Let Them All Talk

By Brian Eggert |

Let Them All Talk is director Steven Soderbergh’s answer to chatty French comedies. His cast members inhabit posh surroundings, eat expensive food, and discuss sophisticated topics, while their personal lives remain in shambles. At one point, someone refers to a “comedy of errors;” however, it has nothing in common with Shakespeare’s broad play of the same name nor the farcical mode of situation comedy. Though the cruise ship setting lends itself to humorous situations, as Monkey Business (1931) and The Lady Eve (1941) proved, Soderbergh’s approach is far more low-key and observational. Working from an outline and brief character descriptions supplied by short fiction writer Deborah Eisenberg, the director and his cast improvised scenes over an actual two-week crossing from New York to Southampton, England, aboard the Queen Mary 2. Enclosed in a formal, elegant setting, Soderbergh does as the title suggests, and then he shapes the result into a surprisingly cohesive, thematically rich experience.

Meryl Streep stars as Alice Hughes, an intellectual fiction writer set to receive an award in England, called the Footling Prize. She refuses to fly, and so her new literary agent, Karen (Gemma Chan), arranges for passage on the Queen Mary 2. Alice insists that her nephew, Tyler (Lucas Hedges), who also serves as her assistant, join her. She also asks along two friends from college, Susan (Dianne Wiest) and Roberta (Candice Bergen), in hopes of “reconnecting the gang of three we used to be.” Having won a Pulitzer for her book You Always You Never, Alice’s career as a distinguished author has overshadowed her friends: Susan helps imprisoned women prepare for their parole hearings; Roberta, who was the unofficial inspiration of Alice’s most famous novel, has fallen on hard times in part because of what Alice wrote about her. Though she invites them along seemingly to reconnect, Alice spends much of her time working on her secretive new novel, which Karen is desperate to learn more about for the publisher. Could it be a much-anticipated sequel to You Always You Never?

The character dynamics become essential to enjoying Let Them All Talk. Terrifically performed by the ensemble, Streep, Wiest, and Bergen’s interactions feel loaded with history. And since the substance of their conversations were largely improvisations drawn from Eisenberg’s brief backstories, it’s all the more impressive to behold. Each morning on the ship, Alice and Tyler wake to have breakfast, talk about the day’s schedule, and what happened the night before—and that was the actual breakfast shared by Streep and Hedges. Susan and Roberta wander the ship or play a board game like Scrabble or Monopoly, usually talking about Alice. “Did she always talk like that?” they ask, referring to Alice’s affected, self-serious manner. In their casual conversation, Susan reveals kernels about her wild, yet-undisclosed past. Roberta, who has a thankless job as a lingerie store clerk, admits her ulterior motives: she’s on a gold-digging mission, whether by landing some wealthy passenger or guilt-tripping Alice into compensation.

Elsewhere, Susan finds herself talking with best-selling mystery writer Kelvin Krantz (Dan Algrant), whose books (with titles like Boiling Point and Fugue State) Susan and Roberta find more accessible than their friend’s. Alice seems to resent Krantz’s status as “a one-man publishing industry,” She implies as much when she asks him how long it takes him to write one of his potboilers. “Four months,” she observes with patronizing surprise, “that’s longer than I thought.” Meanwhile, Tyler learns that Karen has secretly joined them on the ship, hoping to gather some intel on the subject of Alice’s new book. When she enlists Tyler to help, he misreads that as a sign of something more, and the result is equally heartbreaking and awkward. And then there’s the mysterious stranger (John Douglas Thompson) whom Alice spots by the pool reading The Odyssey, and whom Tyler spies coming out of Alice’s room in the morning. “That man is probably the one thing that keeps me going,” Alice later remarks in an all-too-true statement.

Elsewhere, Susan finds herself talking with best-selling mystery writer Kelvin Krantz (Dan Algrant), whose books (with titles like Boiling Point and Fugue State) Susan and Roberta find more accessible than their friend’s. Alice seems to resent Krantz’s status as “a one-man publishing industry,” She implies as much when she asks him how long it takes him to write one of his potboilers. “Four months,” she observes with patronizing surprise, “that’s longer than I thought.” Meanwhile, Tyler learns that Karen has secretly joined them on the ship, hoping to gather some intel on the subject of Alice’s new book. When she enlists Tyler to help, he misreads that as a sign of something more, and the result is equally heartbreaking and awkward. And then there’s the mysterious stranger (John Douglas Thompson) whom Alice spots by the pool reading The Odyssey, and whom Tyler spies coming out of Alice’s room in the morning. “That man is probably the one thing that keeps me going,” Alice later remarks in an all-too-true statement.

