Leaves of Grass

By Brian Eggert |

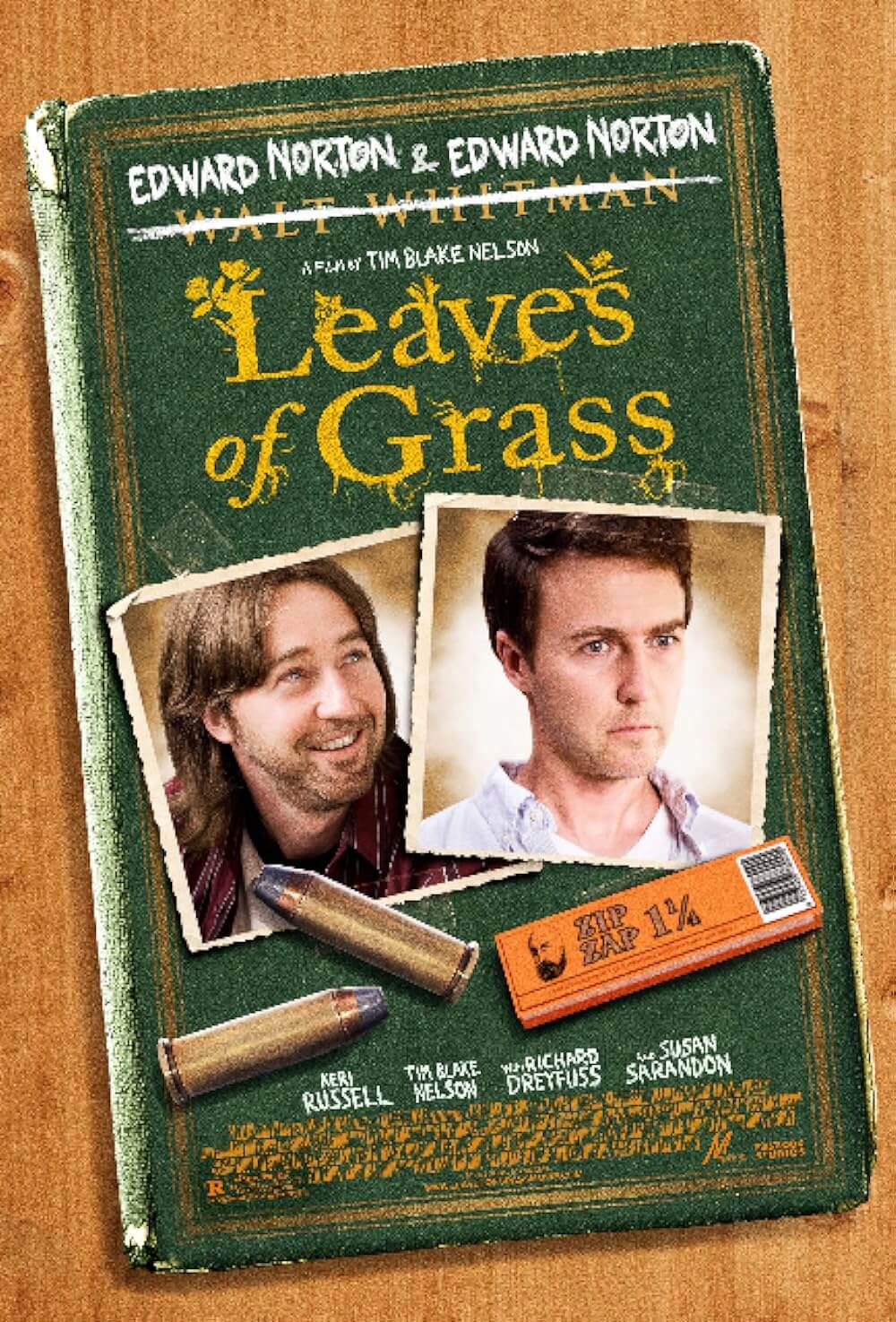

Drawing influence from his work with the Coen Brothers, writer-director Tim Blake Nelson’s latest, Leaves of Grass, contains similar shifts in tone, quirky humor, and sudden, stark violence—attributes that pull the viewer this way or that. To offset what initially (and falsely) appears to be an unbalanced pitch, Nelson incorporates grand philosophical ideas influenced by serious writers ranging from Plato to Walt Whitman, to keep the synapses in the viewer’s brain clicking away. At the center of this odd mix of low-brow and high-brow are two ingenious performances by Edward Norton, playing identical twins, in one of the most impressive turns in the actor’s career. On the whole, Nelson’s efforts were apparently too smart, or too odd, for the major studios, so the film, unfortunately, makes its debut on home video, where it will hopefully grow into a savored hit.

Tricked into leaving his intellectual sanctuary in Rhode Island and returning to his less academic hometown in Oklahoma, Ivy League philosophy professor Bill Kincaid (Norton) learns that his identical twin brother, Brady (also Norton), is not dead as he was told. Rather, Brady has tricked Bill to return home, because he needs his brother to make an appearance and provide him with an alibi. Brady, you see, sells marijuana that he’s engineered through an elaborate, self-designed hydroponics system, and in doing so he’s gotten into trouble with a local crimelord. And though Bill proudly flouts his scholarly prowess as a teacher of classical philosophy, both brothers are intelligent, simply in different ways. Brady’s deep brogue and scruffy appearance give way to more casual mannerisms, whereas Bill has constrained himself to a strict discipline of the mind. Both fields have their merits but on their own lack emotional stability.

While the supporting cast—including Keri Russell as a cat-fishing poet and Richard Dreyfuss as a staple of his Jewish community (who finances pot dealers on the side)—proves interesting, the viewer remains bewildered by the incredible performances by Norton. Comparable to Jeremy Irons’s dual role in David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers or Nicolas Cage’s roles in Adaptation, Norton creates two fully formed personalities. They prove to be more defined than two bodies and one soul, but also less divergent than polar opposites. Norton realizes Bill