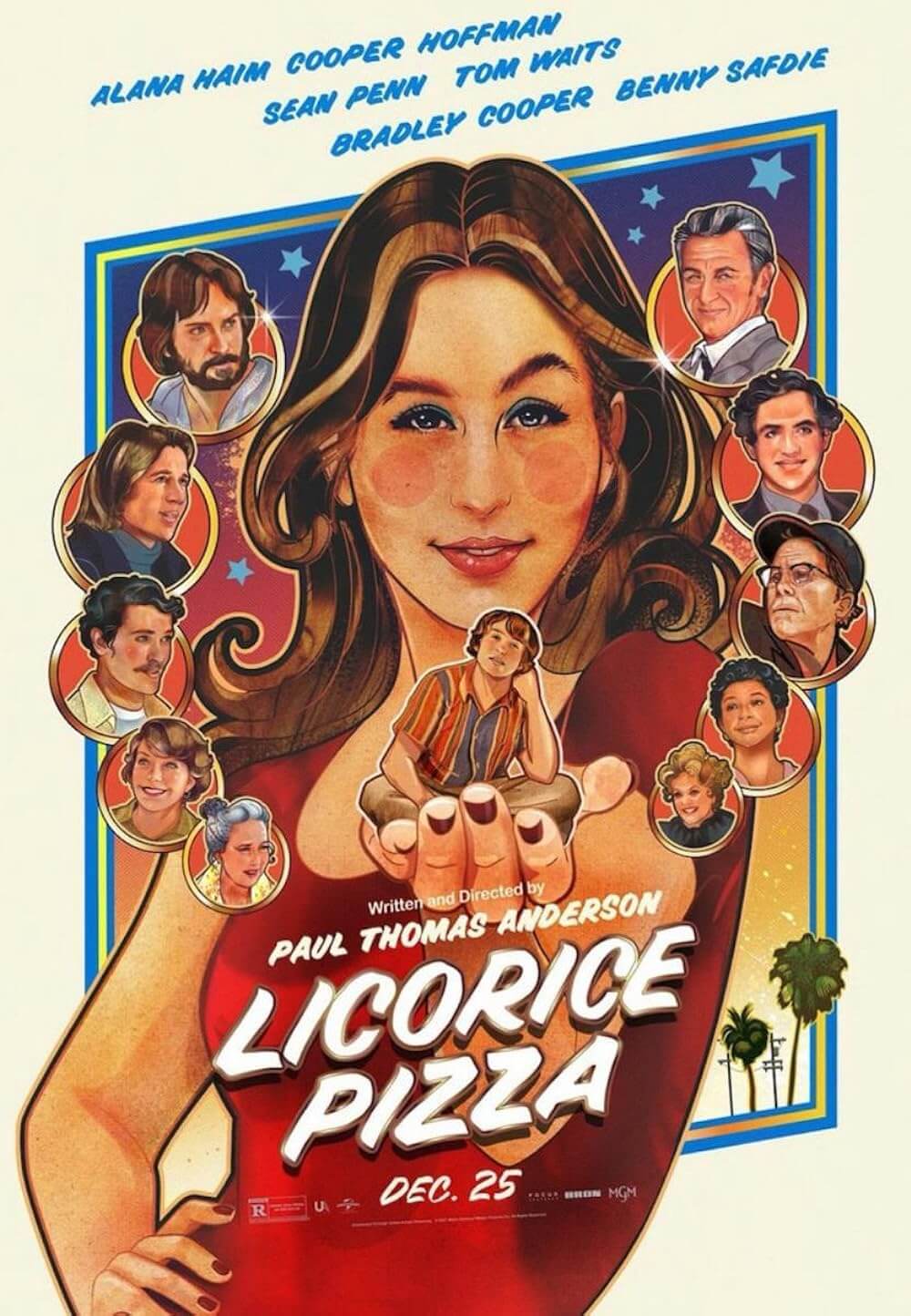

Licorice Pizza

By Brian Eggert |

There’s no such thing as a bad pizza. Whether it’s a wood-fired confection baked at 900 degrees or a cheap frozen helping consumed at midnight, every pizza offers some degree of pleasure. But, even if it’s imperfect, there’s something that makes the experience satisfying. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza has the appeal of every pizza ever sampled. Episodic in structure, the film is a picaresque of teenage ambition and folly, embarrassments and awkwardness, self-confidence and uncertainty, romantic hurdles and pursuant love. The meandering segments vary in appeal, but the overall effect resonates beyond the individual slices. Named after a SoCal record store chain from the 1970s, the film teems with needle drops and nostalgia, combined with another stellar score from Jonny Greenwood. Somehow, Licorice Pizza doesn’t feel like a film made in 2021 about another period; Anderson has created a film that looks and sounds like something that came straight out of 1973. It’s not a film about remembering when; it’s a film about living in that moment. Fortunately, it’s a moment that lasts two-and-a-half hours and zig-zags in every direction, leaving the viewer wrapped up in the sense that anything can happen.

