Life of Pi

By Brian Eggert |

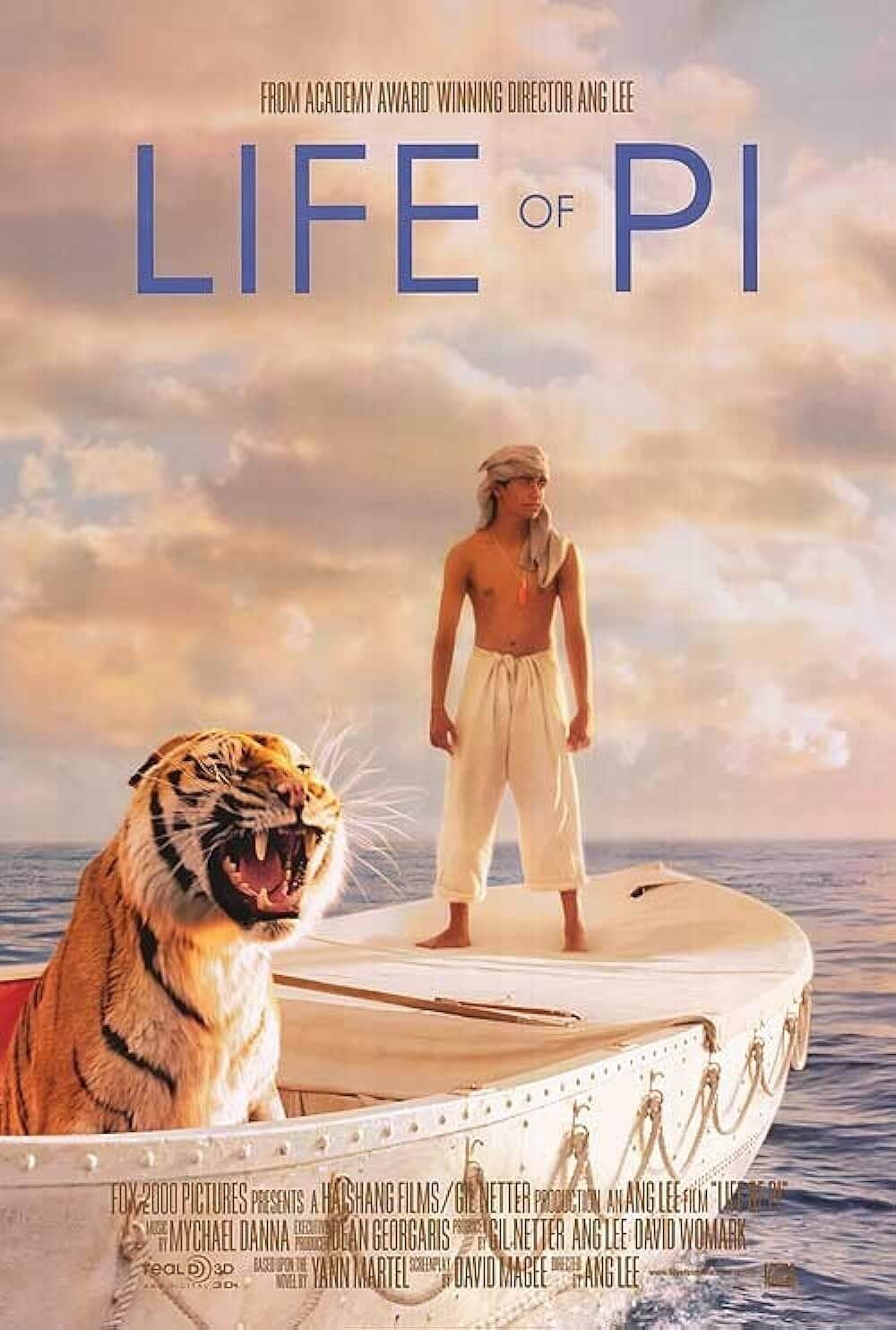

In Ang Lee’s Life of Pi, a marriage between spiritual faith and the wonder of the natural world offers audiences a reflective parable for religious understanding and even the very nature of storytelling. The harrowing tale involves an Indian boy and a Bengal tiger on a lifeboat in the Pacific for several months, and as they battle each other for territorial superiority, the human and the animal begin to understand each other. Through their exchange, the screenplay by David Magee, based on Yann Martel’s 2001 novel, meditates on how as individuals, we see the world as we choose to see it—whether that be the emotions we observe in animal behavior, the meanings we project onto events in our lives, or how we amplify our experiences for effect. Through the course of the film, we take part in a beautiful worldview, rich with visual spectacles and a spiritual epiphany that even the most devout cynics will cherish.

