Life

By Brian Eggert |

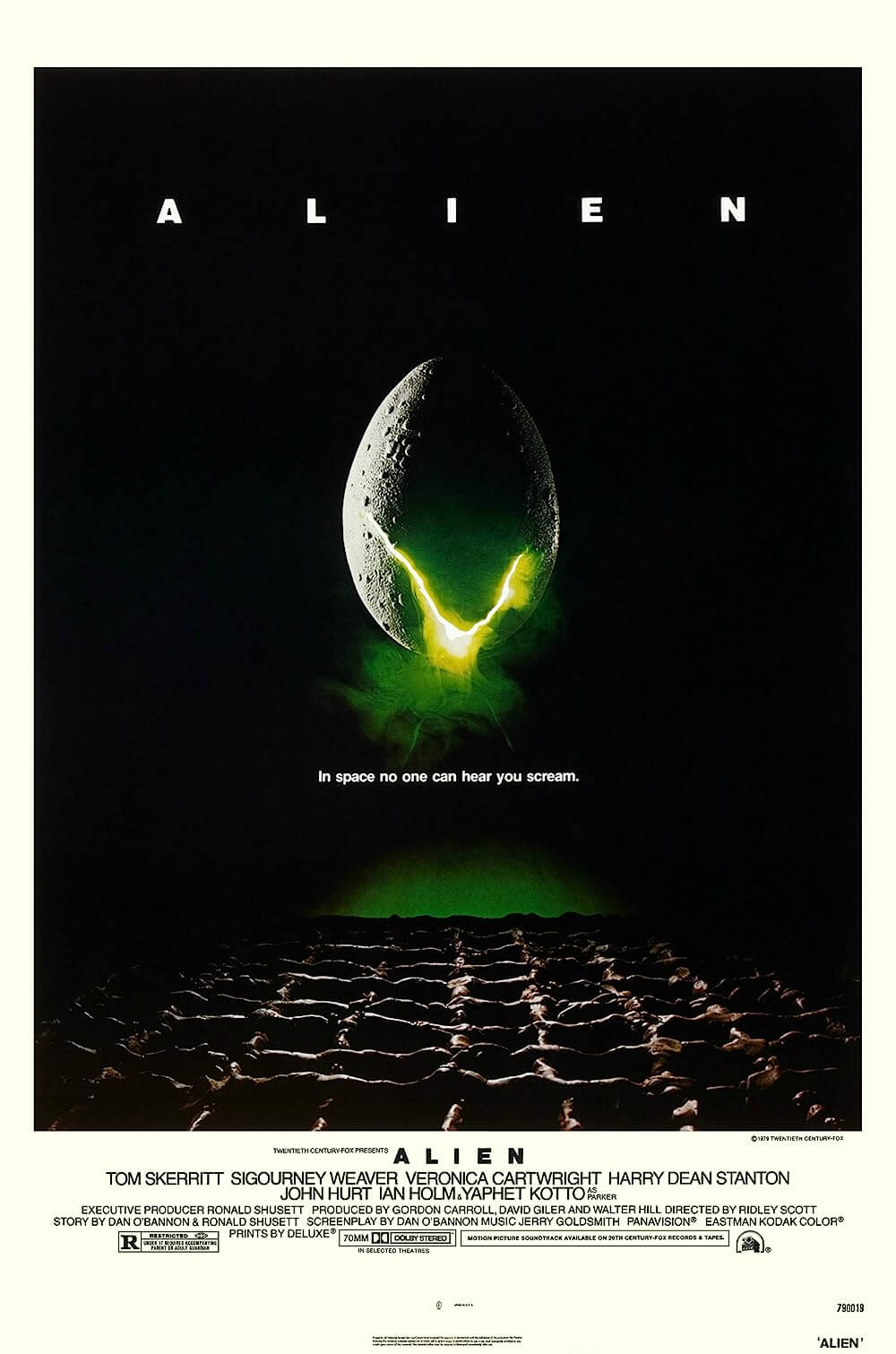

Imagine if Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien didn’t take place in isolation light years from Earth and didn’t capture the vast solitude of space. Now imagine the film without its blue-collar astronauts, each performed with an ensemble of eclectic actors capable of exuding incredible humanity; instead, the cast is comprised of marquee names. How would the film be if, in place of its vague hints of the alien lifeform in shadows and corridors, it boasted “alien vision” scenes to show a computer-animated creature perspective? And what’s more, instead of the terrifying physicality of practical monster effects that bring H.R. Giger’s frightening designs to life, the alien threat looked like a bland CGI blob. If you’re thinking this hypothetical scenario has removed everything that elevated Alien above the limitations of its genre, you would be correct. Now consider Life, in which all these details are realized.

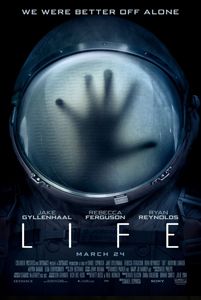

Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick were called “the real heroes” for writing Deadpool, and before that Zombieland. Needless to say, they have an affinity for self-aware genre fiction. Their script for Life combines several elements from other, better films and assembles them into a product devoid of substance or even a unique angle. Of course, a horror film set in space that borrows from titles such as Alien, The Thing, and Apollo 13 could not have picked better sources of inspiration. But Reese and Wernick’s alien-loose-on-a-spaceship programmer hits every required beat for this type of story, offering few variations or inspired flourishes along the way. What it boasts are some recognizable names (Jake Gyllenhaal, Ryan Reynolds) and expensive looking special FX. Also, perhaps unintentionally, its tagline “we were better off alone” suggests a pro-isolationist view that remains all too prevalent in today’s political climate, even in science-fiction after last year’s Arrival.

Life takes place in a NASA space station orbiting Earth, where a small team of scientists examines the first soil samples from a Mars probe. Their analysis leads to the discovery of a dormant, single-celled organism, the first proof of life on Mars (cue David Bowie). Inevitably, its dormancy evolves into an octopus-thing with a taste for (what else?) human blood. As the crew scrambles to maintain quarantine procedures and