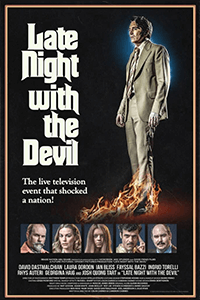

Late Night with the Devil

By Brian Eggert |

Late Night with the Devil has a terrific premise rooted in a faux-documentary style. It opens with Michael Ironside’s expository narration about a fictional late-night variety show. In the 1970s, Jack Delroy hosted Night Owls, a struggling talk show in the shadow of giants such as The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. On Delroy’s Halloween 1977 broadcast during Sweeps Week, a notorious night of television “shocked a nation,” propelled by Delroy’s alleged cultist ties; his wife, who had died of lung cancer the year before; and the first rumblings of the Satanic Panic that spread throughout America at the time. Written and directed by siblings Colin and Cameron Cairnes, the format of the movie switches to found footage, where the ensuing 90 minutes consist of the episode’s master tapes, along with some rare behind-the-scenes footage cut into the mix. While effectively freaky and well-acted, the slow-burning tension builds to a disappointing finish, marred by the filmmakers’ loose commitment to the found footage format. Still, it’s easy to admire for its convincing visual sense and theme of selling one’s soul for fame.

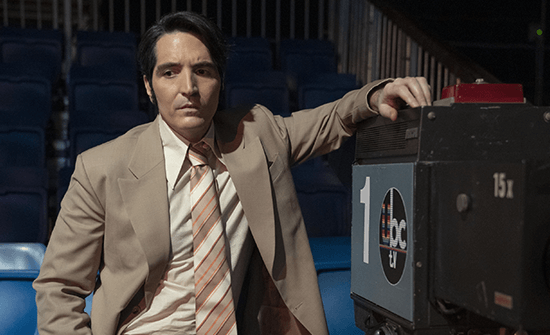

David Dastmalchian is excellent as Jack Delroy. You may have seen him as a creepy character in movies such as Prisoners (2013) and Boston Strangler (2023). But here, the actor transitions from dark-eyed weirdo to chummy talk show host effortlessly, delivering one of his best performances. The movie unfolds as though you’re watching an episode of Night Owls, complete with the host’s comic monologue, banter with his co-host Gus (Rhys Auteri), and “after these messages” cuts to commercial breaks. The guest lineup evokes familiar faces from TV in the ’70s, though with an intended Halloween flair. First, the psychic medium named Christou (Fayssal Bazzi) engages the studio audience to communicate with the spirits of their deceased loved ones. But then Carmichael the Conjurer (Ian Bliss), a former magician turned skeptic, arrives to expose Christou’s routine, recalling the tension between real-life illusionist Uri Gellar and famous debunker “The Amazing” James Randi, who often appeared on The Tonight Show and panel shows. Except, uncanny details in Christou’s performance emerge, suggesting something genuinely wicked looms in the studio.

Delroy frets to his producer (Josh Quong Tart) backstage between segments, worrying about whether the show will be sensational enough to earn the ratings needed to keep Night Owls afloat. There’s a mild desperation to Delroy that neutralizes his wounded, sympathetic widower persona. It emerges gradually, such as when his next guest, Dr. June Ross-Mitchell (Laura Gordon), a parapsychologist with whom he’s vaguely romantic, brings out Lilly (Ingrid Torelli). The young girl is surely based on Michelle Smith, the inspiration for Michelle Remembers, the discredited 1980 book in which Smith and her psychiatrist supposedly uncover repressed memories from her time as a Satanic cult victim. Delroy practically drools over the potential ratings after he convinces Lilly’s reluctant doctor to conduct an on-air interview with the demonic spirit inhabiting the child, who likes the attention and cameras on her. But Delroy is playing with fire, and Carmichael continues to hostilely question the validity of the situation. There’s plenty of disturbing imagery to follow, with Torelli doing a fine interpretation of the possessed Linda Blair.