The closest comparison might be Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), a clear source of inspiration for Anderson (the titular store even makes an appearance in the Ridgemont Mall). Just like that high-school comedy, Licorice Pizza is basically a coming-of-age story told over several months. Though it has an overall dramatic arc, it comprises tangents and subplots set in Anderson’s cherished San Fernando Valley. The film follows Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman, son of Philip Seymour Hoffman), a child actor based on Anderson’s friend Gary Goetzman. The name might not be familiar, but Goetzman became a Hollywood producer and collaborator with Jonathan Demme (The Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia) after a stint of acting in films such as Yours, Mine and Ours (1968). Not that such information will mean much to the average viewer. However, it serves as the launchpad for a story about a boy who grows out of acting and applies his resourcefulness to selling waterbeds at the Hollywood Palladium—inspired by something Goetzman did—among other entrepreneurialisms.

The young Hoffman makes his feature debut alongside another first-time performer, Alana Haim, best known as a band member of Haim alongside her sisters, Danielle and Este, who play Alana’s onscreen sisters (her actual mom and dad play her screen parents, too). Hoffman’s dad, of course, appeared in nearly every Anderson film from Hard Eight (1996) to The Master (2012). And there’s also George DiCaprio, father of Leo; Sasha and Destry Allyn Spielberg, daughters of Steven; and Dexter Demme, Jonathan’s nephew. Looking over the credits, it’s as though Anderson gathered friends and the children of friends to make a film about the small world in the Valley where everyone knows everyone else (or at least knows someone who does). Consider how Anderson was introduced to Haim not long after hearing one of their songs on the radio, only to discover later that their mother was his high-school art teacher. He went on to direct several of their music videos and supply album cover art. Behind the scenes, a touch of magic and coincidence colors how Anderson met the people involved and how he carries that over to the screen story.

Haim and Hoffman show an incredible amount of confidence and chemistry; both exude a movie-star quality, like they’ve been acting for years, and it now comes naturally. Their performances carefully walk around the tenuous romance at the center. Though, their characters spend most of the film out of sync. Gary first spies Alana at school. She works for a photographer (who casually slaps her on the ass on the job), and she can’t help notice Gary’s extraordinary self-assurance when he starts talking about how “our roads brought us here.” He’s like a more talented and put-together version of Max Fischer from Rushmore (1998), capable of juggling a half-dozen projects while his parents work. Besides his own PR company, he has a list of acting credits, and a name people in the entertainment business recognize. “I’m a showman,” he tells her. “I don’t know how to do anything else.” He’s also 15 years old. She’s 25, or maybe older, and she’s floundering about her future. Gary asks her to dinner at his favorite restaurant, the darkly lit nightspot, Tail o’ the Cock. And for reasons she never articulates, she shows up.

From there, Alana and Gary orbit around each other. Alana agrees to be his chaperone on an acting gig in New York. She can’t help but feel drawn to Gary’s charismatic energy, but she’s also aware that he’s wildly inappropriate for her. Yet, as a struggling adult who still lives at home, she longs for the freedom and relative certainty of teendom—a vantage point from which the whole world is full of possibility. Plus, Gary makes her feel oddly confident in her own skin by working alongside her at his waterbed company, where she becomes his successful “business partner” and pointedly not his “lady friend.” He helps her audition for acting roles, including a role opposite a William Holden-style actor (Sean Penn) in what would become Breezy (1973). They navigate the 1970s oil crisis, leading to an encounter with hairdresser and producer Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper), the rampant ladies man who’s quick to remind people that he’s dating Barbra Streisand. There’s some death-defying business involving a sabotaged waterbed and an out-of-gas truck that proves hair-raising. However, Peters is a source of danger—he threatens Gary and practically forces himself on Alana. Later, she works for Joel Wachs (Bennie Safdie), a closeted politician in an intolerant community. But then, she inexplicably finds herself drawn to Gary’s latest venture—newly legalized pinball machines. All of these other men treat Alana like an accessory. Only Gary considers her a partner.

