Living

By Brian Eggert |

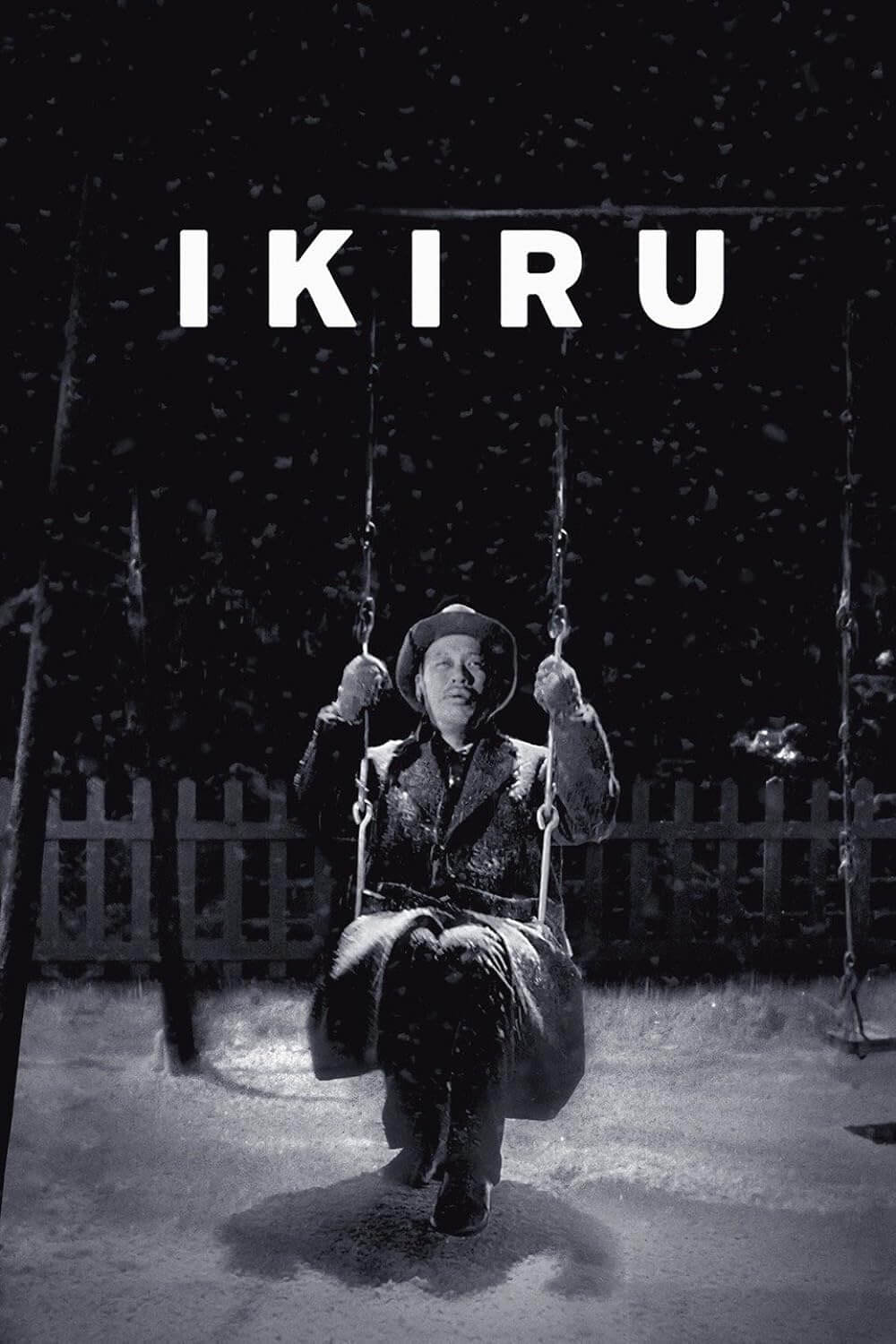

Whether it’s King Kong or Black Christmas or A Star is Born, when it comes to remakes, here’s the question: Why does this exist? The reasons vary. But in most cases, it’s a hollow commercial prospect designed to exploit the brand recognition of an earlier success. Other instances reveal a tendency to translate international hits for English-speaking audiences, allowing filmmakers to tell a good story to an audience stubbornly unwilling to engage with subtitles. In rare cases, a filmmaker offers a fresh take and improves upon or reinvigorates the original. However, Living, a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (1952), isn’t the rarified example that feels like an essential reconsideration of the original Japanese masterpiece. Watched in a vacuum and without any knowledge of the earlier film, it might play with an effective juxtaposition of stifled British manners and emotional outpouring, embodied by Bill Nighy’s aching performance. Whether or not Living will work for you, at least for this writer, depends entirely on your viewership. If you have seen Kurosawa’s original, then there’s really no need to spend time with this remake. If not, it will tug on your heartstrings, but it’s certainly not the life-affirming experience Kurosawa wrought.