Still, there’s plenty of conversations in-between these larger dramatic strokes to savor. In particular, Tyler shows genuine interest in gaining the women’s perspective on how the world has changed, how they will be the last generation with pre-digital experience. Although Tyler sees a major paradigm shift between their generations, Susan argues, “Human communication is basically the same because humans are basically the same.” In other words, the notion that digitization creates a barrier for intimate interpersonal communication is a fallacy; after all, Susan and her pre-digital friends have no easier time communicating with each other with the gizmos at their disposal. Certainly, the digital world hasn’t helped bring them together, but there’s no sense in romanticizing a world before the internet and smartphones. Then again, perhaps there’s something to Susan’s observation about the night sky, and how we can no longer look up and feel assured that those are stars and not satellites launched by Elon Musk.

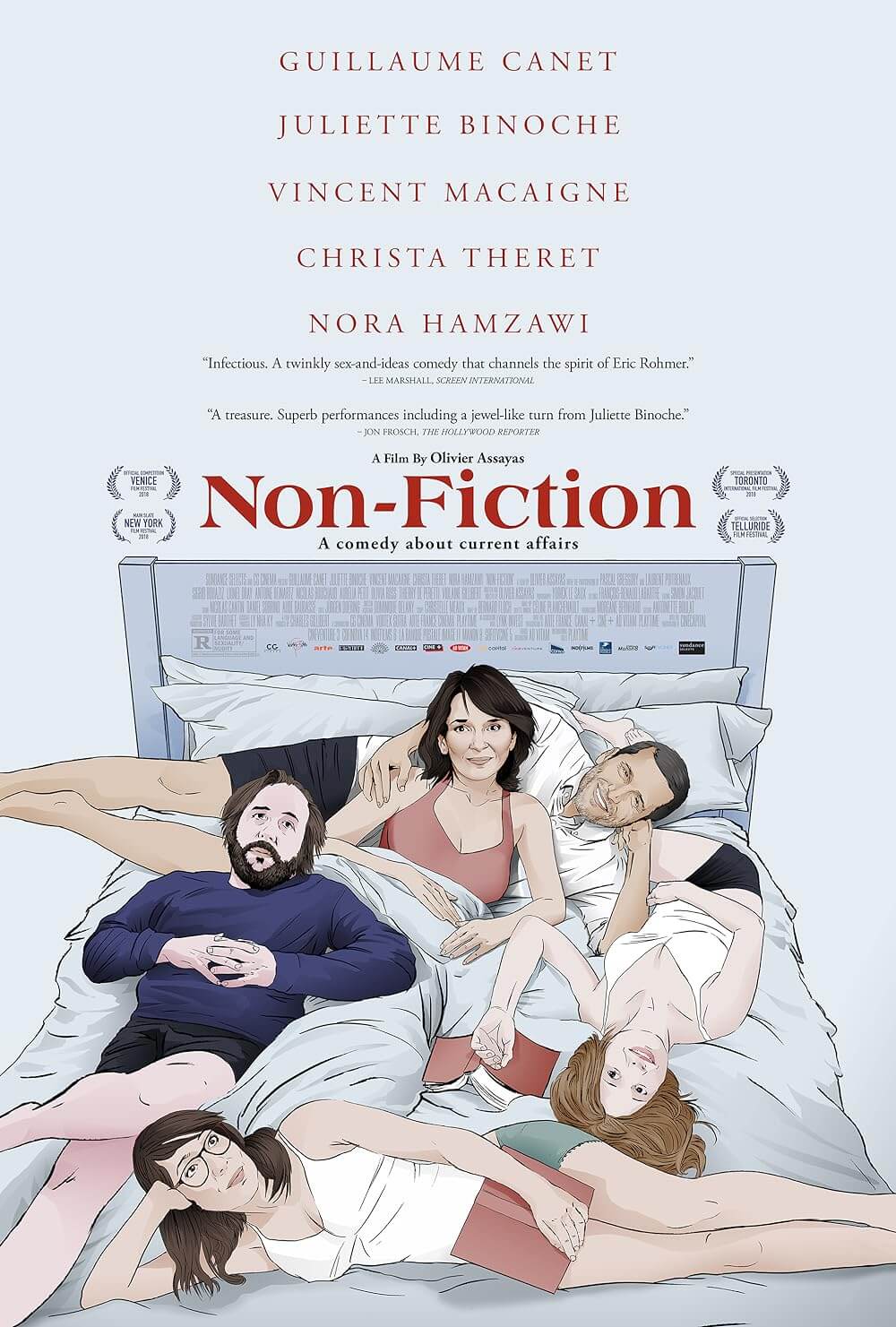

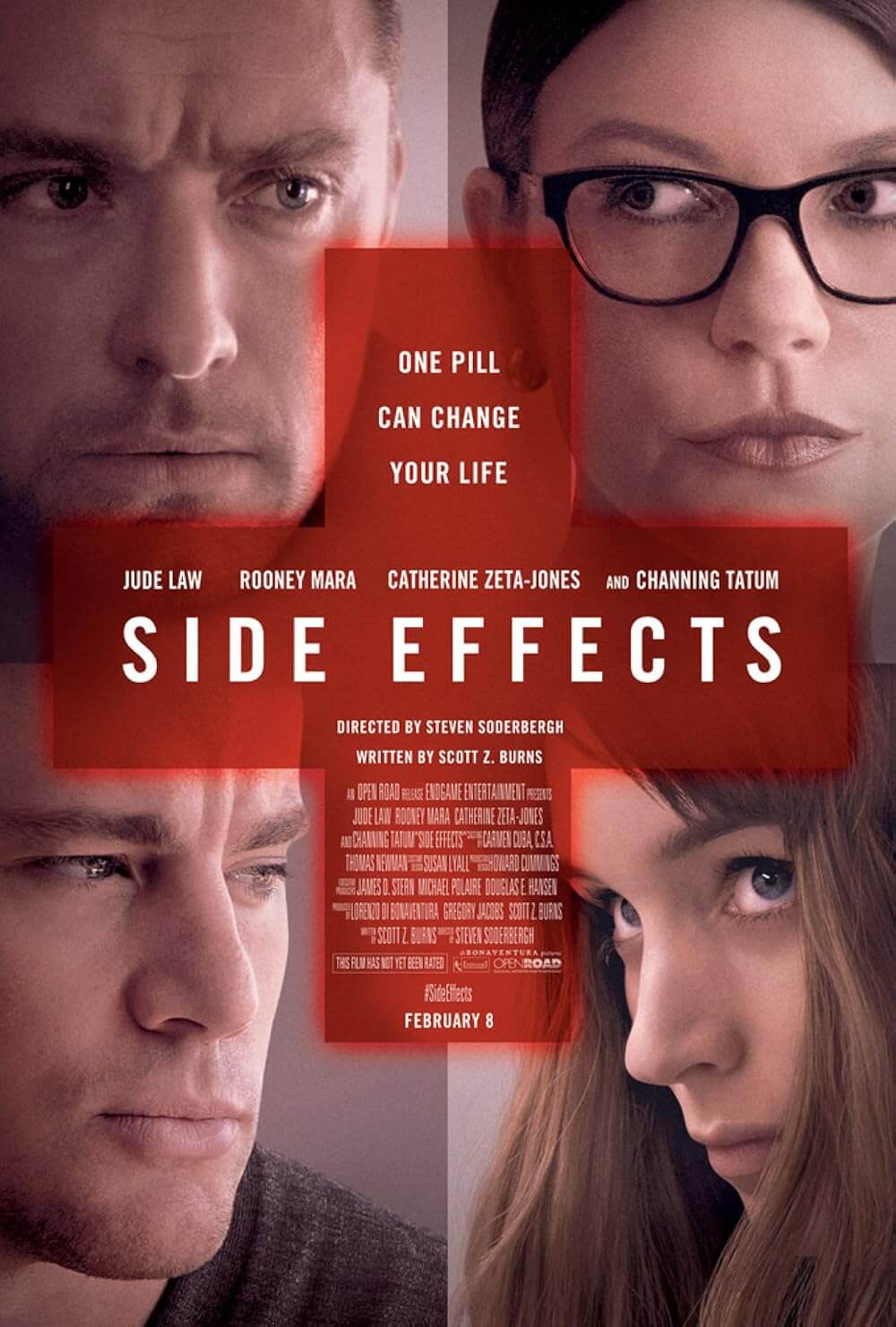

