Little Women

By Brian Eggert |

Greta Gerwig’s new adaptation of Little Women doesn’t open in the same place as Louisa May Alcott’s essential 1868 novel, which began with the March family discussing their poor Christmas. Instead, in the first images, Saoirse Ronan’s Jo March takes a deep breath before entering the offices of a newspaper editor named Dashwood (Tracy Letts). She hopes to sell one of her short stories, though to protect herself from the humiliation of rejection, she hides her inky fingers and claims to be an intermediary for a friend. Dashwood reads through the pages on the spot. As Jo watches, he crosses out whole paragraphs and slams each completed page on his desk as if swatting a fly. She begins to wither in disappointment. But much to her surprise, he agrees to buy the story. It’s a glorious moment for the young woman who lives in a time when there are “precious few ways for women to make a living” without marriage or coming from money. Whatever hesitations she had about her creative pursuits dissolve into an exhilarated journey home. She races through the streets of New York in a state of elation and liberation. The moment cannot help but recall when Gerwig’s character in Frances Ha (2012) runs and twirls through the streets of New York with those same feelings. Both films, and all of Gerwig’s work as a writer or director, contain a similar theme of young women growing into and celebrating themselves.

As the voice behind the latest adaptation of Alcott’s classic, Gerwig finds parallels between the author, Jo March, and herself. She intuits their shared creative ambitions, and in doing so, revitalizes the material for a new generation of viewers—and hopefully readers. Just as Alcott put herself into Jo, the second oldest of four Massachusetts sisters in the 1860s, and a budding author in a field dominated by men, Gerwig, in only her sophomore directorial effort after her 2017 breakthrough Lady Bird, emphasizes the importance of women as creatives. The first and last scenes of Gerwig’s Little Women concern Jo’s fulfillment as an author. Though the writer-director maintains Alcott’s basic story that Jo emerges as a writer and, eventually, marries a professor with whom she falls conveniently in love, Gerwig downplays the importance of marriage—she even underlines how silly it is that Jo gets married. In bookend scenes between Jo and Dashwood, the editor demands that her fiction ought to end with the heroine’s marriage or death. Gerwig, who no doubt looked at Alcott’s legacy as an author and recognized she lived happily as an unmarried woman until her death in 1888, stressed that women have more to offer than the roles assigned to them by men. And while Gerwig concedes to the character’s marriage in the end, if only out of faithfulness to the source material, she suggests the obligatory nature of the marriage and invents an altogether more satisfying finale.

The film follows in the long procession of adaptations to film and theater, not to mention the stuff of musicals, radio plays, and television miniseries. Hollywood has turned out several features based on the novel, including two silent-era films, George Cuckor’s adaptation from 1933 starring Katherine Hepburn, Mervyn LeRoy’s color version in 1949, and Gillian Armstrong’s 1994 film featuring Winona Ryder. Just last year, a contemporary-set adaptation directed by Clare Niederpruem, and produced by various Christian groups, came and went without notice. But Gerwig translates the novel with a new purpose and structure, deviating from the methods of the past, which tend to treat the bisected text as two distinct and linear parts, just as they were published—even to the extent of using different performers for the second half when the characters have aged by a few years. Using the same cast throughout, Gerwig and her editor Nick Houy rearrange the events in the book to find dramatic corollaries between scenes as Jo and her sisters negotiate times of sickness, romance, and creative blocks. It’s an intuitive approach that feels modern, imbuing individual segments of the film with thematic heft, while also maintaining a sense of active viewership in an audience already familiar with the material.

