Little Woods

By Brian Eggert |

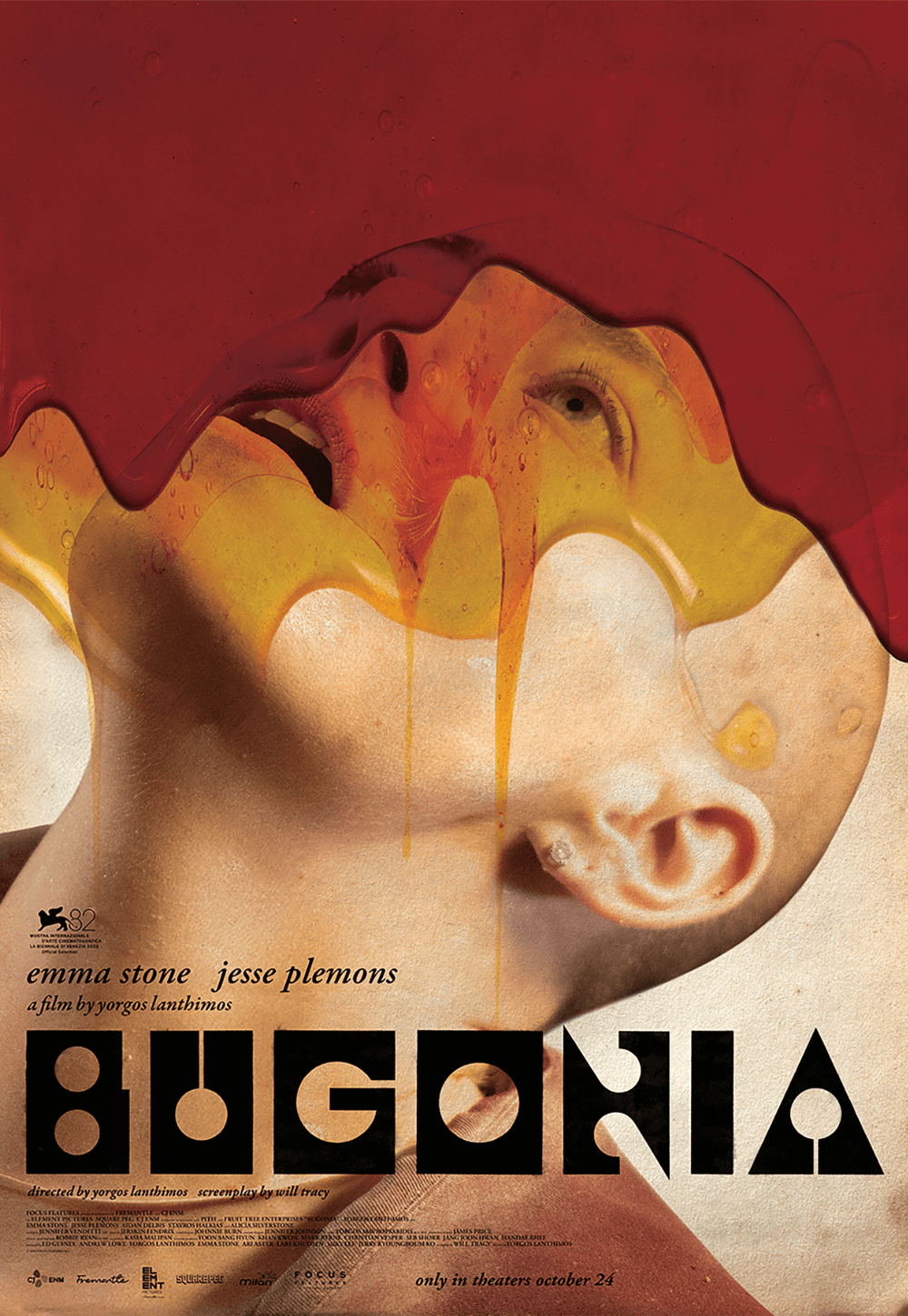

The sound of a shovel penetrating the ground is always an ominous sign in a film. It evokes thoughts of a burial, which is never a good thing in the context of a thriller. In the first moments of Little Woods, the sound we hear is not the internment of a body; it’s the frantic covering-up of prescription drugs illegally carried over the border from Canada to North Dakota. While the current presidential administration commits crimes against humanity to prevent entry into the United States at the Mexico border, Americans reenter the country from the northern border with their score of pills to further the opioid epidemic. Writer-director Nia DaCosta uses this setting for her debut film, a slow-burning tale of poverty and limited options that gradually closes-in on the viewer with a claustrophobic sense of tension.

Set in the title’s fictional North Dakota town built around the local oil industry, this so-called rural noir has a streak of misery porn running through it. Tessa Thompson and Lily James star as sisters Ollie and Deb, who stand to inherit their mother’s house, a ramshackle place that their paltry income cannot afford. Ollie, a doer that every other character seems to admire, used to work as a drug mule and sell prescription medication to the local oil workers. She’s since been caught and is serving probation; she’s also living in the skeletal remains of her mother’s house, and the evidence of a prolonged illness surrounds her. Deb, a single mother with a perpetually sick child, lives in an abandoned van in a parking lot. She serves tables at a local bar, but it’s not enough to provide for her son or the baby that’s on the way. Inevitably, their situation is so impossible that Ollie vows to return to dealing only until she can provide a stable situation for her sister and nephew.

DaCosta creates an uneasy level of stress (which I will avoid calling suspense) through a number of narrative devices that constrict the characters and create pressure. Several time elements provide tension-building countdowns: Ollie has just a few days left before she’s free of her probation officer (Lance Reddick); the bank has agreed not to foreclose on their mother’s house if the sisters can come up with a few thousand dollars in a week’s time; Deb needs an abortion, as she can’t possibly afford to have the child, but the clock is ticking. Money exacts another kind of pressure: the sisters need to raise money for the bank; Ollie needs money