When a movie enters the found footage arena, it subjects the storytelling and formal execution to added scrutiny beyond that of a typical horror movie. Not only must it tell a good story and supply the requisite scares, but it should raise other questions: How well do the filmmakers adhere to their narrative conceit? Do they work within the limitations established by the story, or does the aesthetic play outside of those boundaries? A good one will never break from the visual logic of the story, supplying an immersive experience that seldom tests the viewer’s suspension of disbelief. Every edit should be justified by what’s happening onscreen; every visual source should be accounted for within the story. When done right, a found footage movie will seem like a snuff film, something we’re not supposed to see. Creep (2014) and Quarantine (2008) execute this almost flawlessly. Admittedly, it’s a critical pet peeve when found footage movies don’t follow their established rules; it feels as though the filmmakers cheated at their own game and thus hoodwinked the viewer. Examples of this are wide-ranging, though most installments of the ongoing V/H/S anthology series usually feature one or two entries that betray found footage logic.

When a movie enters the found footage arena, it subjects the storytelling and formal execution to added scrutiny beyond that of a typical horror movie. Not only must it tell a good story and supply the requisite scares, but it should raise other questions: How well do the filmmakers adhere to their narrative conceit? Do they work within the limitations established by the story, or does the aesthetic play outside of those boundaries? A good one will never break from the visual logic of the story, supplying an immersive experience that seldom tests the viewer’s suspension of disbelief. Every edit should be justified by what’s happening onscreen; every visual source should be accounted for within the story. When done right, a found footage movie will seem like a snuff film, something we’re not supposed to see. Creep (2014) and Quarantine (2008) execute this almost flawlessly. Admittedly, it’s a critical pet peeve when found footage movies don’t follow their established rules; it feels as though the filmmakers cheated at their own game and thus hoodwinked the viewer. Examples of this are wide-ranging, though most installments of the ongoing V/H/S anthology series usually feature one or two entries that betray found footage logic.

Late Night with the Devil is a mess from this perspective. Although the prologue’s narrator suggests that what we’re about to see consists of footage from the live broadcast intercut with never-before-seen backstage footage, the aesthetic choices convey this without a rigid formal agenda. The most convincing footage entails the live broadcast, captured in a boxy aspect ratio, with fuzzy lensing, which is standard for the period’s TV shows. Cinematographer Matthew Temple and the directors, who also edited the film, replicate the long zooms and studio camera switches customary for the ’70s. However, the backstage scenes, shot in black-and-white and presented in widescreen, don’t blend well with the setup; they deploy two-shot editing and cover intimate moments that not even a documentary crew could have captured—nor is such a crew established, begging the question: Who shot this footage? There’s no diegetic reason for these shots to exist, so they are not found footage. Similarly, the finale seems to exist in a wholly different plane, breaking from what the narrator claimed in the opening. It’s a pesky betrayal of form-follows-function principles.

Most of the acting and novelty of the basic setup sustain Late Night with the Devil. And the Cairnes execute the movie with such skill for most of the production that you can’t help but admire the outcome. However, after the stated found footage agenda is established, the viewer notices how the filmmakers deviate from that path, like an essay that argues its thesis poorly. Moreover, the production’s use of AI to create some of the Halloween-themed “We’ll Be Right Back” transitional cards has also brought the film’s integrity into question. By the time the hodgepodge ending comes along, complete with outlandish CGI that feels like an anachronism given the ‘70s-ness of everything onscreen, the movie abandons the mode almost entirely. Even so, it’s a breakthrough role for Dastmalchian, who handles the quick-witted comebacks and talk show host charm like a pro, hopefully signaling to The Powers That Be in Hollywood that he’s capable of much more than supporting roles as misfits and maniacs. And if the inconsistencies of found footage logic aren’t likely to bother you, then you may find Late Night with the Devil to be a creative and inspired entry in the horror genre.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review