Life Itself

By Brian Eggert |

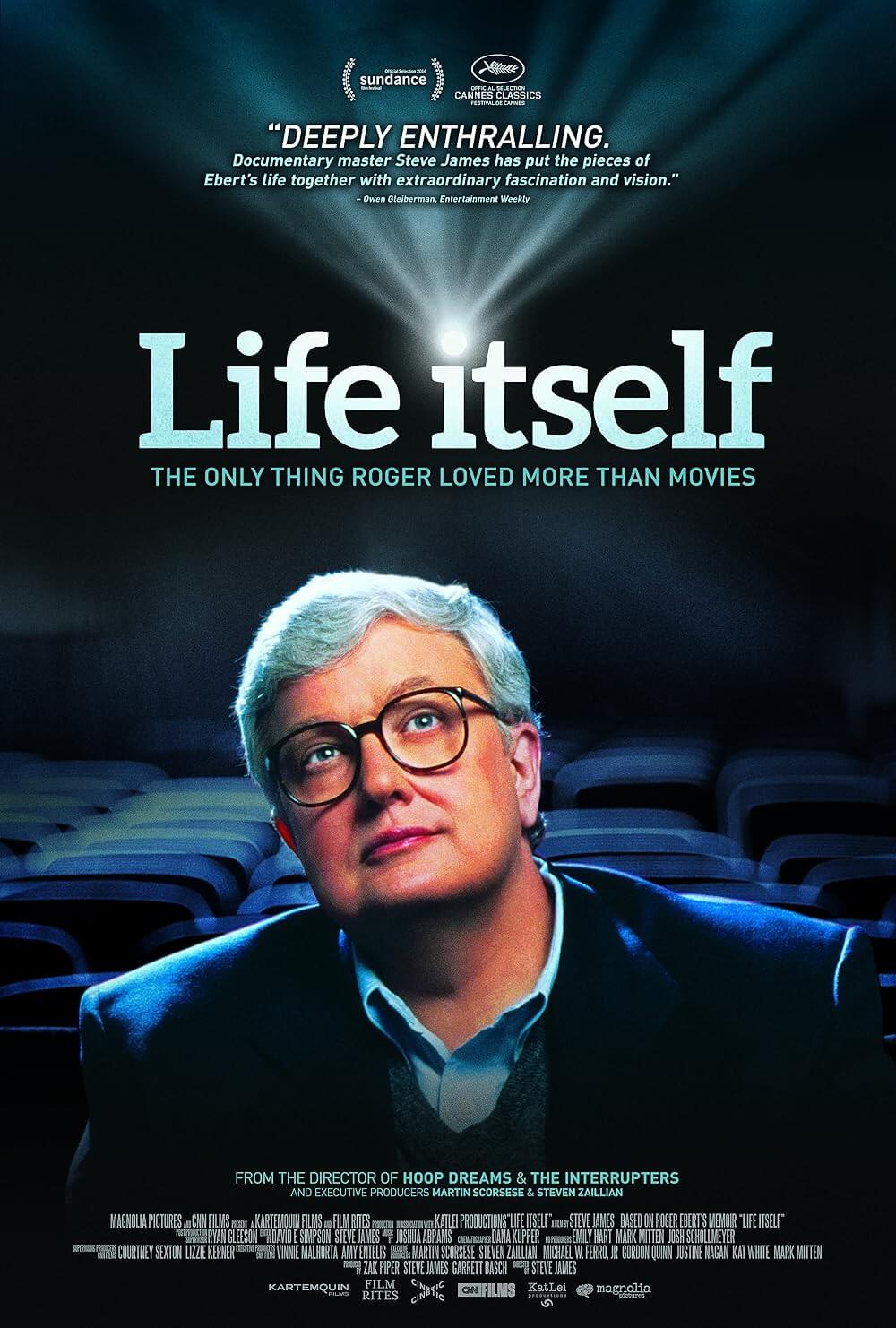

It’s impossible to overstate the influence of Roger Ebert on film criticism, film-making, and pop culture in general. One would also be hard-pressed to make too much of Ebert’s impact on the people around him, from his wife Chaz and their family, to filmmakers like Martin Scorsese or Errol Morris, whom he encouraged to make better films. One of those filmmakers was Steve James, the documentarian whose film Hoop Dreams was championed by Ebert in 1994. James and Ebert planned to make a documentary together about Ebert’s life, which would include an overview of his impactful career and feature several interviews with those close to him. Life Itself is the end result and, borrowing its title from Ebert’s 2011 memoir, it doesn’t attempt to blindly exalt the late film critic; rather, the film provides a moving epitaph of Ebert’s career and a sharp, but affectionate, examination of the man.