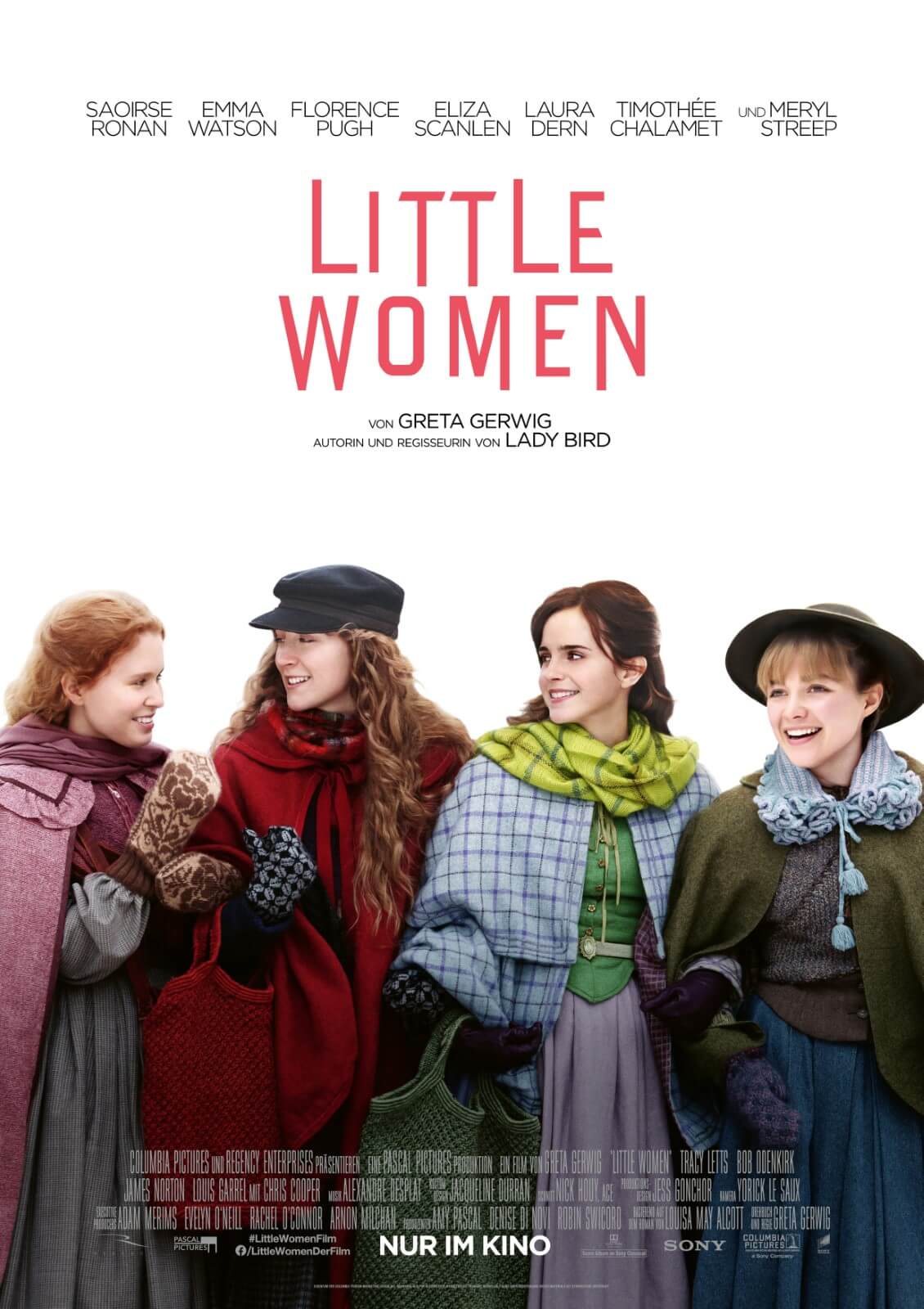

After names like Armstrong and Cuckor, Gerwig follows stiff competition, though her version of Little Women captures the feminist edge of the text while accentuating its timelessness with inspired flourishes. Best of all, the cast is superb, beginning with Ronan at the center. She’s the focal point of the story, and the daughter who most resembles the sisters’ mother, Marmee (Laura Dern), an independent woman who must abide as her husband (Bob Odenkirk) fights in the Civil War. In a tender scene taken from the novel, Marmee confesses, “I’m angry nearly every day of my life”—an admission that affirms how New England women of this period had to be masters of external control. However prim and proper they might appear on the outside, there’s a spiritedness on the inside, found in Alcott’s lovingly detailed characters. There’s the oldest daughter, Meg (Emma Watson), a pragmatist determined to settle down and start a family. The shiest and most charitable of them is the sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen), who hides her talent for the piano behind her timidity. The youngest, Amy (Florence Pugh), dreams of greatness as a painter, though she recognizes the economic necessity of marriage for a woman of her time. While others give glowing performances, Pugh steals the film as she alternates among Amy’s states of vulnerability, jealousy, and unruliness. In the company of Ronan and Pugh, Watson and Scanlen can’t help but recede.

