Last Night in Soho

By Brian Eggert |

Although 1960s nostalgia peaked in the 1990s, it’s alive and well in Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho. Then again, perhaps “alive” and “well” aren’t the correct adjectives in this context. “Dead” and “exploited” may be more apt. Nostalgia becomes a nightmare haunted by ghosts and a knife-wielding slasher in the film, which marks several firsts for Wright: it’s his first film to feature a female lead, his first time directing a narrative film not steeped in comic ironies, and his first where his deliriously entertaining formal choices support the story rather than frame it. Since his cultish horror-comedy debut Shaun of the Dead (2004), Wright has explored stories that situate a bromance within an established genre. Buddy cops, comic books, alien invaders, and heists have dominated his output, always accented by humor and zippy camerawork that has cemented his devoted fanbase. With his latest, Wright contributes to a recent wave of Nuovo Giallo pictures, including James Wan’s Malignant, that draw stylistic influence from Italian masters like Dario Argento, Mario Bava, and Lucio Fulci. That decidedly masculine and usually exploitative style receives a makeover thanks to Wright’s update, which places a woman at the center and makes the grim reality of exploitation a central theme. It’s a refreshing modernization that balances style and substance, whereas traditional Giallo films often rest on style alone.

The script by Wright and Krysty Wilson-Cairns follows Ellie, an aspiring fashion designer obsessed with the culture of ‘60s London. Played by Thomasin McKenzie (Leave No Trace, 2018), Ellie is waifish and dreamlike. She looks as though she spends a lot of time in her head—a furtive place that harbors fantasies about the past and possibly some extrasensory abilities. The film hints that she might see the dead; then again, she might have the same mental illness that drove her mother to suicide. As Ellie sets off from her small town in Cornwall to fashion school in London, her supportive grandmother (Rita Tushingham) warns that the big city might cause her to “get all overwhelmed again.” The implication raises doubts about our protagonist and whether her eventual self-described “visions” are actual glimpses into the past or hallucinations brought about by schizophrenia. When she arrives in her dorm and meets her catty and unwelcoming roommate (Synnøve Karlsen), Ellie quickly realizes that her affection for The Searchers and Dusty Springfield over Billie Eilish or Lorde will make her an outsider. And so, she resolves to leave the dorm and rent a room from a kindly older woman (Diana Rigg). Conveniently enough, the space hasn’t been redecorated since the ’60s, allowing Ellie to lose herself in the past.

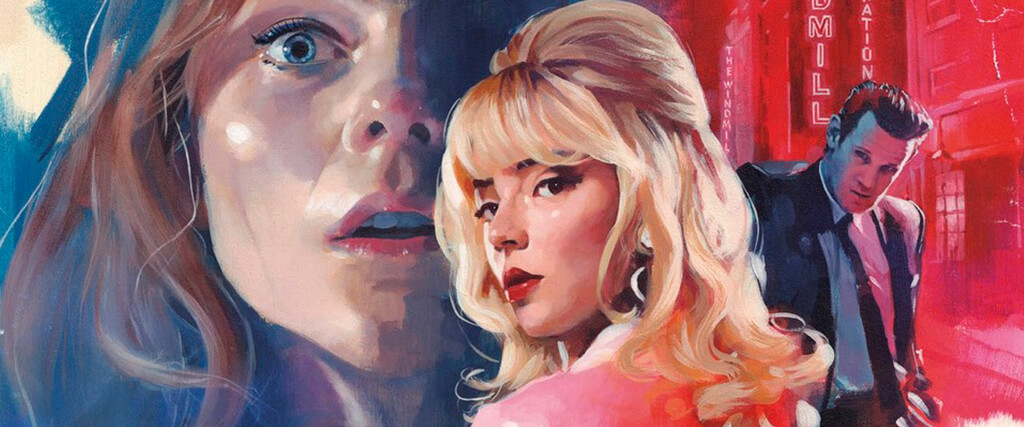

Instead, the past haunts Ellie. When she sleeps at night, she enters a vivid dream—a mental portal to Soho some 60 years earlier. There, she sees through the eyes of a confident and beautiful young woman named Sandie (Anya Taylor-Joy), who, like Ellie, arrives in London set on stardom. Overwhelmed by the surface details of her dream, Ellie watches as Sandie meets the debonair Jack (Matt Smith), who romances her and agrees to be her manager as she starts her singing career. The following day, Ellie finds her fashion school designs inspired by Sandie’s appearance; she even buys herself some vintage couture and changes her hairstyle to look like Sandie. After that, she starts living for nostalgia, setting aside interactions with real people in favor of returning to her ’60s dreams at night. And while Last Night in Soho opens by romanticizing the past as Ellie does, it doesn’t take long for Wright to shift the setting to a terrifying and twisted place by revealing Jack’s motives. Sandie will be the latest addition to his stable of young women whom he puts into a burlesque show and pimps out to businessmen. “We all have to start somewhere,” he rationalizes cruelly. With Ellie following as a silent observer, Sandie walks backstage and sees women strung out, debauched, and exploited. The nightly journeys into a ’60s fantasyland that Ellie cherished quickly become a nightmare she wants to escape.