to support her sister; before she decides to have an abortion, Deb learns that it costs around $9,000 to have a child, which is money she doesn’t have. And just as Ollie’s plan inches them closer to freedom, a local crime boss demands thirty percent of Ollie’s deals, setting back all of her progress. There comes a point, however, when you can feel DaCosta sacrificing the story’s gritty realism as she piles on the endless sources of bad luck.

Although Little Woods was advertised as a thriller, it works better as something quieter, more akin to Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone or Leave No Trace. The film unfolds gradually, building the aforementioned burdens of time and money through nuanced character work. Thompson and James have rarely given such measured, intentional performances. Both are better known for high-energy work such as Thor: Ragnarok, Baby Driver, 2015’s Cinderella, Sorry to Bother You, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and more recently Yesterday and MIB: International. In the last few years, they’ve both averaged several projects per year, but Little Woods is among their best individual work, even if the overall film feels somewhat underwhelming. By the end of DaeCosta’s pressure-cooker scenario, the situation takes an unlikely and even optimistic turn, and somehow that feels uncharacteristic for everything that came before. Then again, viewers who are drawn to a happy ending, regardless of whether or not it matches the film’s tenor, will be pleased by this deviation.

DaCosta shows her obvious talent in this, her debut film (no wonder Jordan Peele tapped her to direct the “spiritual sequel” to 1992’s Candyman). She maintains a considerable degree of control over the bleakly colored, ever-overcast proceedings to reflect the morally ambiguous decisions made by Ollie and Deb. Her cinematographer, Matt Mitchell, shoots in either unobtrusive medium and master shots, or he uses frenzied hand-held camerawork for the amped-up scenes. But formally, DaCosta’s style is subdued and hardly the focus. Where she excels is her manipulation of tone. She builds tension through situations that make us squirm or think, “Could it get any worse?” Alas, it doesn’t. Had the film built to something more tragic than hopeful, Little Woods may have had greater resonance. Regardless, Thompson and James command our attention, and DaCosta has given them a number of scenes that offer superb acting. Sometimes that’s enough.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review