Reader's Choice

Léolo

By Brian Eggert |

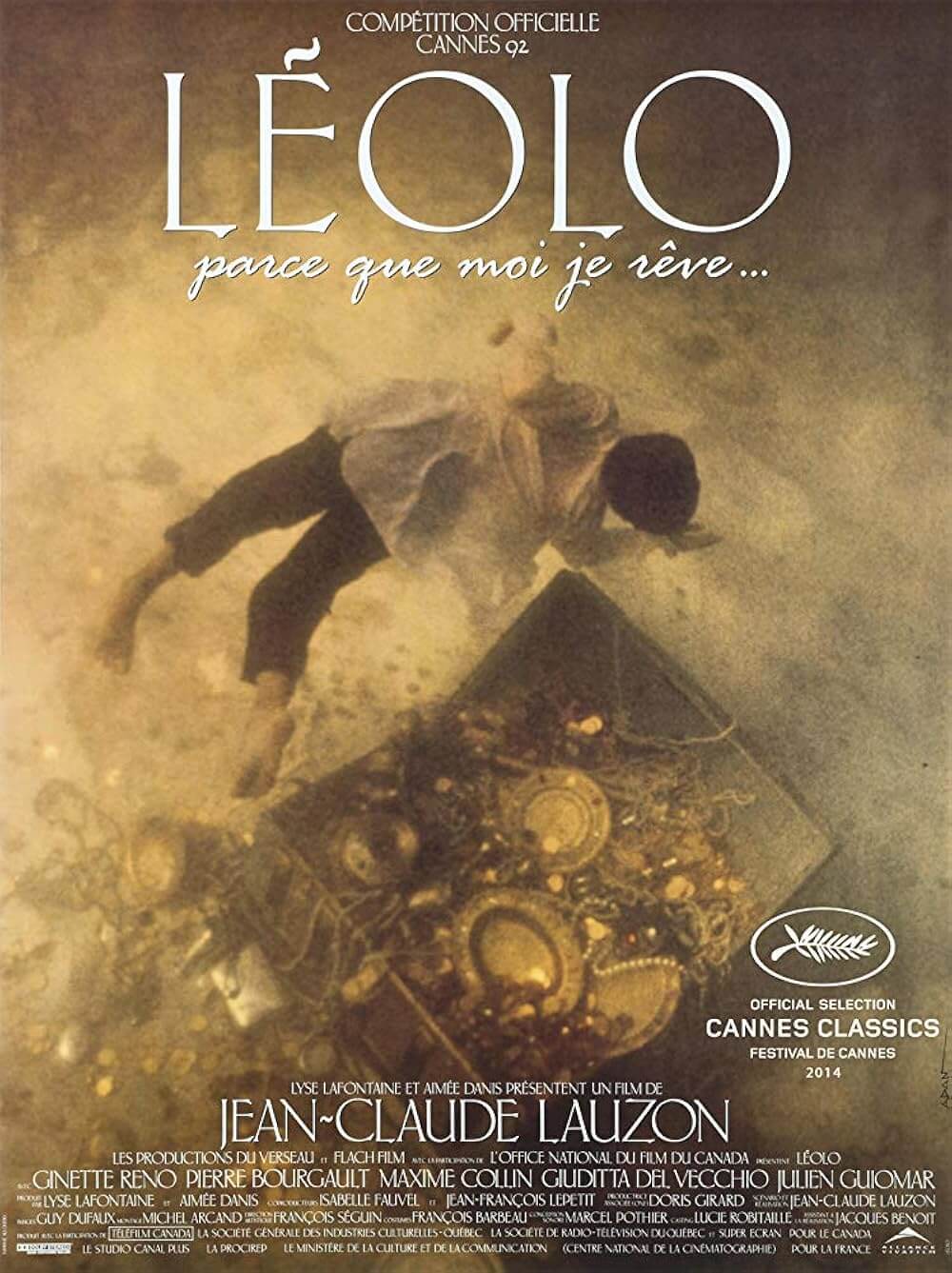

During the opening credits of Léolo, the second feature by Canadian director Jean-Claude Lauzon, white titles appear on a black screen. Amid the titles, a single image fades in: an artistic cabinet of curiosities that frames a life-sized version of Michelangelo’s David next to a hideously faced winged gargoyle that might adorn the exterior of a European cathedral. Then the image fades away, and the credits resume, not to be seen again until the film’s final moments, juxtaposing classically high art against the grotesque sculpture. Why does Lauzon interrupt the otherwise plain credits sequence with this image? Perhaps the two sculptures symbolize the blend of artistic idealism and the base naturalism found in his film’s characters—a notion further captured in the multi-tonal harmonies of chanting Tibetan throat-singers that reverberates over the sequence. Léolo is a film of simultaneous artistic tones. It is a grotesque fantasy, violating the traditional forms of good taste in its depictions of adolescent sexual discovery, scatology, bestiality, and other debauched behavior. Yet, every degrading sight in Lauzon’s film is balanced with the filmmaker’s tenderness and honesty, resulting in a strangely affecting and personal work of grotesque art.

Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin saw the grotesque as a mode of representation that mocks traditional and polite forms of art while also accepting the socially stigmatized realities about the body. In Rabelais and His World from 1968, Bakhtin’s study of Renaissance-era writer François Rabelais, the author discusses the grotesque as anything bound to offend bourgeois society, bodily processes in particular. Grotesque art often deploys deviant representations designed as an affront to classical and idealized forms. The earliest grotesque images feature monstrous figures found on the margins of illuminated books or hidden away on an architectural façade, perverse sketches passed amid the underclasses, or paintings of peasants in the throes of bodily delight—all signaling a farcical streak of vulgarity. The grotesque thumbs its nose at acceptable culture and functions in low and abject spaces. But all of these offenses to official morality employ a political agenda, aiming at stifling forms of the establishment to uncover a realism that may appear unsettling to the usual spectators. After all, human experience is not limited to traditional beauty; humanity is often a disgusting and unpleasant physical reality, and grotesque realism acknowledges this.

Léolo contains elements of both classical beauty and the grotesque. On the surface, the story’s logline could be compared to many other coming-of-age films—from Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) to Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)—following a child who escapes their hostile environment through the force of their imagination. However, Lauzon’s film has a more literary structure with no more tangible substance than memory. It floats from one episode to the next, one debauched reverie to another. It subsists between reality and the subconscious and, therefore, cannot be easily summarized beyond a description of individual scenes and images that stay with the viewer. Its perverse and disturbing incidents may make you recoil, but they also come from the writer-director’s personal experiences growing up. To whatever degree the film’s situations cause you to feel disgusted or offended, they have been infused with compassion and feelings that read as genuine. In a curious blend of gentle remembrance and stifling desperation, Léolo is a film that captures childhood in all its ugly and uncertain glory.

The film is about a dreamer in the Mile End neighborhood of Montreal. In the first scenes, the 12-year-old Léo Lozeau journals, explaining that “people who trust only their own truth call me Léo Lozeau. Because I dream, I am not.” This last phrase becomes Léo’s refrain, repeated throughout the film as a way of distancing himself from his untenable everyday life. And so, Léo remains committed to his fictional Italian, rather than actual Québécois, heritage. This stems from his obsession with an older Italian girl named Bianca (Giuditta Del Vecchio), combined with his sense of isolation in his family. He even dreams up a tawdry rationale for his origins: Somewhere on an Italian farm, a worker masturbated onto a crate of tomatoes while ogling a woman. Those tomatoes, shipped to a Montreal marketplace, softened the landing of Léo’s mother (Ginette Reno), who stumbled and fell so hard on the produce that a soiled tomato lodged itself inside her. Nine months later, Léo was born. Given his imagined parentage, Léo demands to be called “Léolo Lezoné,” a more Italian-sounding moniker. Anything to escape his family members, who suffer from an array of mental disorders that have landed most of them in and out of psychiatric institutions.

The film is about a dreamer in the Mile End neighborhood of Montreal. In the first scenes, the 12-year-old Léo Lozeau journals, explaining that “people who trust only their own truth call me Léo Lozeau. Because I dream, I am not.” This last phrase becomes Léo’s refrain, repeated throughout the film as a way of distancing himself from his untenable everyday life. And so, Léo remains committed to his fictional Italian, rather than actual Québécois, heritage. This stems from his obsession with an older Italian girl named Bianca (Giuditta Del Vecchio), combined with his sense of isolation in his family. He even dreams up a tawdry rationale for his origins: Somewhere on an Italian farm, a worker masturbated onto a crate of tomatoes while ogling a woman. Those tomatoes, shipped to a Montreal marketplace, softened the landing of Léo’s mother (Ginette Reno), who stumbled and fell so hard on the produce that a soiled tomato lodged itself inside her. Nine months later, Léo was born. Given his imagined parentage, Léo demands to be called “Léolo Lezoné,” a more Italian-sounding moniker. Anything to escape his family members, who suffer from an array of mental disorders that have landed most of them in and out of psychiatric institutions.

