Leviathan

By David Hill |

In the West, much of the reception of Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s 2014 masterpiece Leviathan has focused on the film’s critique of Vladimir Putin’s Russia and on the comments made by Vladimir Medinsky, Russia’s Minister of Culture at the time of the film’s release. Medinsky stated that he did not like the film, and he criticized Zvyagintsev for allegedly depicting Russians in a negative fashion. Leviathan does indeed contain a few swipes towards Putin’s Russia. In a much-discussed scene, portraits of former Soviet leaders from Lenin to Gorbachev are used as rifle targets. When the character who brought the portraits is asked whether he has anyone more current, he answers that it is too early to use portraits of the current leaders as they should first “ripen up on the wall a bit.” All the while, a portrait of Putin hangs prominently on the wall of a corrupt politician’s office.

However, it would not do Leviathan justice to put too much emphasis on these aspects. The film is much more than a critique of Putin’s Russia; it contains universal truths about human nature and power structures that are not limited to a specific time and place. Furthermore, the Western media’s coverage of the negative reaction from Russian officials must be described as exaggerated. While it is true that Medinsky and other Russian officials were critical of the film, and that the film had a bumpy road to its theatrical release in Russia (with Zvyagintsev having to re-edit the dialogue in order to comply with a new Russian law against swearing in films), it should be noted that Medinsky still acknowledged the quality of the film and that Russia still chose it as the country’s official submission for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film (Leviathan ended up being nominated, but it lost out to Pawel Pawlikowski’s Ida). In addition to that, approximately 35 percent of the film’s budget was provided by the Russian state.

Leviathan tells the story of Kolya (Aleksey Serebryakov), a car mechanic who lives in an idyllic house on the coast of the Barents Sea with his wife, Lilya (Elena Lyadova, who also starred in Zvyagintsev’s previous film Elena), and his son from a previous marriage, Romka (Sergey Pokhodaev). When Vadim (Roman Madyanov), the corrupt local mayor, tries to expropriate the land on which Kolya’s house is built and only offers a ridiculously low sum as compensation, Kolya enlists the help of his friend Dima (Vladimir Vdovichenkov), with whom he had served in the army and who is now a hotshot lawyer in Moscow. Things quickly spiral out of control when Dima not only tries to blackmail Vadim after realizing that challenging the latter’s plans through the official channels is a lost cause given the omnipresent corruption, but he also starts (or perhaps continues–the film is ambiguous in that regard) an affair with Lilya that doesn’t go unnoticed by Kolya.

Even though the film contains various Russia-specific elements (including heavy vodka drinking that borders on cliché), Zvyagintsev’s idea for Leviathan did not have its origin in Russia, but rather in the USA. In 2004, American muffler shop owner Marvin Heemeyer went on a rampage in Granby, Colorado, after a year-long feud with the town’s officials regarding the construction of a concrete plant that blocked access to his shop. After losing an appeal and being fined for various violations, Heemeyer demolished several buildings in Granby (including the town hall and the former mayor’s house) with a bulldozer that he had modified by adding layers of steel and concrete as armor. Heemeyer’s rampage lasted for more than two hours as the authorities were not able to stop the modified bulldozer (later dubbed “Killdozer” by the media). The incident ended with Heeymeyer committing suicide. Zvyagintsev heard about this when he was in the USA in 2008 to shoot Apocrypha, a short film featuring Carla Gugino that was supposed to be a segment of the anthology film New York, I Love You, but was ultimately cut.

Zvyagintsev, fascinated by Heemeyer’s story, was inspired to write the screenplay for Leviathan with his co-writer Oleg Negin (with whom he had already written his previous film, Elena). Their initial plan was to set the film in the USA and to closely adhere to Heemeyer’s story. However, the more they worked on the screenplay, the more they moved away from that idea. They ultimately decided to set the film in Russia and to change the ending as they felt Heemeyer’s rampage did not fit the Russian temperament. Furthermore, they started to incorporate other influences, most notably the Bible’s Book of Job. The film borrows its title from the Book of Job in which a powerful sea beast called Leviathan is referenced, and there are various parallels between the long-suffering Job and the film’s main character Kolya. Film critic Peter Travers even called Leviathan a contemporary remake of the Book of Job in his review of the film.

