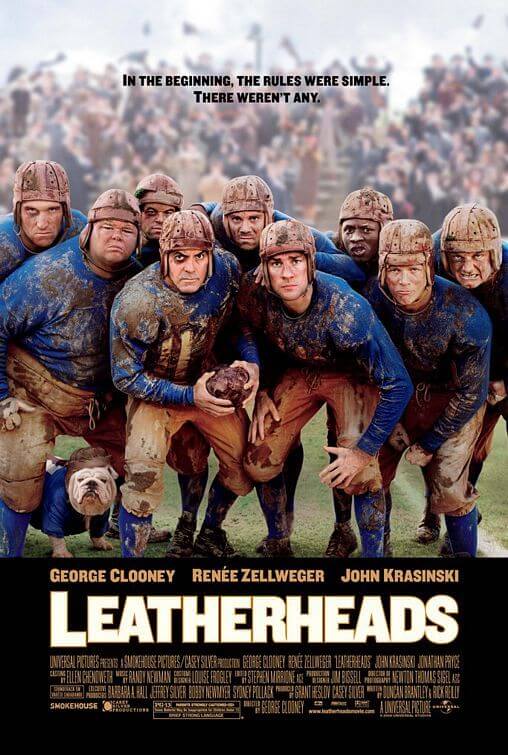

Leatherheads

By Brian Eggert |

The degree to which Leatherheads, George Clooney’s most recent and tremendously enjoyable foray into acting and directing, exists as a screwball comedy demands consideration. His film has elements of the much-missed genre from the 1930s and 1940s, using the crackerjack dialogue and snappy witticisms purveyed by icons such as Howard Hawks and Preston Sturges. But his film also centers on the grim early pro-football scene, and how the transition of going from middle-of-nowhere field matches to big-buck stadium events tapers the fun inherent in the game. Remarkably, Clooney creates a balance between farce and his commentary on football politics, delivering a pleasant throwback.

The film opens circa 1925, where Clooney stars as Dodge Connelly, an aged pro-football star who can’t, nor does he want to do anything else. This is before the NFL, before big-time advertisers, and before paychecks were in the millions. Though college football remains all the rage, professional players could barely earn enough to survive, much less rely on getting paid. But their love of the game keeps them coming back; they love having their heads mashed into the mud with a staggering lack of safety by way of protective padding. They relish every minute. Teams even forfeit because they don’t have the budget to keep playing.

Meanwhile, pseudo-Sergeant York, WWI hero, and college football star Carter “The Bullet” Rutherford (John Krasinski) has his celebrated face on everything from razors to cigarettes thanks to his seedy agent CC Frazier (Jonathan Pryce, from Brazil). Rutherford’s growing stardom sells out college games by the thousands, leaving Connelly with the potential to jumpstart pro football’s dying organization. Except, just how heroic is this Rutherford that the American people love so dearly? The inquiring mind of sharp-tongued reporter Lexie Littleton (Renée Zellweger) wants to know. She sets out to find the truth behind Rutherford’s exaggerated claims of battlefield heroism, naturally falling for him in the process. Meanwhile, Littleton butts heads with Connelly, since she seeks to expose his cash cow. Their conflict peaks with punchy dialogue, resolving in, of course, an endearing cute device that brings the two together.

All the actors fit wonderfully into their roles, but I am now questioning which version of George Clooney I enjoy more: Clooney the Director or Clooney the Actor. As director, his now three pictures (including Confessions of a Dangerous Mind and Good Night, and Good Luck) that labor over the details, with evident and impressive control over the cinematic apparatus and period mise-en-scène. Partnering with The Coen Brothers and Steven Soderbergh on nearly ten pictures between them, something’s obviously rubbed off on Clooney. And it’s his work in front of the camera for those filmmakers (O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Solaris, Out of Sight) that has established Clooney as one of the few movie stars today who still dazzles like icons Humphrey Bogart and Cary Grant used to (and, indeed, still do).

The production design on Leatherheads, overseen by James D. Bissell, the same designer behind Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck, captures the essence of the 1920s—or at least, Hollywood’s image of the Roaring Twenties. Noted songwriter Randy Newman handles the music, which kept my foot tapping with early jazzy hits. Writing credit goes to Duncan Brantley and Rick Reilly, but according to reports, Clooney rewrote a good portion of their script; when the WGA refused to give him onscreen credit for his rewrite, the star promptly dropped out of the guild. And Clooney’s uncredited writing captures his playful genre exchanges with plush era-specific terminologies, Hawksian dialogue, and cartoonish slapstick. In one scene, Connelly and Rutherford engage in fisticuffs, delivering more facial wallops than I could count. Later, neither wear bruises to show for it—not because of deficient continuity, but rather because Clooney’s production follows the rulebook established in the Golden Age of cinema, where a punch in the face doesn’t leave a mark, cause swelling, or induce blood flow.

The film’s only fault may be its tone, which shifts considerably from hearty screwball sports comedy in the beginning to a slowly dwindling infusion of reality—the reality that the freeborn temperament of early football was eventually washed away when the sport entered the big leagues. No more “crusty Bobs” or other such rough-n-tough schemes, later called “cheating,” to get you through the game. Admittedly, football looks like it would be more enjoyable if the teams could pull a fast one. The lighthearted spirit returns in the finale, where Clooney brings us back to the blithe style that captured us in the first place. Instead of just employing one genre as vintage Hollywood might, Leatherheads confronts how the game’s ideals were crushed by the bureaucracy of politics and thus addresses those highs and lows accordingly. Maybe that approach doesn’t sustain the viewer’s high throughout the picture, but it’s genuine and heartfelt and keeps us from relying on safe genre tropes.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review