What begins as a quirky portrait of an offbeat family quickly descends into crude and disturbing details. Consider Léolo’s father (Roland Blouin), a factory worker and eating machine who believed, “Good health came through shitting”—to the extent that he inspected every family member’s bowel movements. This prompts Léolo to barter with his sister, dubbed Queen Rita (Geneviève Samson), for some fecal matter in exchange for a jar of bugs. Elsewhere, Léolo blames his mentally deranged grandfather (Julien Guiomar) on his father’s side for infecting the family with madness (Léolo remains unaffected, he rationalizes, because his father is the Italian masturbator and his mother is sane). Léolo’s hatred for his grandfather might have something to do with the old man paying the topless Bianca to carry out his morbid fetish of clipping his toenails with her teeth while he bathes—a sight that leaves Léolo “divided between my desire to vomit and to jack off.” Perhaps most tragic in the family is Léolo’s dim brother Ferdinand, who, after being bullied, transforms his body into a hulking mass of muscle (played by bodybuilder Yves Montmarquette). Even so, the flexing Ferdinand cowers when his bully confronts him.

Léolo copes with his family by isolating them from his reality. “My family had become characters in a fiction,” Léolo says in his voiceover, “and I spoke of them as if they were strangers.” Through his introduction to literature, Léolo can escape what he calls “the abyss of my family” by thinking of them as fictionalized characters. Literature first comes to him when a mysterious man known as Word Tamer (Pierre Bourgault), who collects the art and literature spied in the opening image, leaves a copy of L’avalée des avalés by Réjean Ducharme in their house under the leg of a wobbly table. Léolo takes the book and reads by the light of his household refrigerator. From then on, he’s bitten by the need to log his uncommonly eloquent poetic observations in a journal, which the Word Tamer reads from some distant time and place, cataloging Léolo’s words alongside the masters. The film unfolds in a series of observations and confessions from the mind of an afflicted child.

Like his main character, Lauzon had a tumultuous upbringing, and most of his family members suffered from some form of mental illness and faced institutionalization. He even dabbled in crime before escaping into filmmaking. However, Andre Petrowski, who headed the National Film Board’s French-language film division, helped steer Lauzon into a film life. The director based the Word Tamer on his real-life mentor and thanked Petrowski by dedicating Léolo to him. The film represents one of two features by Lauzon, who died in a plane crash in 1997 at 43. After making short films at university and directing television commercials in Quebec, Lauzon made his feature debut with Night Zoo, which premiered as a Directors Fortnight selection at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. The film earned him 13 Canadian Genie Awards and many other accolades on the festival circuit. Lauzon continued shooting commercials in Montreal between feature productions, occupying his time with hunting and fishing in northern Quebec, where the plane he was piloting would crash.

Like his main character, Lauzon had a tumultuous upbringing, and most of his family members suffered from some form of mental illness and faced institutionalization. He even dabbled in crime before escaping into filmmaking. However, Andre Petrowski, who headed the National Film Board’s French-language film division, helped steer Lauzon into a film life. The director based the Word Tamer on his real-life mentor and thanked Petrowski by dedicating Léolo to him. The film represents one of two features by Lauzon, who died in a plane crash in 1997 at 43. After making short films at university and directing television commercials in Quebec, Lauzon made his feature debut with Night Zoo, which premiered as a Directors Fortnight selection at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. The film earned him 13 Canadian Genie Awards and many other accolades on the festival circuit. Lauzon continued shooting commercials in Montreal between feature productions, occupying his time with hunting and fishing in northern Quebec, where the plane he was piloting would crash.

Lauzon took his time to develop his second feature, Léolo, which would become his last, most widely praised and most personal of his two films. However, personality issues may have prevented him from making additional films. In his review, Roger Ebert describes Lauzon as “long-haired, outspoken, a little wild, ready to offend or take offense.” Ebert also shares a story about Lauzon propositioning juror Jamie Lee Curtis at Cannes, single-handedly ruining the director’s chance to take home the Palme d’Or. Even so, just before his death, Lauzon had struck a deal with the Toronto-based Alliance Communication Corp. to make his first English-language feature. One can only speculate what Lauzon would have made, given the rare combination of precious metals and crude material found in Léolo. Indeed, the closest cinematic companion to Lauzon’s visual style and willingness to place a child into such unsettling circumstances is Terry Gilliam’s hard-to-sit-through Tideland (2007). That film, about a young girl who lives with the corpse of her overdosed father and escapes into a fantasy world, might even prove less accessible than Lauzon’s. But both share touches of magical realism combined with merciless reality, though their magic proves black as pitch.

