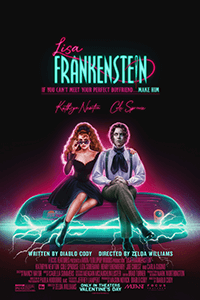

Lisa Frankenstein

By Brian Eggert |

Lisa Frankenstein is a teen movie sewn together from various body parts, each unearthed from a graveyard of old influences. Set in 1989, it contains a streak of outmoded ‘80s nostalgia that has been tediously overdone for years. The scenario features a Tim Burton-esque juxtaposition of suburban banality and silent-era expressionism reminiscent of Edward Scissorhands (1990), with a murderous hint of Heathers (1988). And its narrative boasts a venerable motif—the romantic pairing of a young woman with a monster, evidenced in everything from the original Beauty and the Beast fairy tale to the more recent girl-with-zombie yarn Warm Bodies (2013). At the same time, it’s a modern(ish) retelling of a classic with a genre bent, akin to Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016), except instead of adding monsters to a romance, it adds romance to the setup of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. After screenwriter Diablo Cody patched her various allusions together in script form, she handed the material off to director Zelda Williams, who makes her feature debut. But Williams never imbues the material with enough electricity. If a bolt of lightning was needed to bring this patchwork to life, Lisa Frankenstein receives no more electrical current than the zing one gets from licking a nine-volt battery.

Derivativeness alone cannot derail a movie, but it becomes a hindrance when neither the narrative nor the characters rise above it. The setup follows a teen outcast, Lisa (Kathryn Newton), whose mother was slaughtered by a masked killer and has since been understandably introverted. Her father, Dale (Joe Chrest, playing an identical role to his Stranger Things character), has remarried to an evil stepmother, Janet (Carla Gugino). The marriage also supplied Lisa with a step-sister, the upbeat cheerleader Taffy (Liza Soberano), who has the best of intentions in trying to “socialize” her new sibling. The new girl at Taffy’s school, Lisa, whose pink bedroom walls are adorned with posters from A Trip to the Moon (1902) and various Universal monster movies from the 1930s, prefers the strange and unusual. She spends her time in a nearby cemetery, talking to a crumbling gravestone topped by the bust of a nineteenth-century hunk. With the help of some lightning from an inexplicably green cloud, Lisa wills her crush (Cole Sprouse)—whose gravestone reads “Frankenstein,” though it’s unclear if he’s meant to be Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein—back to life.

Cody’s script is particularly unfocused, juggling several disparate story threads and tones inharmoniously. When Lisa revitalizes the rotting corpse of Frankenstein using Taffy’s malfunctioning tanning bed, each use makes the walking corpse look a little more human and alive. Soon, Lisa’s groaning, undead friend and eventual lover doesn’t just supply her with a companion; he also teaches her to come out of her shell, instructing her how to dress through grunts in a familiar closet montage sequence. But rather than fall for her undead dreamboat, she has a crush on her school’s literary magazine editor (Henry Eikenberry), so her romance with Frankenstein never feels genuine, just secondary. At the same time, Frankenstein disposes of some unwanted people in her life—and Lisa helps conceal the crimes. From them, Lisa obtains parts missing from Frankenstein (an ear, a hand, and eventually more) and sews them back on. All of this leads to tension-less scenes where Lisa tries to keep her monster a secret while covering their murderous tracks from her parents and authorities.

Cody revisits a theme from her script for Jennifer’s Body (2009), exploring the monstrous behavior of teens through a horror metaphor. Here, Lisa, both traumatized and misunderstood, rejects and lashes out at the world because she cannot find her place within it. However relatable that may be, it’s contained within a scatterbrained structure. With all of its shifts in genre and style, a dexterous hand was needed behind the camera. Williams can’t manage it, and she receives no help from editor Brad Turner, who delivers one stiff, unenergetic scene after the next. The half-hearted score by Isabella Summers barely registers, never punctuating or adequately supporting the mix of humor, horror, and romance as, say, Danny Elfman often does in early Burton movies. The general flatness of Lisa Frankenstein is surprising, given Cody’s tendency to write punchy scripts. Say what you will about her past work; they’re never dull. They usually crackle with personality. Here, the material feels lobotomized.

Cody revisits a theme from her script for Jennifer’s Body (2009), exploring the monstrous behavior of teens through a horror metaphor. Here, Lisa, both traumatized and misunderstood, rejects and lashes out at the world because she cannot find her place within it. However relatable that may be, it’s contained within a scatterbrained structure. With all of its shifts in genre and style, a dexterous hand was needed behind the camera. Williams can’t manage it, and she receives no help from editor Brad Turner, who delivers one stiff, unenergetic scene after the next. The half-hearted score by Isabella Summers barely registers, never punctuating or adequately supporting the mix of humor, horror, and romance as, say, Danny Elfman often does in early Burton movies. The general flatness of Lisa Frankenstein is surprising, given Cody’s tendency to write punchy scripts. Say what you will about her past work; they’re never dull. They usually crackle with personality. Here, the material feels lobotomized.

The movie’s aesthetic is just as misguided. Apart from the inspired black-and-white title sequence, animated to look like Gothic silhouette portraiture, and a later dream sequence that looks as if Bride of Frankenstein (1935) were directed by Robert Wiene, much of Lisa Frankenstein appears generic. Newton, great in Freaky (2020), seems to be doing some manner of Elsa Lanchester in her performance, but it never quite lands. Sprouse, who played a “Frankenstein” once before in Big Daddy (1999), doesn’t have much to work with. His simplistic character grunts and moans, with his performance drawing from Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931) and Sherman Howard’s Bub from Day of the Dead (1985), which plays on a TV in one scene. But given all the classic cinema influence, the material seems ripe for a Burton-brand visual treatment, with a heightened production design that’s just as imaginative as the concept. Instead, the visual presentation feels dialed down, when form-follows-function logic suggests it should be larger-than-life.

The experience didn’t prompt a single laugh or much response at all from me, nor did it impress in technical terms, making uninspired use of its many stylistic forebearers. Perhaps more skilled hands could have brought life to Cody’s script. Then again, the romantic appeal of a dead person, no matter how chivalrous—or, underneath the surface-level decay, cute—has never appealed to me. Dead is dead, even in zombie romance fiction. So, movies such as the aforementioned Warm Bodies are antithetical to me, even as a tongue-in-cheek genre experiment, unless the zombie romance takes place in a stylistically heightened world (see Fido, 2006). Lisa Frankenstein didn’t overcome my innate aversion. When Lisa decides to make love with her undead partner, newly equipped with a member they’ve stolen from one of their victims and sewn onto Frankenstein, the romance of the moment only produced revulsion. But then, no aspect of Lisa Frankenstein worked for me—not the human-monster romance, not the macabre humor, not the uneven performances, not the routine visuals, not Cody’s familiar remarks on teendom. Occasionally, as a critic, I come across movies that don’t deliver on any level for me. Lisa Frankenstein is one of them.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review