After names like Armstrong and Cuckor, Gerwig follows stiff competition, though her version of Little Women captures the feminist edge of the text while accentuating its timelessness with inspired flourishes. Best of all, the cast is superb, beginning with Ronan at the center. She’s the focal point of the story, and the daughter who most resembles the sisters’ mother, Marmee (Laura Dern), an independent woman who must abide as her husband (Bob Odenkirk) fights in the Civil War. In a tender scene taken from the novel, Marmee confesses, “I’m angry nearly every day of my life”—an admission that affirms how New England women of this period had to be masters of external control. However prim and proper they might appear on the outside, there’s a spiritedness on the inside, found in Alcott’s lovingly detailed characters. There’s the oldest daughter, Meg (Emma Watson), a pragmatist determined to settle down and start a family. The shiest and most charitable of them is the sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen), who hides her talent for the piano behind her timidity. The youngest, Amy (Florence Pugh), dreams of greatness as a painter, though she recognizes the economic necessity of marriage for a woman of her time. While others give glowing performances, Pugh steals the film as she alternates among Amy’s states of vulnerability, jealousy, and unruliness. In the company of Ronan and Pugh, Watson and Scanlen can’t help but recede.

Fortunately, Little Women doesn’t share much in common with Cuckor’s 1939 film The Women, which failed the Bechdel test with its tagline: “It’s all about men!” Men feel like outsiders in the March home; even their father, who doesn’t show up until the last third of the film, seems like he hardly belongs in the March’s company. The only constant male presence remains Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), a handsome neighbor who shares the same impulsive energy as Jo. They’re in love, of course, but they realize this at different times, and they stay out of sync. Laurie’s somber grandfather (Chris Cooper) owns an estate not far from the March home, just a glance out the window. Beth’s eventual submission to scarlet fever might affect him as much as her sisters, if only because Beth reminds him of his late daughter. Elsewhere, Gerwig revises Alcott’s story to give Jo a more promising future than the novel does. Alcott left Jo in the hands of a cerebral German professor, whereas Gerwig dreams up a more fitting fantasy in the form of an attractive French intellectual (Louis Garrel). His arrival in the final scenes is nothing short of improbable, a choice driven by Alcott’s publishers. But as Dashwood explains with a rare touch of sentimentality that Letts’ delivery justifies, “It’s romance.”

The film’s nonlinear chronology allows Gerwig to return to the March house as a kind of warm, inviting haven. Every scene that cuts away from the interior space feels removed from the familiarity of the household, even though its appearance changes through the seasons. Gerwig and her production designer Jess Gonchor based the March household on Alcott’s actual home, but they enliven interior spaces to reflect the characters. Cluttered tabletops and large rooms where the young women have enough space to perform homespun plays or lose themselves in raucous disagreements, change depending on the scene. Nothing looks as though Marmee had decorated each room in the same manner for years. It’s a home, albeit a set-piece, that appears to be vibrant and continuously lived in—evidenced by the rambunctious clatter of shoes on the wooden stairs or the morning sun that fills its rooms with orange light. By contrast, Gerwig makes Amy’s trip to Europe or Jo’s time in New York feel somehow cold, transitioning to blue and green hues for the March women’s experiences away from the family. But when we return to scenes at the March household, even in frigid winter scenes or Beth’s times of illness, it feels like a welcome return home.