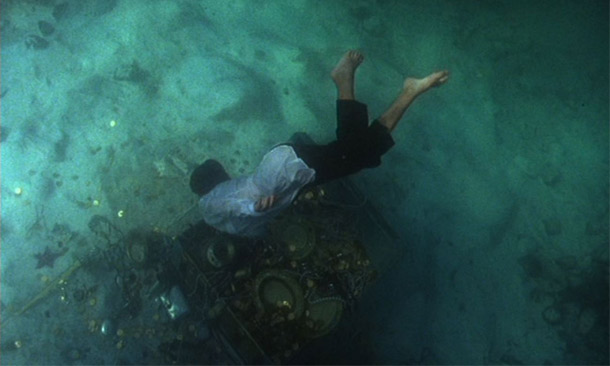

Take when Léolo accidentally splashes his grandfather from an inflatable pool, and the patriarch responds by attempting to drown the boy. At that moment, Léolo loses himself in an adventurous undersea dive for treasure, a gorgeously photographed escape from a near-murder. Léolo’s imagination might be called Felliniesque, carrying him away into some momentary scene like the main character in 8 ½ (1968). Cinematographer Guy Dufaux captures richly textured images of idyllic cityscapes and daydreams. One recurring image shows Léolo on the windowsill, scribbling in his journal and struck by the white light of his pure fantasies about Bianca. But such reveries are countered with considerable screentime in the putrid family bathroom, complete with a live rat and turkey in the bathtub. Among the most depraved sequences involves the young boy discovering his sexuality with a nudie magazine and then using a piece of liver to pleasure himself—only later to watch, horrified, as his family consumes the liver for dinner (a possible reference to Phillip Roth’s 1969 novel Portnoy’s Complaint). And I haven’t even mentioned the cat rape sequence, but perhaps that’s for the best.

Amid all the film’s self-abasement and often nauseating behavior from Léolo’s family, his refrain echoes like the Tibetan chants on the soundtrack: “Because I dream, I am not.” Michel Arcand’s editing and Dufaux’s gentle camera movements defy the grotesque images, counteracting them with a sense of reverence that inhabits Léolo’s desire to escape into another world. But whenever the film absorbs the viewer into a serene passage, Lauzon breaks that dream with an unseemly chunk of reality. Also underneath the grotesque portrayal is odd humor, accented by the beatnik sounds of Tom Waits’ “Temptation” and “Cold Cold Ground” against the familiar and ironic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” by The Rolling Stones on the soundtrack. These flourishes alternate with the multiphonic singing that turns the film into a transcendent religious experience. Like every aspect of the film, from form to content to sonic tones, Lauzon juggles the high and low.

Amid all the film’s self-abasement and often nauseating behavior from Léolo’s family, his refrain echoes like the Tibetan chants on the soundtrack: “Because I dream, I am not.” Michel Arcand’s editing and Dufaux’s gentle camera movements defy the grotesque images, counteracting them with a sense of reverence that inhabits Léolo’s desire to escape into another world. But whenever the film absorbs the viewer into a serene passage, Lauzon breaks that dream with an unseemly chunk of reality. Also underneath the grotesque portrayal is odd humor, accented by the beatnik sounds of Tom Waits’ “Temptation” and “Cold Cold Ground” against the familiar and ironic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” by The Rolling Stones on the soundtrack. These flourishes alternate with the multiphonic singing that turns the film into a transcendent religious experience. Like every aspect of the film, from form to content to sonic tones, Lauzon juggles the high and low.

Just a few years after its release, Léolo earned a place on Richard Schickel’s 2005 list of the 100 best films ever made in Time magazine. In his 2005 “Great Movies” entry prompted by Schickel’s list, Ebert warned that Léolo “is in danger of being misplaced.” That’s true enough today. This is a difficult film to see, even in a world of countless streaming services and physical media labels. At the time of this review, it cannot be streamed online or purchased in the United States (my viewing consisted of a subpar, out-of-print DVD released 20 years ago and bought from an online marketplace). Still, the power of Lauzon’s vision and emotional immediacy came through the pixelated presentation, even as his bracing honesty caused me to cringe with revulsion. Everything Léolo experiences, he imagines taking place in a fictional, even cinematic world, and Lauzon brought that world to life—a creative act that amounts to a rare example of intensely personal filmmaking. Although it’s bound to incite disgust and loathing, there’s an unadulterated honesty and imagination here that makes Léolo uncommon and cherishable.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Themistoklis!)

Bibliography:

Ebert, Roger. “A boy who’s saved by his dreams.” RogerEbert.com, 31 July 2005. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-leolo-1993. Accessed 14 April 2022.

Leach, Jim. “It takes monsters to do things like that: The films of Jean-Claude Lauzon.” Great Canadian Film Directors. The University of Alberta Press, 2007.

Racine, Claude. “Jean-Claude Lauzon.” The Young, the Restless, and the Dead: Interviews with Canadian Filmmakers. Vol. 1. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2008.

Toles, George. “Drowning for Love: Jean-Claude Lauzon’s Léolo.” Canada’s Best Features: Critical Essays on 15 Canadian Films. Rodopi, 2002.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review