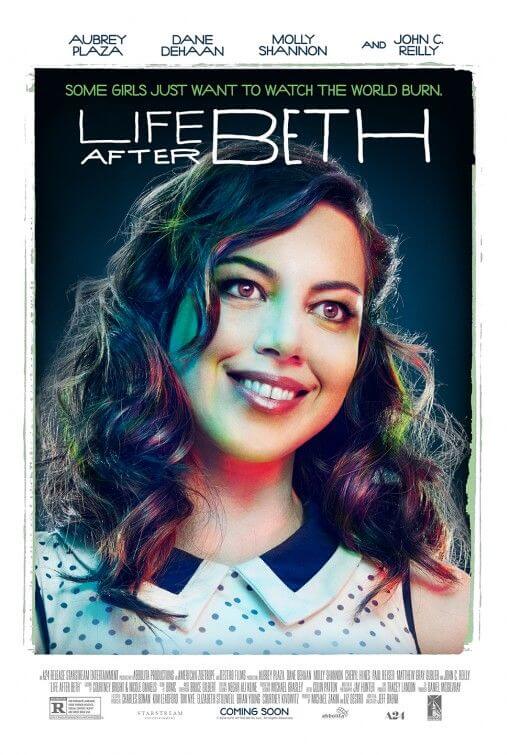

Life After Beth

By Brian Eggert |

Our society’s pop-culture obsession with zombies continues with Life After Beth, another entry in the sub-subgenre where a human carries on a romantic relationship with one of the living dead. There’s something inherently disgusting and unbelievable about this scenario that makes horror-comedy fans want to mine it for laughs, although it’s rarely accomplished with a satisfying outcome. Warm Bodies suggested that a young woman might fall for a zombie whose humanity slowly comes back as his love blooms around her; but the actionized, takes-itself-seriously third act of that film spoiled any hope for a believable romance. Fortunately, Fido went for a full-on satire, set in a 1950s world where post-apocalyptic zombies are used as pets and servants in Americana homes; the result was a fully formed absurdist romance between Billy Connoly’s brain-eater and Carrie-Ann Moss’ lonely suburban housewife.

Writer-director Jeff Baena’s Life After Beth is marginally more effective than Warm Bodies because it focuses on the zombie-human relationship and keeps the larger apocalyptic details as background noise. Still, the film doesn’t establish a firm set of absurdist rules; instead, there’s a hint of realism that feels inappropriate to this kind of story. Dane DeHaan plays Zach, who’s beset by grief at the loss of his girlfriend Beth (Aubrey Plaza). She was going to break up with him before she died of a snakebite while hiking, but he still loves her, to a fault. His parents (Paul Reiser, Cheryl Hines) are none too sympathetic about his loss, and so he takes some comfort from spending time with Beth’s parents, Maury (John C. Reilly) and Geenie (Molly Shannon). But when Beth’s parents suddenly won’t see him anymore, Zach starts snooping and sees Beth, seemingly alive and well, in their house.

Turns out Beth dug herself up one evening and appeared on their doorstep, and to keep suspicions down and onlookers away, her parents have resolved to keep her return a secret. Baena puts his own spin on the zombie rulebook here. After coming back to life, Beth looks relatively normal, talks without grunting or moaning (at first, anyway), her completion is lifelike, and her personality is retained despite some memory loss. Conveniently, she’s forgotten about wanting to break up with Zach; however, she’s plagued by some of Baena’s stranger additions to zombie mythology. Easy-listening smooth jazz soothes her sudden violent outbursts; she’s compelled to gather dirt and plaster it on the walls in the attic, where her parents are keeping her; and she’s convinced that she has to study for a test tomorrow (it’s always tomorrow, no matter how many days pass). Hilariously, human flesh isn’t on her mind at first. But Zach, who’s familiar with zombie mythology, keeps a paranoid eye on her hunger and remains fearful of becoming dinner.

While Zach wants to rekindle his relationship with Beth, her parents demand secrecy, and Baena’s overlapping, argumentative dialogue shines in these scenes and reminds us of the screwball situations from I Heart Huckabees, which Baena co-wrote with David O. Russell. But slowly, Beth’s behavior gets weirder, more like a traditional zombie, and Zach’s love for her is less a motivation than his fear of being eaten. Enter Erica (Anna Kendrick), Zach’s ditzy childhood friend who’s certain to become his rebound. When zombified Beth confronts the two, DeHaan is wonderfully awkward. He carries the movie’s emotional heft and makes a believable sad sack, while Plaza has fun in the early scenes of the disconnected Beth, but later on, she forces grunts that sound more like demonic possession. Of the supporting cast, Reilly and Shannon add the most to their traumatized, somewhat demented grieving parent roles.

Life After Beth drags on and becomes trying in the third act, when a larger zombie apocalypse takes hold of Zach’s hometown and other long-dead friends and relatives begin returning from the grave. How are these corpses not more decayed? Why are they coming back at all? It’s best not to ask too many questions when your protagonist doesn’t mind kissing, much less making love to, a resurrected (“Like Jesus,” Zach points out) corpse. Of course, in the long tradition of zombie metaphors, the whole movie stands as an allegory for dealing with the heartache of loss, be it the loss of life, or simply a bad breakup where the other party seems to become a raging monster afterward. Though not without its fair share of charms and laughs, the central notion of zombie physical romance is handled in an unbelievable way. Then again, perhaps ” unbelievable” is a poor argument against a movie where the dead return to life.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review