The film opens in Pondicherry, a former French colony in India, where the family of our young protagonist, Piscene Patel (played at age 12 by Ayush Tandon), runs a zoo. Schoolboys remind him that his name, taken from the French word for “swimming pool,” sounds like “pissing,” and so he changes it to Pi and establishes his nickname by memorizing the mathematical constant’s neverending tail. An inquisitive sort, Pi was raised Hindu, but to understand God, he explores Christianity and Islam as well, adopting trademarks from each religion for his own uses, much to his strict father’s dismay. When Pi’s father must sell the family zoo and the animals, he books passage to Canada aboard a Japanese ship. Pi—now a teenager and played by Suraj Sharma, an inexperienced actor who shows astounding range, is forced to leave his home and the young dancer (Shravanthi Sainath) with whom he’s fallen in love. In rough seas over the Marinas Trench, the Japanese ship sinks, Pi’s family dies, and he’s left on a 20-foot lifeboat with a single rat, a ravenous hyena, an injured zebra, a protective orangutan, and a large Bengal tiger known as “Richard Parker.”

When the inevitable collision of hunger and territorial clashes subside, Pi is left floating on a makeshift raft connected by rope to the main lifeboat, which Richard Parker has conquered. Two hundred twenty-seven days pass as man and beast attempt to coexist, and the film carefully spells out how Pi and Richard Parker form a unique trust over battles for food and space under the lifeboat’s protective tarp. Together they witness tremendous sights, from a wave of flying fish to a bioluminescent ocean surface breached by a whale, from another massive storm to a green living island populated by meerkats. Structurally, Pi’s adventure is bookended by modern-day scenes in Canada, where a wise middle-aged Pi (Irrfan Khan) recounts his adventure to a skeptical Canadian author (Rafe Spall) looking for his next book’s inspiration. At the very beginning and end, the film alternates between scenes in Pi’s contemporary home and flashbacks to his life’s story, while the central piece of the story remains Pi’s account of his survival.

At no point in the film does Lee betray the viewer’s suspension of disbelief, despite the vast use of computerized special effects employed to make these otherwise inconceivable movie moments come to life. The effects used to render the zoo animals throughout the picture are nothing short of amazing, particularly the CGI employed for Richard Parker. Although many scenes using four different tigers were shot, much of Richard Parker’s behavior would have been impossible for trainers to safely allow for a live animal, and the integration of real-life and computer-generated imagery is flawless. Wild attacks and even a seasick tiger are realized brilliantly, while the film’s sinking ship sequence contains a haunting exquisiteness. Shot in various international locales in Montreal and India, the production required Lee’s crew to build a massive tank in Taiwan for the sea sequences, each augmented by a vast amount of artificially designed imagery. The splendor inhabiting every frame of Pi’s seafaring survival story displays a painterly quality added to the horizon where the water and sky meet, and therein reflect one another in fantastic, illusory ways.

Lee’s visual mastery also makes the best use of the 3D device yet, even better than James Cameron’s Avatar, or any number of stop-motion animation projects to showcase the effect. It’s not that Lee sends animals reaching out to touch his audience; rather, he gives the adventure depth and space. Water seems to exist on an expansive surface, and with Pi’s lifeboat often a speck on this open plane, Lee truly places his viewer in the scene in ways no filmmaker has conceived before. At other times, Lee manipulates his aspect ratios to better frame a scene or action. At one point, the rectangle frame becomes a pan & scan square with Pi’s boat in the center, accentuating his isolation in the open sea. During the flying fish stampede, the film’s 1.85:1 frame widens to 2.40:1, and we follow a daredevil tuna chasing after its prey, the hind fin just bleeding out of the frame’s margins to enhance the effect. Such details occur throughout Life of Pi, but they never take precedence over the spiritual significance of the story.

Because of its more extravagant elements, Martel’s source text was considered technically unfilmable for years, and after several other directors left the project (among them M. Night Shyamalan, Alfonso Cuarón, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet), the pronounced challenges attracted the Taiwan-born American director. Lee’s diversity of projects begins with cherished period dramas Sense and Sensibility (1995) and The Ice Storm (1997), continues through his martial arts reinvention of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), and achieves rare explorations of intimacy in Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Lust, Caution (2007). But then, Lee is also capable of realizing grand epics such as the underseen Civil War piece Ride with the Devil (1999) or bringing a cartoony quality to expressive superheroes with Hulk (2003). He finds a perfect balance between the emotional profundity of his past efforts and his own visual ambition in Life of Pi, a project that sets a bold new standard for the use of 3D and CGI but also has a thoughtful and understanding message inside an incredible visual experience.

Early in Life of Pi, the Canadian author is told Pi’s story will make him believe in God, but perhaps a better assessment is that this tale will invoke a sense of understanding toward religions and stimulate an exploration of faith. The ways in which this is accomplished in the film an audience should discover for themselves. But when Pi’s inevitable survival comes to pass, the film ends by asking questions about what we have seen and how we interpret what has happened. What this critic has seen is a marvelous piece of visual poetry with insights that require contemplation long after the visual awe has subsided. Lee has created a superbly balanced motion picture that moves special effects and 3D beyond the realm of pure entertainment augmentation; where other films use such technical modes for thrills alone, Lee creates a breathless experience both visceral and philosophical—and also unforgettable.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review