In the ‘60s, Soho was known for its clubs, music, miniskirts, and a seedy underbelly, most of which have been replaced by posh restaurants and shops. Production designer Marcus Rowland and costumer Odile Dicks-Mireaux capture the vintage style in all its glory of floral patterns, bold colors, and boogie-woogie attitude. But Ellie’s fascination with so-called Swinging London remains limited to its superficial products of pop music and fashion, while her knowledge about the setting’s everyday reality proves limited. Wright uncovers the real Soho during its heyday, a place where men treated women like meat on the slab, and the women were chewed up and then forgotten. Sure, the location produced a wealth of iconic looks and sounds. But along the way, there was untold human collateral, exploited by the era’s attitude of fun-loving liberation that regularly fed predators like Jack and his clientele. Trapped in this world alongside Sandie, Ellie’s nighttime dreamscape becomes a trap—and the boundaries between sleep and consciousness, fantasy and reality, and life and death blur in disturbing ways, destabilizing her school work and preventing a relationship with a fellow student (Michael Ajao).

In the ‘60s, Soho was known for its clubs, music, miniskirts, and a seedy underbelly, most of which have been replaced by posh restaurants and shops. Production designer Marcus Rowland and costumer Odile Dicks-Mireaux capture the vintage style in all its glory of floral patterns, bold colors, and boogie-woogie attitude. But Ellie’s fascination with so-called Swinging London remains limited to its superficial products of pop music and fashion, while her knowledge about the setting’s everyday reality proves limited. Wright uncovers the real Soho during its heyday, a place where men treated women like meat on the slab, and the women were chewed up and then forgotten. Sure, the location produced a wealth of iconic looks and sounds. But along the way, there was untold human collateral, exploited by the era’s attitude of fun-loving liberation that regularly fed predators like Jack and his clientele. Trapped in this world alongside Sandie, Ellie’s nighttime dreamscape becomes a trap—and the boundaries between sleep and consciousness, fantasy and reality, and life and death blur in disturbing ways, destabilizing her school work and preventing a relationship with a fellow student (Michael Ajao).

The whole film operates like a haunted house, if the house existed only in the past or Ellie’s mind. In a way, Last Night in Soho has much in common with The Shining (1980): They both follow a character cursed with a strange ability to see a traumatic past through apparitions. Both protagonists face real and supernatural threats. Ellie believes that Jack murdered Sandie and, tormented by flashes of murder and sexual exploitation, she tries to acquire proof that Jack is still alive and passing as a local perv nicknamed “Handsy” (Terrence Stamp, intimidating beyond measure). The film’s last third contains a bit too much of Ellie running frantically from CGI shadow figures, be it Jack or semi-transparent predatory shadow men who reach out for her around every corner. The imagery becomes almost overwhelming and certainly not as assuredly handled as the first two-thirds—that is, until a pair of compelling twists and turns near the end bring the themes together.

Wright aims his usual bravado at the singular goal of serving the story; however, the film isn’t without countless veiled references to its antecedents. For starters, there’s the inspired casting of ’60s icons such as Stamp, Rigg, and Tushingham (the latter two making their final appearances onscreen). Elsewhere, every major sequence contains a subtle wink to Giallo predecessors. Take the alternating blue, white, and red light that fills Ellie’s room from a flashing French bistro sign: it’s both Wright’s homage to films like Argento’s Suspiria (1977) and Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981), but the switching of colors also becomes an editing prompt to switch the image to jarring effect. Wright’s euphoric visuals pop off the screen, gleaming with primary colors, reflective streets, and startling violence—all captured with luster by cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung, best known for his work with director Park Chan-wook (The Handmaiden, 2016). But he also employs audio and visual distortions, implying the breakdown of Ellie’s fantasy and even her mind. The distortions and fast cutting threaten to destabilize the finale, but Wright brings the viewer to the brink and not beyond it.

Wright’s output could be accused of going overboard. He starts well and builds confidently, but his climaxes usually feel like he’s reaching for too much, especially in The World’s End (2013) and Baby Driver (2017). Last Night in Soho has an ambitious final act that isn’t as slick and stylish as what came before. Yet, it’s thematically and emotionally satisfying thanks to McKenzie’s committed performance and our investment in Ellie. Moreover, the film boasts a million sensory pleasures from Wright’s evident fascination with the cinema and music that inspired him. His needle drops turn cheery songs into harbingers of death in this context, such as James Ray’s “Got My Mind Set on You” and Sandie Shaw’s “(There’s) Always Something There to Remind Me,” among many others. Besides using many of Shaw’s songs on the soundtrack, Wright also borrows from her biography as a small-town girl who broke into the ’60s London music and fashion scene, albeit with better results than the film’s Sandie. Best of all, Wright does what many Giallo films tried to, only he roots the central character in believable emotions and leaves out the streak of exploitation that often made the originals feel cheap. By the end, Last Night in Soho reminds us that behind cultural products reside the people who created them. If recent history has taught us anything, sometimes those people are victims, predators, or both.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review