When James set out to make his documentary, Ebert, virtually confined to a wheelchair, had been fighting various cancers for years. He was still writing reviews intermittently and maintained his insightful blog, but his lower jaw had been removed and he spoke using a computerized voice on his laptop. While James was filming, Ebert’s cancer returned, and the prognosis was anywhere from 6 to 16 months; he would live another 3 months after the diagnosis, not long enough for he and James to finish their original plan for the doc. The film then became part autobiography and part farewell. The structure contains intimate scenes from Ebert’s rehabilitation work and hospital stay where Chaz and family are by his side, and then intercuts those scenes with a detailed history narrated by a convincing sound-alike reading from Ebert’s book. The footage James captures of Ebert’s last days is both difficult to watch and inspiring to behold. It’s inspiring because his words are his voice and, through his robotic speech, the tone and power of his words are the same old Roger we love.

James delves into Ebert’s history, beginning with his self-published neighborhood newspaper, his early days as a shrewd college newspaper editor, his heavy drinking during his initial years at the Chicago Sun-Times, and his emergence into film criticism. Anecdotal curiosities, such as Ebert’s screenwriting gig for Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) or his downright hatred for Blue Velvet (1986), prove riotously entertaining. And if there’s a “fun” part of this doc, it’s the segment focused on Ebert’s tumultuous rivalry with Gene Siskel and his presence in the film critic culture at large. (The outtakes where Siskel and Ebert squabble like schoolboys is hilarious.) Being the first of his kind to win a Pulitzer Prize, Ebert became confident, some would say arrogant, and his wealth and popularity from Siskel and Ebert’s “two thumbs” trademark only intensified his superiority until he met Chaz. Her openness, vulnerability, patience, and devotion to Ebert are contained in touching hospital scenes, taking us further into Ebert’s illness than some would choose to go. But after Gene Siskel died in 1999 of brain cancer and told no one of his diagnosis except his closest family, Ebert resolved to make his fight with cancer an open book.

Meanwhile, James’ interviews with Ebert’s associates and friends—such as A.O. Scott, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Howie Movshovitz—acknowledge the downside of Ebert’s approach, where he reduced film analysis down to an upright or down-turned thumb. But Siskel and Ebert also popularized film criticism and made the vocation what it is today—an accessible form of critical expression, contrary to elitists like Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael (“Fuck Pauline Kael!” says one of Ebert’s colleagues). As Ebert argued with Richard Corliss after the critic censured Siskel and Ebert’s almighty thumb in Film Comment, the show was not meant as expansive film analysis; rather, it was a forum to give recommendations and to expose viewers to films that general audiences might not otherwise hear about. Moreover, Ebert’s reviews explored the kind of readings that anyone could understand, and therein spread his contagious love of cinema. There was a host of young writers inspired to write about movies because of Ebert’s example, and there was a film-savvy internet culture that lost its most prominent voice when he died in 2013.

Life Itself handles Ebert’s heyday as a critic and his life with Chaz extremely well. (Though, it glosses over some of his post-Siskel life, such as Ebert’s association with Richard Roeper.) As an independent online film critic whose desire to write about movies was, in part, born from Ebert’s insightful reviews and the Siskel & Ebert and the Movies television show, my own professional hobby was shaped by Ebert. And when I sat down to watch the engrossing story of his life, I could not help but feel profoundly affected, if later resistant to the idea of reviewing a film for which I am undoubtedly partial. But anyone who loves movies or film criticism is biased toward Ebert and this film. He articulated the purpose of film better than anyone when he said that cinema is “a machine that generates empathy.” He is the face of film criticism. He shaped and informed an incalculable number of opinions on film, and through the experience of reading his reviews, his readers have formed an undeniable bond. That bond with Roger Ebert becomes entrenched through James’ doc, and the ache of his absence is deeply felt.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review