Reader's Choice

Les misérables

By Brian Eggert |

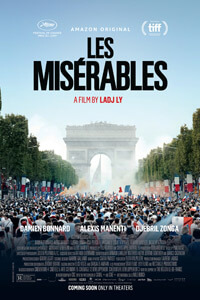

Les misérables, Ladj Ly’s first feature-length narrative film, does not attempt yet another adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 19th century novel of the same name. It does, however, take place in the same poor Paris suburb of Montfermeil, the neighborhood of Hugo’s novel that, even today, still houses a multicultural powderkeg of crime, police aggression, and social unrest. With almost documentary attention paid to harsh living conditions and sidewalks teeming with energy, Ly’s expansion of his 2017 short draws from his first-hand experiences during the 2005 French riots. He’s a somewhat controversial filmmaker whose two-year prison sentence for his role in a kidnapping, along with his convictions for earlier offenses, have been widely spotlighted by many news outlets. But threads of Ly’s past life, such as his arrest for posting a candid video of police online in 2011, work their way into the screenplay for Les misérables. Writing alongside Giordano Gederlini and Alexis Manenti, Ly’s authorship only enhances the verisimilitude of this intense thriller, whose sustained immediacy leads to an open-ended discussion prompt.

Far from the high dramatics that follow a stolen loaf of bread in Hugo’s tome, Ly’s film adopts the structure of a police procedural set in the downtrodden banlieues outside of Paris. Given the subject matter and setting, other critics have made comparisons between Les misérables and Mathieu Kassovitz’s La haine (1995) or Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989). To be sure, those influences inhabit Ly’s portrait of everyday life on the street, how he frames his narrative within a contained 24-hour period, and how the tensions between his characters gradually reach a dramatic tipping point. The ambiguous ending, too, raises questions about where the viewer should place their allegiances. Les misérables observes how cultural groups remain divided by race and religion; at the same time, the local police assume the worst about everyone, viewing themselves as cowboys in the lawless Wild West. Given the specifics of the story, however, there’s also a dash of Antoine Fuqua’s corrupt police drama Training Day (2001) and, even more so, Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995) driving the film.

Despite the national pride that Ly shows over the opening credits as Parisians celebrate France’s 2018 World Cup championship, the director reveals the divisions among them as the story progresses. Our entry point into Montfermeil is Stéphane (Damien Bonnard), a country cop who has joined the Street Crime Unit (SCU) to be closer to his ex-wife and son. It’s Stéphane’s first day in the big city, and he’s teamed with his commander, Chris (Alexis Manenti), a reactive racist who demands allegiance above all else. Chris (who actually shouts “I am the law!” at one point, and not as an ironic reference to Judge Dredd) takes pride in his nickname as the “Pink Pig” and gets his kicks by frisking teenage girls. He’s a ball of toxic masculinity and moral bankruptcy, and he has no time for Stéphane’s voice of reason. Chris’ longtime partner, Gwada (Djibril Zonga), a black man who’s slightly more sensitive, follows the leader. The two have given Stéphane the nickname “Greaser,” to which he quietly protests in his polite way.

Their day consists of patrolling dilapidated high-rises and markets overseen by Montfermeil’s Mayor (Steve Tientcheu). But their trouble begins when they search for a Muslim boy named Issa (Issa Perica), who has stolen a lion cub from Gypsy circus performers, resulting in a confrontation between the tattooed, axe-wielding Gypsies and the Mayor’s posse. When they finally corner Issa and attempt to question him about the cub, the heated bust earns a response from local children who crowd the squad. Gwanda shoots Issa with a flash ball in the chaos, a shocking act that another boy, Buzz (Al-Hassan Ly), captures on video from an overhead drone. Similar to Strange Days, the film becomes a race for the police to find the damning video before it’s made public and causes a riot. Meanwhile, Stéphane questions the implications of suppressing what he knows is wrong, even as he continues to ride with Chris and Gwanda. After seemingly resolving the conflict, returning the cub, and giving everyone a night to sleep on what has happened, Ly explores a contrived and unresolved fourth act that feels somewhat polemical in its quotation of Hugo’s original text.

Their day consists of patrolling dilapidated high-rises and markets overseen by Montfermeil’s Mayor (Steve Tientcheu). But their trouble begins when they search for a Muslim boy named Issa (Issa Perica), who has stolen a lion cub from Gypsy circus performers, resulting in a confrontation between the tattooed, axe-wielding Gypsies and the Mayor’s posse. When they finally corner Issa and attempt to question him about the cub, the heated bust earns a response from local children who crowd the squad. Gwanda shoots Issa with a flash ball in the chaos, a shocking act that another boy, Buzz (Al-Hassan Ly), captures on video from an overhead drone. Similar to Strange Days, the film becomes a race for the police to find the damning video before it’s made public and causes a riot. Meanwhile, Stéphane questions the implications of suppressing what he knows is wrong, even as he continues to ride with Chris and Gwanda. After seemingly resolving the conflict, returning the cub, and giving everyone a night to sleep on what has happened, Ly explores a contrived and unresolved fourth act that feels somewhat polemical in its quotation of Hugo’s original text.

Visually, Julien Poupard’s sharp cinematography looks almost too polished for this sort of urgent storytelling. For once, a gritty David Ayer style might have served the film better, even though Les misérables is unquestionably beautiful. Moments in the first scenes, where crowds of Parisians cheer on the French team, have been artfully framed against the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe. As fans scream into the camera, the familiar journalistic point-of-view from within the crowd also bears a greater commentary about France’s passion. The country maintains a rich history of enacting change through protest and anger, as its citizens are known to pour into the streets out of national pride and moral outrage. Ly’s approach can feel like he’s creating a portrait of France itself. Still, the director captures his scenes using cold drone photography or slick ground-level shots, which immerse the viewer in extended takes that feel less impassioned than self-conscious. Even the handheld shots, or the chaotic stairwell sequence in the finale, have an undue composure that might betray the film’s otherwise grounded story.

Similar to Jacques Audiard’s Palme d’Or winner Dheepan from 2015, Ly’s film asks France to confront how their country forces immigrants into suburbs like Montfermeil, where they struggle to improve their lives amid rampant crime and under constant oppression from local anti-crime units. As the opened-ended last shot suggests, Les misérables does not point the blame at a single party; rather, it implies that both sides are responsible for people resorting to their worst selves. The situation will continue to perpetuate itself as long as the conditions remain the same. It’s a stirring message, which Ly has contained in a national framework of historical, literary, and cinematic parallels. But unlike La haine or Do the Right Thing, Ly’s film fades to black before its story comes to any kind of satisfying conclusion. It’s a tactic that incites the viewer to think about how the director’s approach relates to real-world issues, even as it robs Les misérables of any dramatic closure. However appropriate this choice may be to create change, it leaves something to be desired as storytelling.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review