Other important influences were Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, the 1651 book by English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, and Michael Kohlhaas, the 1808 novella by German author Heinrich von Kleist. Hobbes’ socio-philosophical book is about the structure of society and the state. He argues for an all-powerful state with a strong and undivided government (in other words, the state should be as strong as the sea beast Leviathan according to Hobbes, hence the title of his book). As will be described in more detail below, the state has a similar role in the film Leviathan, but Zvyagintsev, unlike Hobbes, is critical of such a powerful state. Given these parallels between the film and Hobbes’ book, it is surprising that Zvyagintsev did not know about the book when he started working on the film. He only became aware of it when a friend asked him whether his next feature called Leviathan would be an adaptation of Hobbes’ book.

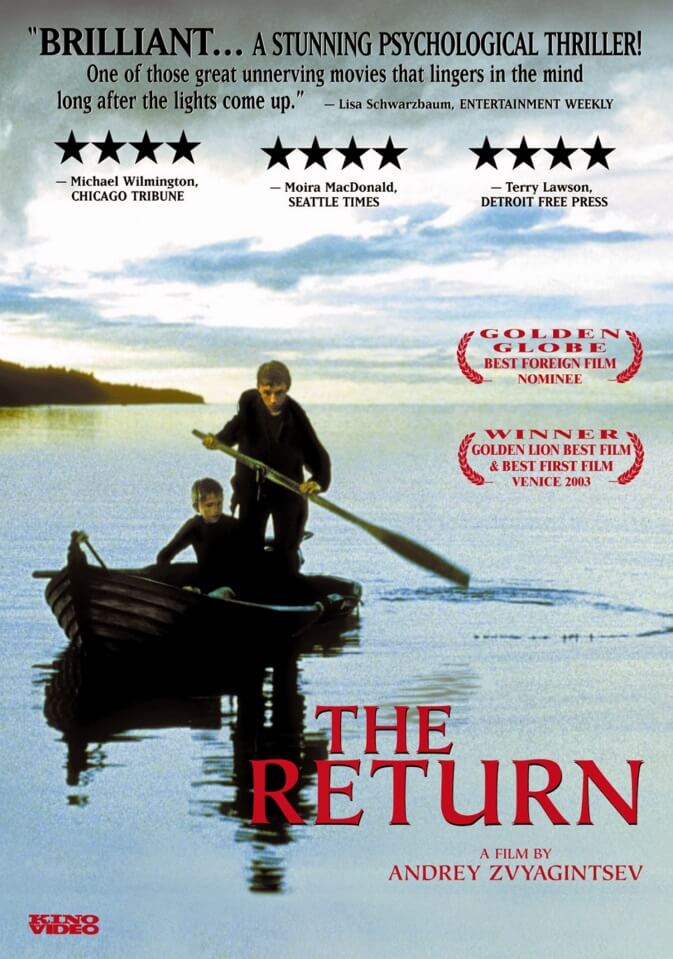

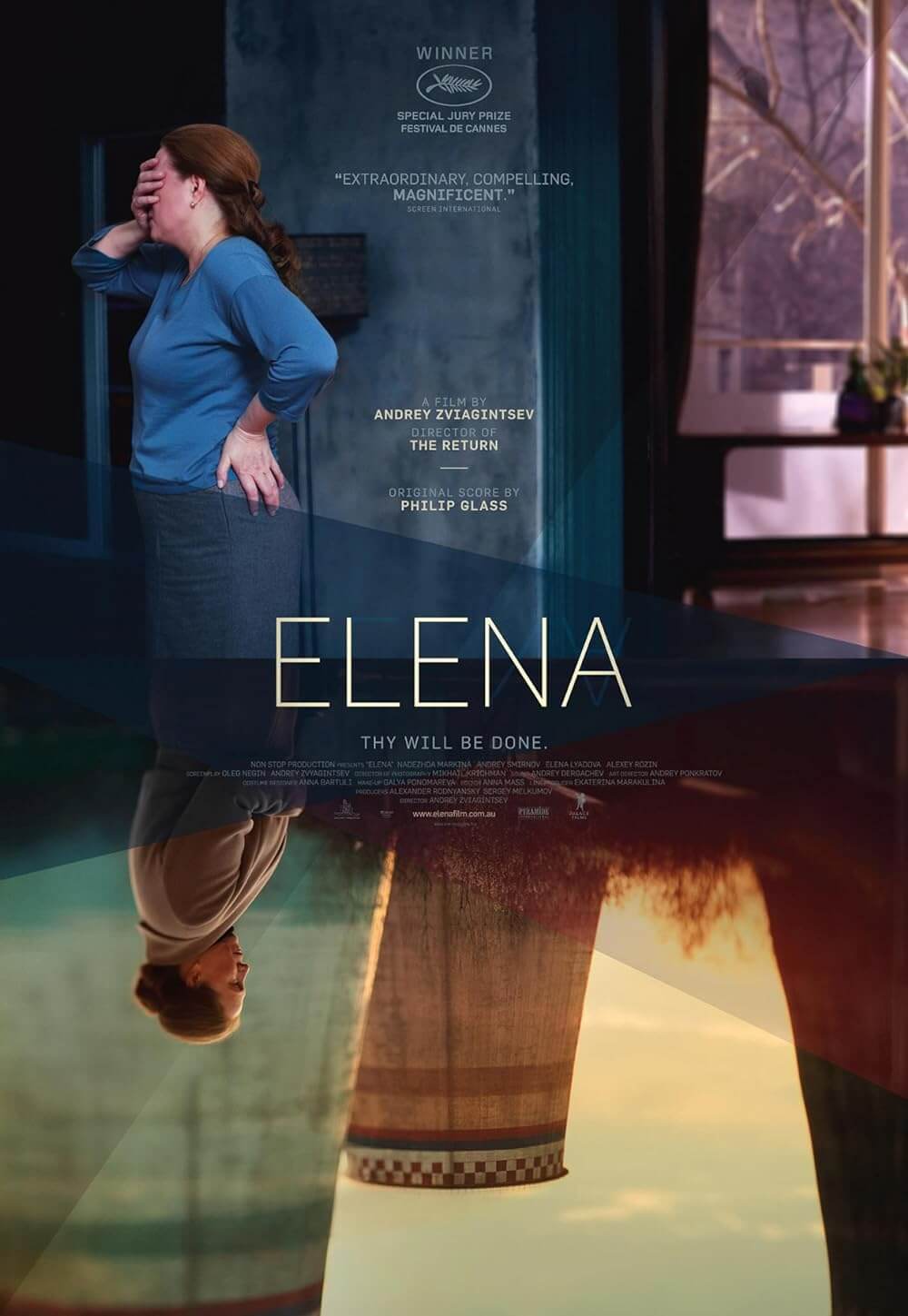

Before Zvyagintsev made Leviathan, he had directed three features. His first two films, The Return and The Banishment, were rather similar. They mainly worked on a metaphorical level and had an abstract feel to them, not least due to several symbolic landscape shots. This gave them an intriguing and unique atmosphere, but it also made them somewhat difficult to decipher and to emotionally engage with (especially in the case of The Banishment). On the other hand, Zvyagintsev’s third feature, Elena, was more grounded and specific, which made for a more emotionally engaging viewing experience. It did however lack the mythical dimension and epic scale of the director’s first two features, even though it still had plenty to offer beyond its surface. With Leviathan, Zvyagintsev was able to successfully combine the abstract and mythical elements of The Return and The Banishment with the more concrete and emotionally engaging elements of Elena.

Leviathan opens and closes with majestic landscape shots that are accompanied by epic music from the prelude to Philip Glass’ 1983 opera, Akhnaten. These shots hint at the film’s allegorical nature, and they add weight to Kolya’s struggles. The film can indeed be read as a universal story about a little man being crushed by an authoritarian and corrupt state, whereas Vadim can be seen as a personification of said state. This explains why he is less fleshed out than the film’s other characters and feels like a caricature at times. Through this reading of the film, Vadim, representing the state, can be seen as the beast referred to by the film’s title.

