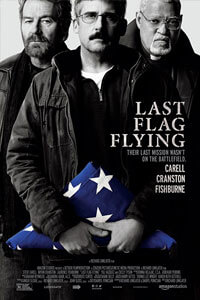

Last Flag Flying

By Brian Eggert |

Last Flag Flying has the laid back style of writer-director Richard Linklater’s great hangout films. From his independent debut on Slacker (1990) to his monumental Before trilogy (starring Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy in what are ostensibly three film-long conversations), his characters debate and listen, while Linklater observes, and the audience remains enrapt. Although his films could be accused of having a dull or unassuming visual sense—aside from his rotoscoped philosophical wonder Waking Life (2001) and superb Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly (2006), both animated—his casual style enhances the meaning behind his films. Last Flag Flying contains arguments and memories, laughter and a welling of tears. It feels like a long and epic journey, though the plot could be summed up in a sentence or two. The filmmaker concentrates on his characters and their relationships, while inevitable political commentaries remain secondary. Perhaps most of all, the film is a showcase for three excellent performances by Steve Carell, Bryan Cranston, and Laurence Fishburne.

At the same time, the film bears a bewildering extratexual continuity that puts a distance between itself and its various sources. Linklater based his screenplay on the 2004 novel by Darryl Ponicsan, a sequel to the author’s 1970 novel The Last Detail. Hal Ashby directed an adaptation of The Last Detail in 1973 starring Jack Nicholson, Randy Quaid, and Otis Young, a countercultural classic. But Linklater isn’t making a sequel to Ashby’s film, nor is he entirely faithful to Ponicsan’s novel. The characters’ names and timelines have been changed around, leaving any hope of coherence between these various sources somewhat perplexing. Call the result a “spiritual sequel,” whatever that means. Set in 2003, the film reflects on a time when much of the U.S. believed the invasion of Iraq would surely yield weapons of mass destruction, Saddam Hussein had just been captured, and many had begun to notice the disheartening parallels between Vietnam and the Middle East conflicts.

Three Vietnam veterans—Sal Nealon (Cranston) and Richard Mueller (Fishburne) were Marines, Larry “Doc” Shepherd (Carell) was a sailor—get together for the first time in thirty years to reflect on their memories, and also create some new ones. In the opening scene, the shy, slouching Doc enters a bar in Norfolk, Virginia, owned and operated by Sal. A hedonist and foul-mouthed drinker, Sal welcomes his old friend, oblivious to the pain behind his eyes. After a night of sad boozing, Doc invites Sal to visit their pal Richard, a former addict who is now long-reformed and married, with two adult children, and serving as a pious and stuffy reverend. Doc informs his former friends that his wife died of breast cancer nearly a year ago, while their only son, a Marine, was recently killed in Iraq. Now alone, Doc asks his former military buddies to help him bury his son. Sal remains ever ready to try something new, while Richard cannot ignore the bad influence these men once had on his life. Urged to carry out the mission by his wife as the Christian thing to do, Richard joins the trio that travels by car, moving truck, and train in a familiar road movie plot.

The screenplay by Linklater and Ponicsan gradually reveals information about its characters, recasting their bond over the course of the film’s two-hour runtime. Vague references to the events in Ponicsan’s novel of The Last Detail suggest a sordid past between the three. Sal and Richard evidently made a decision (a theft in the 1973 film, something more involved here) that led to Doc spending two years in the brig, followed by a bad-conduct discharge—it’s a “better career decision,” Doc jokes, since the mark on his record meant his career was limited to serving as a clerk in a Navy supply store. Sal and Richard carry a sense of regretful obligation to Doc, but also a natural friendship. When they arrive at the hangar to claim the body of Doc’s son, Doc resolves not to bury him at Arlington National Cemetery, but rather, at his home of Portsmouth, New Hampshire—much to the objection of a bureaucratic colonel (Yul Vazquez). Doc is certain in his decision given the disparity between the official story of the boy’s death, which involves a heroic firefight and ambush, to the real story shared by a fellow Marine (J. Quinton Johnson), involving a senseless death. Indeed, Last Flag Flying contains an unmistakable cynicism toward governments, authorities, and official statements; and yet, it remains romantic about the way Marine life has shaped these men.

The screenplay by Linklater and Ponicsan gradually reveals information about its characters, recasting their bond over the course of the film’s two-hour runtime. Vague references to the events in Ponicsan’s novel of The Last Detail suggest a sordid past between the three. Sal and Richard evidently made a decision (a theft in the 1973 film, something more involved here) that led to Doc spending two years in the brig, followed by a bad-conduct discharge—it’s a “better career decision,” Doc jokes, since the mark on his record meant his career was limited to serving as a clerk in a Navy supply store. Sal and Richard carry a sense of regretful obligation to Doc, but also a natural friendship. When they arrive at the hangar to claim the body of Doc’s son, Doc resolves not to bury him at Arlington National Cemetery, but rather, at his home of Portsmouth, New Hampshire—much to the objection of a bureaucratic colonel (Yul Vazquez). Doc is certain in his decision given the disparity between the official story of the boy’s death, which involves a heroic firefight and ambush, to the real story shared by a fellow Marine (J. Quinton Johnson), involving a senseless death. Indeed, Last Flag Flying contains an unmistakable cynicism toward governments, authorities, and official statements; and yet, it remains romantic about the way Marine life has shaped these men.

To be sure, there’s no clear-cut or simple ideological perspective for these men. They believe in the military lifestyle, but they remain critical of its leadership. They also talk at length about the lies that perpetuate conflicts which require young, strong people to sacrifice themselves for their country, which they love, but not in the sentimentalized way that many people talk about soldiers. The actors handle these dimensions well thanks to the naturally flowing script, often with a tragic sense of humor. Beneath a sketchy New Yorker accent, Cranston is the show-stealer, always tapping his fingers to a tune playing in his head, his mouth jabbering on, his arms flailing about as he talks. Sal remains the funniest and the most unavoidably confrontational of the group, and Cranston, though his performance feels more suited for the stage, is excellent. Carell and Fishburne offer more internal performances, the former playing a familiar kind of wounded innocent, while the latter stews with a righteousness that occasionally gives way to booming regressions into past behavior.

As the plot meanders, the film’s loose narrative structure unfolds, and the cumulative weight of the performances and their discussions begins to take hold, despite ungainly deviations. An unfortunate aside finds Sal pressuring the others into a joint cell phone plan. Because the film takes place in 2003, the ubiquity of smartphones has not yet saturated the world, and the nostalgia for simpler times feels like a misguided comic device. Even so, there are many lovely, hilarious, and tender moments in Last Flag Flying. However confusing its sequel status (or not) may be, the film maintains Linklater’s modest style and perceptive view into his characters, while also exploring what war does to everyday human beings. The cast demonstrates their talents in a variety of scenes and moods, and the low-key tone offers surprising emotional heft. The film ends up feeling at once simple and complicated, preachy and rambling. But like it’s characters, the film’s downtrodden and funerary proceedings don’t prevent the audience from laughing through the otherwise serious, tearful material.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review