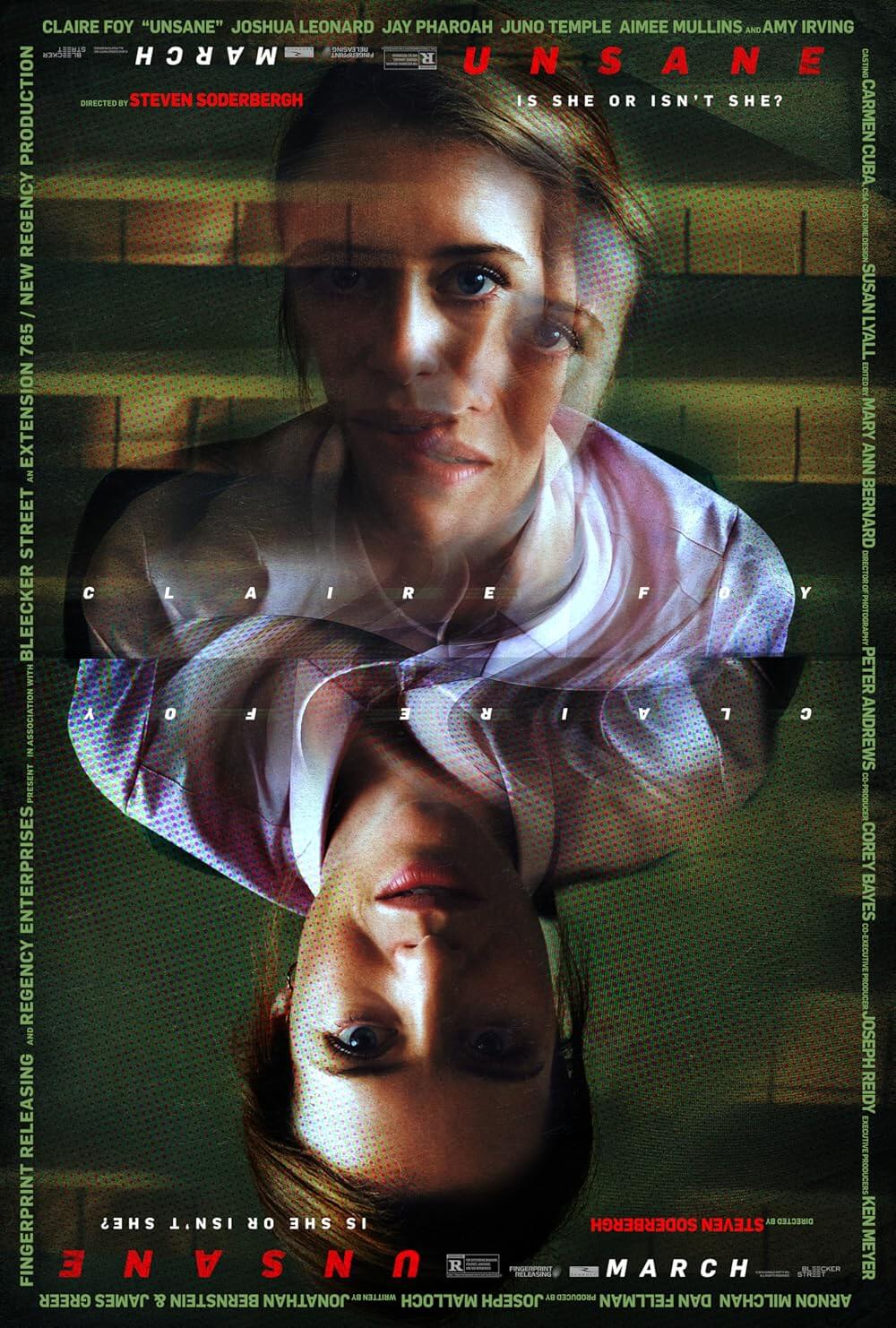

Watching Let Them All Talk, a few other titles come to mind: Olivier Assayas’ film from last year, Non-Fiction, about entangled relationships set within the publishing industry, and Deconstructing Harry (1997), Woody Allen’s comedy about a writer who borrows unscrupulously from his own life, would round out a trilogy of similarly themed films that dwell on artistic responsibility when mining personal drama for literary gold. Soderbergh’s style has more in common with the former. He sits back with a quiet and unobtrusive approach, keeping his crew and technology to a minimum. Wiest told Entertainment Weekly that Soderbergh scuttled around the ship with his camera using a wheelchair—he once again uses his alias, Peter Andrews, to serve as the cinematographer, and his other alias, Mary Ann Bernard, as editor. Every year or so, Soderbergh does this sort of one-person operation. He shot Unsane (2018) and High Flying Bird (2019) using iPhones, and before that, he helped pioneer digitally recorded and digitally distributed films with Bubble (2005).

Debuting on HBOMax, Soderbergh’s work here is best appreciated for how it compiles a series of individual moments, captured with the spirit of Robert Altman and Mike Nichols. It’s shot with class and respect for the actors, allowing each character to live and breathe, and using restrained visuals that support the scene at hand. Certain aspects about Let Them All Talk as a whole prove disappointing, especially the final few minutes of screentime, in which Tyler draws on his memories of the crossing to find some sort of meaning. A more ambiguous conclusion would have been preferred. That ending’s bow-tying montage aside, Soderbergh’s aesthetic delivers crisp images and an actor’s showcase. Using an experimental process, he offers characters whose fates remain open-ended and uncertain. Let Them All Talk could feel like a meaningless trifle to a cynical viewer; it could also feel like it has answers to the questions of life. Soderbergh gives his audience both options, while as a filmmaker, he continues the enduring struggle between commercial cinema and artistic ambition.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review