional, banal device of first-person narration, but with empathetic storytelling and form. As the screen story progresses, Macneill skips over the murders, diving straight into brief court scenes and Lizzie in jail. Alone and behind bars, her encounters with John and, later, Bridget, are among the film’s most intense. The film’s structure situates the murders at the climax, a correct choice, given that a chronological retelling might seem anticlimactic. It’s a truly shocking scene, full of primal energy as Lizzie strips down to nothing to ensure blood doesn’t stain her clothes and unleashes her suppressed rage. But when Bridget does the same, Stewart’s performance elevates to a masterful display of shuddering terror, murderous desire, and uncontrollable moral fear over what she’s about to do. Lizzie’s response is equally telling, with a dynamic that helps the viewer grasp why Bridget, who seems devoted to Lizzie and even complicit in the killing, bears a look of confusion and betrayal during the ensuing court case.

Never moralizing, Lizzie investigates the alleged Lizzie Borden killings with empathy, yet it avoids portraying Lizzie as merely a victim of her father. Although objectively the murders are revolting and gory deeds, the film’s subjectivity allows the viewer to recognize why she would go to such lengths and, while positioned in her corner, doesn’t completely absolve Lizzie of the crime. Instead, it acknowledges the necessity of action given the circumstances, but it adopts Bridget’s perspective. This is why Stewart’s performance (another great one after last year’s Personal Shopper) is so essential, despite being a supporting role. As Bridget trembles amid the oscillation of her desire to extinguish Andrew and her competing moral certainty that she cannot, Lizzie denounces the patriarchal systems that put Lizzie and Bridget in their situation and calls for understanding rather than outright castigation. Whereas history has proven that it’s easy to curse Lizzie Borden’s name and demonize her as a psychopath, Lizzie sees things in a gray zone, where her role was not that of a cold-blooded murderess but a woman who felt she had no choice but to act.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review