and Brady as brothers, alike in their ways, but distant as brothers can sometimes be. His portrayals are so natural that while watching, we can’t help but forget this is the same actor. He allows us to forget about Nelson’s special effect of placing two Edward Nortons in one shot, so instead we plunge into the story. And if it weren’t for the film’s truncated debut on home video, Norton might be a lock for a Best Actor Oscar nomination.

Most will write off the title as a mere marijuana reference (certainly the minor marketing campaign and DVD cover seek to exploit this plot detail), but there’s a deeper, more resonant meaning that Nelson hopes to achieve. Leaves of Grass is also the name of Walt Whitman’s collection of poetry, originally published in 1855, which itself makes a brief appearance in the final shot to punctuate the reference. Whitman’s transcendentalist works find equal importance in both the mind and body and Nelson brings those ideas to fruition through Bill (the intellectual) and Brady (the live-in-the-moment pot smoker). Despite his penchant to play dim-witted characters with his heavy southern drawl, Nelson is an intellectual whose collegiate career boasts time at both Brown University and Julliard. His script is filled with external representations of poetic concepts and should not be overlooked as a wacky, post-Fargo yarn about small-time crooks and schemes-gone-wrong.

Rather, just as the layered title suggests, there’s something clever behind the picture that engages both the intellectual viewer and the viewer searching for raw entertainment value. Nelson’s body of work grows more complex with each new film. From the movie version of his play Eye of God to the sobering tale of Auschwitz with The Grey Zone, also based on his play, Nelson shows an incredible capacity for thoughtful dramas. And, as evident with Leaves of Grass, he knows how to incorporate scholarly concepts into a mainstream comedy. If only a major studio would have taken the risk to distribute his smart little film. In fact, given the draw of Norton and the appeal of the pot-based plot to younger viewers, it’s any wonder why this wasn’t picked up. Alas, the film’s tours on the festival circuit have only earned it a wide distribution on home video, where most independent films wind up these days. Now it’s up to you, responsible moviegoer, to seek this film out and spread the word.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review