Gerwig’s nonlinear structure also allows for visual variation from scene to scene, as the times and places visited in Alcott’s story each has a distinctive look thanks to cinematographer Yorick Le Saux—a frequent collaborator with Olivier Assayas (Personal Shopper) and Luca Guadagnino (A Bigger Splash). Instead of whole periods of time having a unique look and then fading into memory, Gerwig instills a new visual and dramatic rhythm that revisits times and places, from the honeyed first half of Alcott’s story to the more determinative second half. And Little Women is also a gorgeous looking film, perhaps the most richly realized of all the book’s adaptations. The costumes by Jacquelin Durran, especially those of the Marches, look worn and thrown together in a loving way—garments hastily assembled to keep warm and contain the wearer’s personality, Jo’s above all. More classical costumes appear at a local ball or in the home of their cynical, wealthy Aunt March (Meryl Streep), who gives up trying to convince Jo to marry well and support their family; she eventually turns her efforts to Amy, who recognizes the importance of formality but doesn’t suppress her desires. Shooting on 35mm, Le Saux captures these costumes in vibrant, textured colors that feel realistic and natural, and far removed from the rosy theatricality of previous versions.

Gerwig’s nonlinear structure also allows for visual variation from scene to scene, as the times and places visited in Alcott’s story each has a distinctive look thanks to cinematographer Yorick Le Saux—a frequent collaborator with Olivier Assayas (Personal Shopper) and Luca Guadagnino (A Bigger Splash). Instead of whole periods of time having a unique look and then fading into memory, Gerwig instills a new visual and dramatic rhythm that revisits times and places, from the honeyed first half of Alcott’s story to the more determinative second half. And Little Women is also a gorgeous looking film, perhaps the most richly realized of all the book’s adaptations. The costumes by Jacquelin Durran, especially those of the Marches, look worn and thrown together in a loving way—garments hastily assembled to keep warm and contain the wearer’s personality, Jo’s above all. More classical costumes appear at a local ball or in the home of their cynical, wealthy Aunt March (Meryl Streep), who gives up trying to convince Jo to marry well and support their family; she eventually turns her efforts to Amy, who recognizes the importance of formality but doesn’t suppress her desires. Shooting on 35mm, Le Saux captures these costumes in vibrant, textured colors that feel realistic and natural, and far removed from the rosy theatricality of previous versions.

Gerwig’s most inspirited reworking of Alcott’s novel isn’t so much a departure as a renewed set of priorities. Though Jo’s passion for remaining an independent woman and becoming a professional writer leads to her romantic undoing with Laurie, she is committed. Her desire to write has been implanted into scenes with the younger March sisters, such as when they practice the Christmas play Jo authored or the many scenes of Jo scribbling away on a short story all night in the attic. It continues in her impassioned speech to Marmee, which Gerwig borrows from a different Alcott text, Rose in Bloom: “Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty, and I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for. I’m so sick of it!” Gerwig avoids creating an altogether new ending where Jo turns into Alcott and becomes “a spinster”—the term Dashwood uses when he warns that Jo’s eventual book, entitled Little Women, cannot end with the heroine alone, living as a writer. But she includes the scene between Jo and Dashwood to stress that such endings belong in fiction, whereas in reality, a timeless piece of literature, one that has remained vital and revisited for over 150 years, can be penned by a woman alone.

Alcott’s story, and Gerwig’s marvelous adaptation of it, find happiness for the Marches in a range of forms. Meg feels loved in her domesticated life with a modest tutor, John Brooke (James Norton), and Amy at last finds love with the rich and irresponsible boy next door, experiencing more than one erotically loaded scene in Paris before marrying off-screen. For Jo, Gerwig allows the newspaper editor his prescribed conclusion. “If I were a girl in a book, this would all be so easy,” Jo says at one point, and so it is. Her marriage to the dashing French professor is a kind of conclusion, satisfying the romantic requirement of those committed to traditional happy endings. But after that, in the final images of Little Women, Gerwig does one better, demonstrating that the legacy of people like Alcott, and thus Jo, belongs not to their romantic fulfillment but the piece of them left behind in their work. It is a leather-bound legacy, imprinted and gold-foiled, and cherished by countless readers. While Little Women proves thoughtfully constructed, lovingly made, terrifically performed, and a viewing pleasure, Greta Gerwig’s film also contains an inspiring message for young women determined to create.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review