Leviathan opens and closes with majestic landscape shots that are accompanied by epic music from the prelude to Philip Glass’ 1983 opera, Akhnaten. These shots hint at the film’s allegorical nature, and they add weight to Kolya’s struggles. The film can indeed be read as a universal story about a little man being crushed by an authoritarian and corrupt state, whereas Vadim can be seen as a personification of said state. This explains why he is less fleshed out than the film’s other characters and feels like a caricature at times. Through this reading of the film, Vadim, representing the state, can be seen as the beast referred to by the film’s title.

However, the figurative beast that crushes Kolya does not only consist of the state but also of the church. Zvyagintsev adds another layer to Leviathan by showing Vadim in alliance with a local Russian Orthodox Church bishop (Valeriy Grishko). The bishop is a shady and spiritually corrupt figure who is surrounded by luxury, and he encourages Vadim to use his power and to apply illegitimate measures to deal with Dima’s attempt at blackmailing him. The true nature of the bishop’s motivations for being in alliance with Vadim are not made explicitly clear until a poignant epilogue. Suffice it to say that his motivations are neither spiritual nor noble, and that his character can be read as a larger critique of the church.

Religion and faith have always played an important role in Zvyagintsev’s films, but Leviathan marked the first time that he made a clear distinction between religion and church. Zvyagintsev seems to argue that spirituality and faith are important, but that they cannot necessarily be found in the church (especially if the church is run by immoral bishops who are in alliance with corrupt politicians). This point is emphasized by a subtle reference to Pussy Riot (a Russian punk rock band most well-known for its controversial “punk prayer” performance in a Moscow church in 2012) and by a pious and humble priest (Vyacheslav Gonchar), whom Kolya meets towards the end of the film. The priest is a minor but important character of Leviathan. Not only is he the exact opposite of the bishop and an example of a true man of God, but he also makes the above-mentioned parallels between Kolya and Job explicit by telling Kolya about Job’s struggles.

In addition to having a rich and fascinating subtext, Leviathan also works on a pure surface level. It is Zvyagintsev’s most accessible and emotionally engaging film to date, and it contains a surprising amount of humor despite its bleak subject matter. Take the tragicomic and poignant early scene where a judge, who is later revealed to be an accomplice of Vadim, reads out a verdict as if she were a robot incapable of human emotions. Nevertheless, Leviathan is far from being popcorn entertainment, and the film is in line with the director’s previous work despite its increased accessibility. In particular, Zvyagintsev once again leaves many things open to interpretation (several key plot points are not shown on screen), and the film requires some degree of patience from its viewers (not least because of its length of almost two-and-a-half hours). However, viewers who are willing to invest their time and attention in Leviathan will find the film to be incredibly rewarding–both intellectually and emotionally.