close air-tight hatches, their numbers dwindle. The ever-growing creature—dubbed “Calvin,” after an elementary school that apparently won a name-that-alien contest—proves alarmingly intelligent and resilient, soon evolving into a winged cephalopod with a face. Scenes in which Calvin behaves eerily smart are frantic and tense, although soon the limits of its killing-machine behavior become evident. Before long, the characters realize that fighting Calvin means a choice between exposing Earth to a Martian super-predator or sacrificing their lives to stop this thing.

Though Life has the budget and stars of an A picture, it behaves as though it’s in denial of its true B-movie functions. Director-for-hire Daniel Espinosa (Safe House) seems to think he’s helming the next Gravity or The Martian. His cinematographer Seamus McGarvey shoots in long, unbroken takes and tips the frame upside-down occasionally to remind us that concepts of up and down do not exist in space. Reese and Wernick’s script contains rudimentary scientific jargon, but nothing anyone mildly versed in the genre’s usual technobabble won’t recognize. Their treatment remains notable for attempting a surprise death on par with John Hurt’s demise in Alien, and then later a terrific conclusion that Rod Serling might have imagined. Even so, Life contains none of the social commentary or thoughtfulness of The Twilight Zone, and none of the visual style that might otherwise set it apart.

Whenever a horrific encounter with an alien lifeform occurs in a film, the humanity onscreen provides a necessary emotional investment and makes the proceedings worth watching. Rebecca Ferguson, Hiroyuki Sanada, Ariyon Bakare, and Olga Dihovichnaya serve in thankless supporting roles, while Gyllenhaal and Reynolds have only their onscreen persona to define their characters. Life relies on fast-paced plotting and a familiar killer alien setup, as opposed to making use of its actors or developing complex, dramatic circumstances. Similarly, the script fails to make the astronauts smarter than the audience; characters never “science the shit” out of their predicament or out-think the viewer. Aside from a few nerve-racking moments and, generally, professional production values, the film’s derivative quality and deficient innovations create a run-of-the-mill outcome that, ironically enough, may have been more fun and successful in less commercially viable hands.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review