The reason screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro (The Remains of the Day, Never Let Me Go) chose to revisit Ikiru after 70 years, along with the specific choices he makes in his version, remain curious. Ishiguro shifts the action from Tokyo to London; though, both versions take place in the 1950s, and the aftereffects of World War II play a significant role in each location. Director Oliver Hermanus and cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay even apply a muted, yellowish color palette in earlier scenes, which, along with the vintage-looking fonts and B-roll, give Living the appearance of a British film made not long after Kurosawa’s original—as though it were a more contemporaneous remake. As for the question Why now?, the answer is unclear. Except that perhaps Ishiguro recognized a tendency of emotional restraint in postwar Japanese culture that resembles British stoicism of the period. Aside from the geographical change, Living follows the same basic structure as Ikiru. Both versions follow a civil servant who, upon being diagnosed with terminal cancer, emerges from his repression to find meaning in his life.

Nighy plays Mr. Williams, a City Hall functionary in the Public Works department who specializes in perpetuating bureaucracy. Case in point: A group of mothers hopes to fill in a crater from wartime bombing, which is littered with dangerous debris and putrid water, and put a playground in its place. But Mr. Williams shifts their request to other departments, all of which give the mothers the runaround. Sharing a home with his selfish son (Barney Fishwick) and daughter-in-law (Patsy Ferran), Mr. Williams quietly suffers after learning he has only a few months to live. He resolves to spend some of his life savings and make his last days memorable, but he has no idea how. So he asks a stranger (Tom Burke) accustomed to a more indulgent lifestyle to show him a good time—and they go drinking, to an amusement park, and to a striptease. Later, he enjoys an impromptu lunch with a young worker (Aimee Lou Wood), who admits to calling him “Mr. Zombie,” but their platonic friendship raises eyebrows. Finally, Mr. Williams resolves to spend his few remaining weeks building the playground he had so often made someone else’s responsibility.

Similarly to Kurosawa’s film, Ishiguro’s screenplay then cuts to after the protagonist’s death, after he stubbornly worked through the bureaucracy to build the proposed playground. His coworkers wonder whether one man really could make such a difference. Herein lies the significant difference between Ishiguro’s adaptation and Kurosawa’s film. In the original, Takashi Shimura played the main character, and after his death, his coworkers mostly dismissed how one person could have such an impact. Cynical about systems of bureaucracy, Ikiru ends with few characters learning the value and importance of living life to its fullest, whereas the viewer recognizes that Shimura’s character made a difference. By contrast, Ishiguro’s worldview is far more optimistic than Kurosawa’s. Living posits that one person can have a positive impact and suggests that Mr. Williams’ coworkers will recognize his contribution. Even so, both films resolve that complacency easily captures people in its comfortable wake.

Similarly to Kurosawa’s film, Ishiguro’s screenplay then cuts to after the protagonist’s death, after he stubbornly worked through the bureaucracy to build the proposed playground. His coworkers wonder whether one man really could make such a difference. Herein lies the significant difference between Ishiguro’s adaptation and Kurosawa’s film. In the original, Takashi Shimura played the main character, and after his death, his coworkers mostly dismissed how one person could have such an impact. Cynical about systems of bureaucracy, Ikiru ends with few characters learning the value and importance of living life to its fullest, whereas the viewer recognizes that Shimura’s character made a difference. By contrast, Ishiguro’s worldview is far more optimistic than Kurosawa’s. Living posits that one person can have a positive impact and suggests that Mr. Williams’ coworkers will recognize his contribution. Even so, both films resolve that complacency easily captures people in its comfortable wake.

If Living and Ikiru have far too many similarities, the major difference between them lies in their respective central performances. Nighy is restrained compared to his otherwise typecast expressiveness, playing Mr. Williams as rigid and postured like an arrow, either from his initial stuffiness or later determination. It’s a strong performance, if somewhat less dynamic than the preceding one. Shimura seemed to hunch and curl inward, having been defeated by decades of paperwork, obedience, and inhibition—leading to his straightened transformation when he eventually finds his purpose. Still, Nighy gives his portrayal nuanced eyes, held-back emotions on the down-curved ends of his mouth, and a quiet air of desperation under every gesture. If only Hermanus directed with either Nighy’s or Kurosawa’s ambiguity. Instead, he fills most moments with Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s score that over-accents the emotions at work, particularly in the finale.

It’s perhaps unfair to judge Living against the original film, even though such conversations are inevitable regarding remakes. But after seeing that profoundly moving 1952 film, it’s impossible not to wonder whether unversed viewers will react similarly to Hermanus’ production. Ultimately, small choices in the original elevate it above the new version, which, even for the unfamiliar, may feel dully unambiguous and conventional. It has a familiar mode and execution of a lofty British drama that will undoubtedly move its audience but not shake them to the core of their being. But if viewers who enjoy Living eventually seek out the original, only to find themselves in the presence of a masterpiece, then the remake has done what some minor remakes do best—inspire us to seek out their betters.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review