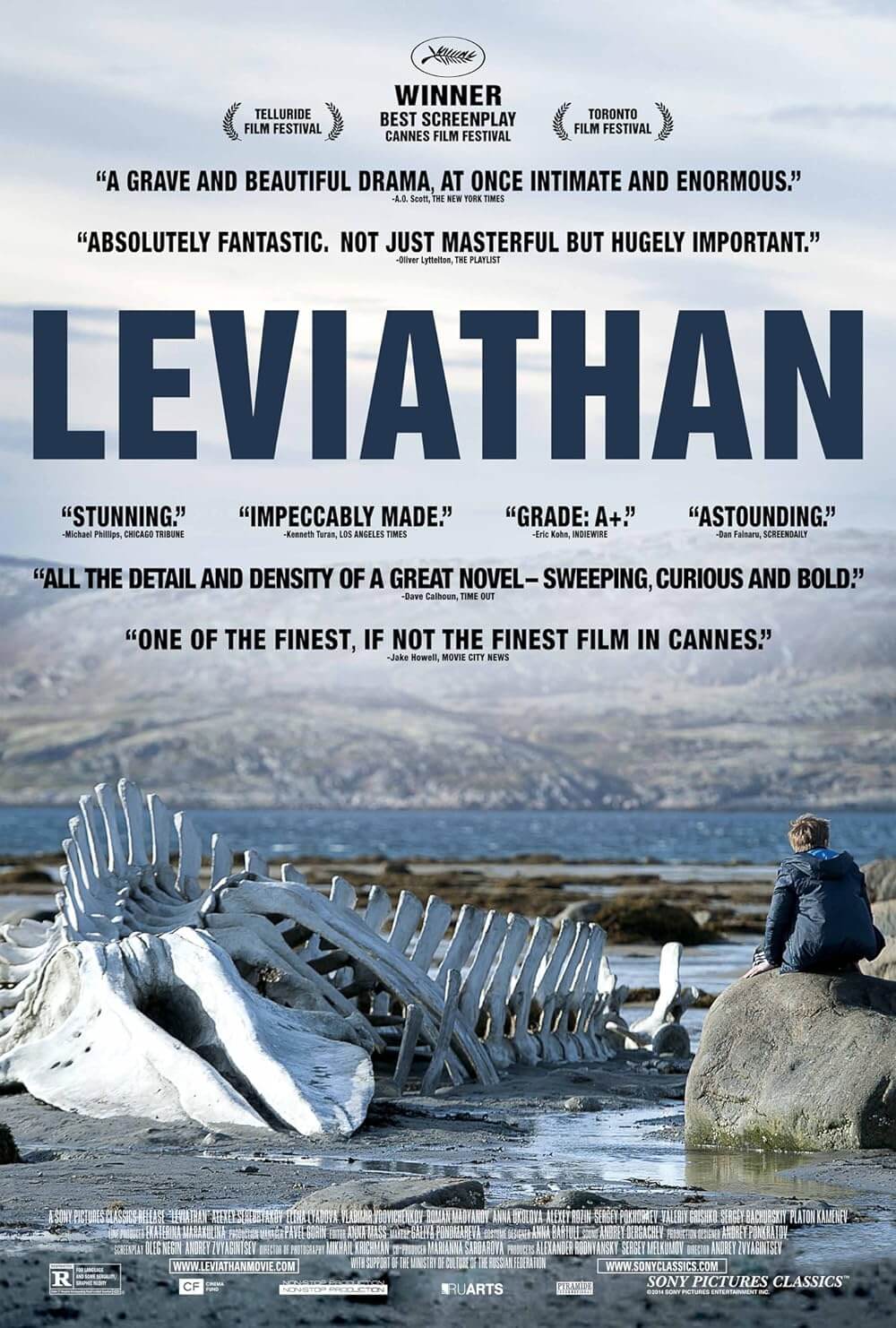

As one expects from a Zvyagintsev feature, Leviathan’s technical elements are flawless. In particular, this applies to the cinematography by his regular collaborator Mikhail Krichman. Once again, the film was shot on 35mm and contains a muted color palette that is mostly made up of blues and greys. Krichman’s cinematography has been outstanding in each of Zvyagintsev’s films, but he truly outdid himself on Leviathan. Apart from the above-mentioned landscape shots that are nothing short of spectacular, there are two shots containing sea beast imagery that deserve to be highlighted: Firstly, there is the iconic image of Romka sitting next to the skeleton of a blue whale that is featured on the film’s poster (the skeleton seen in the film was not a real skeleton, but rather a prop made out of metal, wood, and polystyrene); secondly, there is a striking appearance of a living blue whale towards the end of the film shortly before a crucial and tragic plot turn occurs.