Anderson carries the audience through these chapters with a light touch so that, despite the eventful segments (featuring appearances by Tom Waits, Maya Rudolph, Christine Ebersole, Skyler Gisondo, and Joseph Cross), the focus remains on Alana and Gary. She feels unsure about her friendship with Gary. When he flirts with a girl his age, she’s embarrassed about her jealous reaction (especially after she hits him with a cheap insult, “I’m cooler than you”). If she goes on a date or agrees to take her shirt off for an acting role, Gary becomes overprotective. To be sure, there’s a baseline immaturity at work between them. Gary’s teenage boy sensibilities (he has a penchant for jokes only a boy would find funny) keep reminding Alana of his age, regardless of his curious maturity in matters of business and selfhood. The drifting Alana doesn’t have all his qualities, and her status as a young woman in this setting places her in thorny situations. If Cooper and Penn’s characters would quickly exploit her, Gary feels genuine affection for Alana and restrains his worst, horny-boy impulses with her. Somehow, his maturity and her immaturity make an appropriate pairing. They’re going in different directions, captured in long shots of Gary running this way or Alana running that way. But they’ll end up together, eventually, in a way that’s as messy and strangely romantic as their feature-long courtship.

The moralist 2021 viewer might feel their antennae ping with caution a few times during Licorice Pizza. Should audiences be so quick as to celebrate a film centered on the burgeoning relationship between a 15-year-old boy and a 25-year-old woman? And should we feel their overwhelming sense of requited love when Gary and Alana finally embrace in the end, anticipating the next several years of their illegal relationship before Gary comes of age? Much has been made about the age difference in the media. Just as much has been written about the white restaurateur (John Michael Higgins) who talks to his Japanese wives in a groan-inducing accent. But Anderson isn’t the type of filmmaker to wag his finger at the reality of 1970s America, and he avoids judging his characters from a contemporary (and self-righteous) viewpoint. Representation isn’t an endorsement of a worldview, as the disclaimer goes. While the film portrays some behavior that today would be ill-advised, he’s showing a time when significant age gaps in relationships were not uncommon, and people often married in their teens. Anderson’s cinema has always been about accepting his characters for who they are in their environment, and Licorice Pizza is no different.

Shooting the film alongside cinematographer Michael Bauman, Anderson crafts a film that looks and feels like a product of its time, in a way that’s infrequently captured anymore. Anderson and Bauman shot on 35mm, a rare thing in Hollywood today, on lenses once used by legend Gordon Willis—who shot The Godfather trilogy and some of Woody Allen’s best work. Anderson and Bauman’s yellowy images radiate from the spotlight outside of Gary’s store to the beams illuminating dust in the afternoon, suggesting an old photo or a memory—or perhaps just the films of Hal Ashby. Although Anderson has shot in this period before with Boogie Nights (1997), his caricature of the adult film industry, that film played like an ironic if surprisingly human evocation of a time and place. With stunning work from production designer Florencia Martin and costume designer Mark Bridges, Licorice Pizza feels like a selfless immersion by a filmmaker who has matured since the days of Dirk Diggler.

For all his knocking around and scheming, Gary has an infectious energy that best serves to highlight what makes Alana so unique, so full of potential, so volatile, yet also so lost. She’s the kind of classic movie character that people will fall in love with. Licorice Pizza pulls the viewer along as these two circle each other, on again and off again, wandering through their series of misadventures. And while achingly romantic, the film also embraces the unpredictable era in which these characters meet—the scenes of an odd loner stalking Wachs never entirely give the audience closure, unnervingly so. And there’s Gary’s random arrest after cops misidentify him as a teenage murderer: The police haul him away, and Alana chases after. She sprints to the police station and sees Gary uncuffed after a witness clears him. Alana urges him to join her outside, and they share the truest hug imaginable before escaping and running together with laughter. The whole film feels as unselfconscious and personal as this blithe escape. It’s a rare kind of experience that brings joy and affection through its breezy, expansive, and honest world. Through all of its brilliant craftsmanship, open performances, and exhilarating emotional effect, Licorice Pizza is also the director’s most warm-hearted and tender film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review