As one expects from a Zvyagintsev feature, Leviathan’s technical elements are flawless. In particular, this applies to the cinematography by his regular collaborator Mikhail Krichman. Once again, the film was shot on 35mm and contains a muted color palette that is mostly made up of blues and greys. Krichman’s cinematography has been outstanding in each of Zvyagintsev’s films, but he truly outdid himself on Leviathan. Apart from the above-mentioned landscape shots that are nothing short of spectacular, there are two shots containing sea beast imagery that deserve to be highlighted: Firstly, there is the iconic image of Romka sitting next to the skeleton of a blue whale that is featured on the film’s poster (the skeleton seen in the film was not a real skeleton, but rather a prop made out of metal, wood, and polystyrene); secondly, there is a striking appearance of a living blue whale towards the end of the film shortly before a crucial and tragic plot turn occurs.

The acting in Leviathan deserves special praise as well. The film features Zvyagintsev’s largest cast to date, and all actors give great performances (especially Aleksey Serebryakov as Kolya and Elena Lyadova as Lilya). Thanks to the actors and the film’s exquisite screenplay, almost all the film’s characters feel like real people who are made of flesh and blood and who have both flaws and redeeming qualities. This makes them relatable, and it is one of the reasons for the film’s increased accessibility and emotional impact compared to Zvyagintsev’s earlier films. Most of the film’s actors were not well-known in the West before Leviathan came out, but many of them were already popular in Russia. As film scholar Julian Graffy points out, Zvyagintsev carefully chose the actors according to their on-screen personalities to create a dialogue with other films. Take Vladimir Vdovichenkov, who plays Dima and who has often been cast as the cool and tough guy. In one of his most famous roles in the 2003 film The Bimmer, he played an apparently tough guy from Moscow who was then exposed as weak and ineffective when he ventured into the Russian countryside, which is similar to what happens to his character in Leviathan.

Leviathan is Zvyagintsev’s most ambitious and well-known film to date, and it is rightly heralded by many as his magnum opus. The film successfully combines different elements of the director’s previous films, in particular, the mythical and allegorical dimension of The Return and The Banishment, and the more specific and intimate aspects of Elena. This makes for an engaging viewing experience, and the film lingers on the viewer’s mind and invites examination of its rich subtext until long after the credits have rolled. It is therefore unsurprising that Leviathan was universally praised by critics and that it won a string of awards, most notably the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film, the Best Screenplay Award at the Cannes Film Festival, and the Best Feature Film Award at the Asia Pacific Screen Awards. The film is a masterpiece that cemented Zvyagintsev’s reputation as one of the best and most important contemporary directors in international cinema.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian. “Here Be Monsters.” Sight & Sound, Vol. 24, No. 12, December 2014, pp. 27-29.

Dolin, Anton, and Oleg Dubson. “In the Belly of the Beast.” Film Comment, Vol 50, No. 6, November/December 2014, pp. 42-47.

Hynes, Eric. “Leviathan: The World at Large.” Reverse Shot. 31 December 2014. http://www.reverseshot.org/reviews/entry/1980/leviathan/. Accessed 19 October 2020.

Gilbey, Ryan. “Leviathan.” Sight & Sound, Vol. 24, No. 12, December 2014, p. 77.

Graffy, Julian. “Andrei Zviagintsev: Leviathan.” KinoKultura. April 2015. http://www.kinokultura.com/2015/48r-leviafan.shtml. Accessed 19 October 2020.

Menashe, Louis. “Leviathan.” Cinéaste, Vol. 40, No. 1, Winter 2014, pp. 49-50.

Romney, Jonathan. “Film of the Week: Leviathan.” Film Comment. 31 December 2014. https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/film-of-the-week-leviathan-zvyagintsev-russia/. Accessed 19 October 2020.

Travers, Peter. “Leviathan.” Rolling Stone. 17 December 2014. https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-reviews/leviathan-255597/. Accessed 19 October 2020.

Vassilieva, Julia. “2014: Leviathan (Andrey Zvyagintsev).” Senses of Cinema. December 2017. http://sensesofcinema.com/2017/soviet-cinema/2014-leviathan-andrey-zvyagintsev/. Accessed 19 October 2020.

David Hill is a lawyer from Switzerland who currently works as a legal counsel for an insurance company. He has long had a passion for cinema, and he uses most of his spare time to watch and research films. His main interest focuses on arthouse films, and he occasionally makes contributions to Deep Focus Review as a guest writer.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review